- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

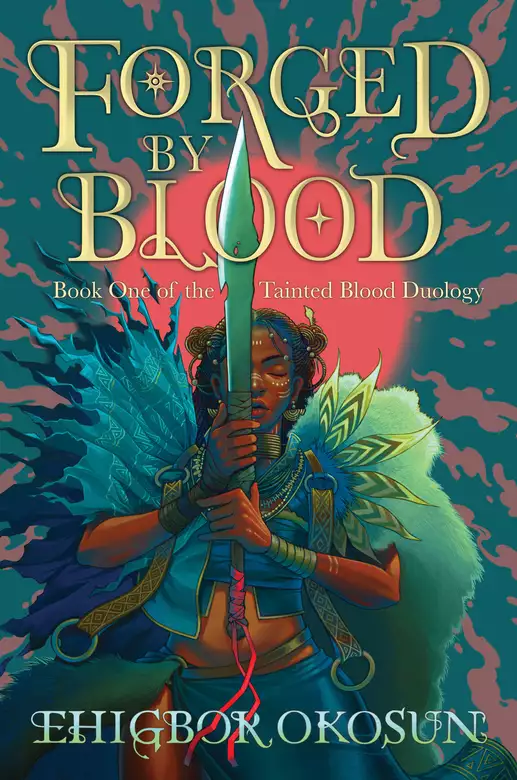

The first book in an action-packed, poignant duology inspired by Nigerian mythology

Dèmi just wants to survive: to avoid the suspicion of the nonmagical Ajes who occupy her ancestral homeland of Ife; to escape the King’s brutal genocide of her people – the darker skinned, magic wielding Oluso; and to live peacefully with her secretive mother while learning to control the terrifying blood magic that is her birthright.

But when Dèmi’s misplaced trust costs her mother’s life, survival gives way to vengeance. She bides her time until the devious Lord Ekwensi grants her the perfect opportunity – kidnap the Aje prince, Jonas, and bargain with his life to save the remaining Oluso. With the help of her reckless childhood friend Colin, Dèmi succeeds, but discovers that she and Jonas share more than deadly secrets; every moment tangles them further into a forbidden, unmistakable attraction, much to Colin’s – and Dèmi’s – distress.

The kidnapping is now a joint mission: to return to the king, help get Lord Ekwensi on the council, and bolster the voice of the Oluso in a system designed to silence them. But the way is dangerous, Dèmi’s magic is growing yet uncertain, and it’s not clear if she can trust the two men at her side.

A tale of rebellion and redemption, race and class, love and betrayal, FORGED BY BLOOD is epic fantasy at its finest, from an enthusiastic, emerging voice.

Release date: August 8, 2023

Publisher: HarperCollins

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Forged by Blood

Ehigbor Okosun

“Please heal him,” the woman says, begging Mummy with tear-filled eyes. “Please.”

My mother grunts, but she takes the boy from the woman and sets him on our cot in the corner of the room.

This woman will get us killed, I know it.

But I waddle over, dragging the calabash behind me, its heavy wooden body leaning against my legs like a cow about to give birth. When I reach the edge of the cot, I open the neck and pour palm wine into the cracked bowl lying next to it. Mummy pulls the boy’s eyelids up and peers at pale irises ringed with red cracks. Then she unbuttons his tunic and examines the network of bulging red veins spread across his pale skin.

“Dèmi?” she says.

“Okonkwo poisoning. It’s been at least six hours. He won’t last another,” I say.

She nods. “Good. How long will the recovery be?”

“If he is healed now, then at most a day. But the healer will be exhausted for three.”

She smiles, brushing a lock of my tightly coiled hair from my face, brown eyes shining with pride. Then she turns to the woman. “Even if he’s healed, your son might still pay a price in the future. Are you prepared?”

The woman’s tearful face morphs so quickly into a mask of disgust that I fear I imagined her tears. She spits on the floor—our floor—before tossing a cloth bag on the ground. Several gold coins roll out, littering the mud like the kwasho bugs that crawl around in summertime. There is at least twenty lira, enough to feed us for two years, even with the extra trade taxes.

“Pure gold,” she sneers. “More than you’ve ever seen in your miserable lives. That should be enough. Or do you need more?”

I bristle. “Gold will not stop the spirits—”

Mummy shoots me a glance and I swallow my words. She straightens her back. We only have the small kerosene lantern to light our hut, but her skin—brown like fresh kola nuts—glows golden in that light. Her braided hair is a crown adorning her heart-shaped face. For a moment, I see her again as she used to be, before she was cast out, a princess of Ifé.

“Healing is a balance. Life for life. Your boy ingested a lot of poison. I can only ask the spirits for mercy. What they do is up to them,” she says, giving the woman a frosty look.

“You mean—you mean he might still die,” the woman says, her creamy face growing paler.

“Mummy is the best healer in all Oyo,” I say proudly. “She won’t let him die.”

The woman shrinks from my gaze, busying herself with loose threads on the waistline of her silk dress, arrogance driven away by fear. Turning back to Mummy, I hold out the cracked bowl without a word. I know what she would say, why she didn’t bother responding: just because we don’t understand others doesn’t mean they deserve our ridicule or hatred.

Never mind that we’re the only ones required to live by such a rule.

Mummy tilts the boy’s head up and pours the palm wine into his mouth. He gurgles feebly but drinks it all. She lays him back down, and I fetch the palm oil and salt from the cupboard. There are only a few drops left in a jar of palm oil that was supposed to last six months. Too many healing rituals.

Harmattan season is upon us, and its dry, sandy winds drive children into the forests like a traveling musician draws crowds. The Aziza come during Harmattan, guiding hunters through the thick underbrush, flying from tree to tree. One child they choose will have a wish granted, so even with the prevalence of okonkwo bushes near Aziza tree houses, children flock to them all the same.

I would, too, if I didn’t know better. Even the magic of the Aziza cannot call back the dead.

Mummy dips a finger in the oil and marks the boy’s face. For softness, to ease his journey in the Spirit Realm. Then she dabs some salt on his tongue. To remind him of the taste of human life. I stretch a hand over his chest, but she shakes her head.

“You will wear out. I don’t need half as much rest,” I insist.

“It’s too risky. My abilities are known, but yours—”

“What’s happening over there?” the woman asks, voice rising to a shriek. “What are you saying?”

I realize now that Mummy and I have slipped into our native tongue, Yoruba, a relic of the past kingdom outlawed in public.

“She’s preparing for the ritual,” I say quickly in Ceorn, offering the woman an apologetic smile. “She wants to make sure everything goes well.”

The woman narrows her eyes. “If anything happens to him, I’ll make sure you rot in meascan prison, where you belong.”

I draw in a breath, feeling as though I’ve been slapped.

You should be first to die, then, for letting your child fall ill in the first place.

I want to scream in her face. The woman spits again, and it takes everything I have to hold myself still. Meascan. Adalu. It’s times like these, when these insults wash over me, that I drown in a well of anger. There are so many words for what we are, words sung over me like a lullaby of curses since my birth. The message is the same: We are not human. We are tainted. Tools to be used and discarded.

It never changes, this ugly dance. This woman no doubt came here for the winter festival—perhaps to meet a friend she hadn’t seen

in many moons, or even a lover. Wealthy Eingardians like her flock to Oyo like crows settling on a corpse. Celebrations here are cheaper; the people willing to bow when they see a light-skinned face; they are ready to worship, and Eingardians crave worship. When they run into trouble, they look to Mummy and me. They’re willing to pay so dearly for illegal magical help, from curing boils to saving an infected leg. But after, when it’s time for drinking and dancing, they remind us we will never sit at the same table—we are deadwood, cut down for the fire that warms their cold hearts and hateful faces, whittled into the benches they sit on. They beat us, insult us, and expect us to keep serving without complaint.

So Mummy and I make bitter leaf pastes for blemishes and pain, draw fever from hot skin, and exhaustion from weary bones. And when the soldiers come, purple-and-gold tunics flecked with traces of dried blood and iron swords like mirrors reflecting our terror, our patrons will be long gone, their needs met. It will be just Mummy and me then, trading coin for the privilege of survival, until the next rush.

Gathering the abandoned coins, I shove them at the woman. “Take it.”

She backs away. “I’ve already paid. Don’t go back on your word,” she says, but her bottom lip quivers as she speaks, fearing we might do exactly that.

“Leave it, Dèmi. It’s time,” Mummy says.

I whirl around. “But she—”

“What have I taught you? Èrù jé ògá àjèjì. Ó si leso aláìmòkan èdá di ehànà.”

Fear is a strange master. It makes monsters from the simplest of men. “But Mummy,” I say, “she can’t just—”

Mummy whispers, “You’ve heard it all before. Let it go.”

Shamed, I stand aside. I want to complain, to tell my mother that I, too, am afraid. The money is heavy in my hands, but I choke back a sob. This is the weight we must carry in order to live. The way the trades were going, we were due to run out of money at the end of the season. Our humanity means nothing if we are dead. As I spy the triumphant look on the woman’s face, however, I wonder if my pride is too high a price to pay.

Mummy’s attention is only for the sick boy before us, my tattered pride forgotten. She splays her fingers on the boy’s chest and closes her eyes. “Blessed Olorun, Father of Spirits and Skies, please help your child find his way back home. Larada. Heal.”

In a moment, her eyes turn from brown to amber, and white flame erupts from her fingers, consuming the boy. The woman cries out, but her voice sounds so far away. I watch as the fire eats the veins

protruding from the boy’s fair skin. Once the last sign of red is gone, the fire slims to smoke, dancing into the air until it disappears. With a loud gasp, the boy sits up, shaking like a leaf caught in the wind. His eyes are frenzied, as though he has woken from a bad dream.

Mummy strokes his back. “You’re safe. Just lie back and rest.”

He coughs weakly, leaning against her hand. “Did I die? I dreamt that I was elsewhere. A place where people’s faces kept changing.”

“You nearly did,” I say, letting anger seep into my voice. “I don’t know what you went into the forest for, but was it worth your life?”

The boy’s gaze locks onto me, his eyes the blue of early dawn, sharp with flecks of gold sky woven through, and for a moment I am caught, watching the day bloom before me. He turns his head and I let go of the breath I didn’t know I’d been holding. Here in Ikolé, many of us are the same, with skin like coconuts and honey, and eyes like burnt sugar. But because of the trades Mummy and I make in the market and the winter festival celebrations, I have seen a variety of colored eyes; green in the smiling merchants who come from the south, dark gray and deep blues in the cold-faced northern tourists. Mama Aladé, my mother’s best friend, even has eyes that resemble the swirling purple-pink of twilight, but all that is nothing like the richness I find in this boy’s face.

He shoves his hand in the pocket of his trousers and pulls it out again, offering me his closed fist. I take a step back, instantly on my guard before his fingers open to reveal a small blue flower with crumpled leaves and a patch of yellow in the center. I gasp, reaching for it before I can stop myself. Violets like these grow deep in the forest, in groves that only creatures like the Aziza and the tree spirits know of. They are rare treasures native to our Oyo region, not found in the frosty Eingardian northern mountains or the lush Berréan southern plains. Eingardian ladies covet them so much that the sale of this flower alone would feed us for five years. How did this boy get his hands on something so precious?

And then I remember he did so by risking his life.

I brush the soft petals with a finger, careful not to push too hard. The woman smacks my hand and moves in front of me, blocking him from view.

“Don’t touch him, unless you want to die,” she sneers.

Mummy pulls me to her side, taking my smarting hand in hers. “You didn’t mind us touching him a moment ago, but now that the treatment is done, it is back to the old ways, isn’t it?”

The woman stiffens, bright spots of color once again appearing on her cheeks. “I paid you. The work is done, so I’ll leave with him now.”

Mummy shakes her head. “You can’t.”

“Of course I—” the woman splutters.

“His body will be weak for a little while. Leave him here for a few hours and let him rest. When he has some strength you can take him then.”

The woman’s eyes widen with fear. “There’s no need for that. He comes with me now. I have heard stories of your kind. I know what you do to children when their mothers’ backs are turned. I—”

Whipping out the small knife hanging at her waist, Mummy slashes her palm, then offers her hand to the woman. “I make you a solemn promise that your son will not be harmed. May Olorun punish me for going back on my word.” Then she clenches her fist and holds it over her heart. Blood drips onto the blue-and-white bodice of her dress, snaking onto the swirling patterns spread throughout.

I have never heard anyone make a blood oath, but the power in those words is enough to make me afraid. The woman’s face is ashen, and she trembles before nodding her agreement. If I didn’t know better, I would think her cognizant of the old ways, in awe of the oath that will become a death sentence for my mother if it is violated. She looks back at the boy. His eyes are closed, his chest rising and falling with an even cadence. Finally, she sniffs and says, “You will lose more than your life if anything happens to him. I can swear to that. I’ll be back by eventide.” She gathers up her skirts and sweeps out of our hut.

Mummy collapses onto a nearby chair, shoulders slumped, and for a moment I wonder if the woman exhausted her more than the healing. I rush to her, clasping her bleeding palm in mine. Calling upon the threads of magic humming through me, I pour some of that fire back onto Mummy’s hand. The flesh throbs against my fingers as it knits itself back together, and when it is done, I press my cheek against her palm.

She smiles, but there are lines etched in the corners of her eyes and beads of sweat dripping onto her neck. Healing the boy has taken so much out of her, and the day has barely begun. Grabbing one of the carved bowls sitting on the table in the corner, I go to the pot hanging over the grate. When I pull off the lid, the smell of roasted pumpkin seeds and blanched greens rises into my nostrils and stirs my stomach, but I bite my lip and scrape diligently until I have enough egusi soup to fill the

bowl. Soon the charred bottom of the pot is all that remains, a black hole jeering at the pangs straining my belly, but I set the soup in front of Mummy.

She pushes it toward me. “You must be hungry by now. Eat. I still have some work to do.”

I free a block of pounded cassava from the plantain leaf it is wrapped in and push it into the soup. “You know I don’t like my eba soaked. But you do. I’m still full from the yam porridge this morning, and you didn’t have any.”

“Dèmi . . .”

I brush by her, fetch the pouch full of dried bitter leaves from the cupboard, and pour some into the mortar on the table. She keeps trying to catch my eye, but I focus on knocking the pestle into that mortar, beating until I hear the sloshing sound of Mummy’s fingers in the soup.

“I’ll bring you some bread from Papa Adawu,” she says between bites of food.

“Try and get goat meat too. We’re running out.”

She nods, licking her fingers like a cat washing itself, trying to catch every nook and cranny. Then she takes a swig of water and stands abruptly. “What would I do without my little helper?” she says, stroking my cheek.

I smile, showing off the gap in my front teeth, twin to hers. “You would be very lonely.”

She picks up the basket in the corner and balances it on top of the wrapped caftan adorning her coily hair. Pieces of fabric hang out, like fruit dangling on a tree. Bold colors, in different shapes and sizes, all in preparation for the coming winter ceremonies. I pour the coins from the bag into the ogbene tied round her waist, squashing the folds of the cloth so the coins don’t fall out. Then I draw back the thatched door to let her through. She smiles at me, sunlight glistening on her skin, both hands bracing the basket on her head. Her long fingers are worn with calluses and marks, but the basket sits on her head like a crown, and her chin, held high, separates her from the other women milling about, carrying their wares to the market.

“Look after the boy, my dear. I’ll be back soon.” She blows me a kiss, and then she is off, disappearing into the distance, like a shadow slipping into the night.

I watch until I no longer see that slender back, then secure the latch behind the door and carry the green paste from the mortar to the cot. The boy lies there, fair eyelashes kissing the skin underneath his eyes. I tug softly on his chin, trying to pull open his mouth. His eyes fly open, and I nearly drop the mortar in fright.

“I thought you

were asleep.”

He pushes with his elbows until he is sitting up. His mouth is drawn and his cheeks red when he speaks. “Sorry. I had to do that or else Edith would never leave.”

“Edith?” I raise an eyebrow. In Oyo, it’s disrespectful to call your parents by their given names. “You call your mother—”

“She’s not my mother,” he says insistently. “She’s raised me since I was little, but she’s not my mother.”

I shove the mortar under his nose. “I’m only giving you extra medicine. See? So please just take it and go to sleep. We don’t want trouble from your Edith.”

He doesn’t, though. Instead he holds out the violet. “My real mother is sick, but she likes these flowers. They only grow in this area though.”

“So?”

“So I went to the forest to get them,” he says sheepishly. “I thought . . . I thought she’d feel better if she saw these.”

He is staring at me with those sea-colored eyes, but I look away, focusing instead on the small crumpled flower in his hand. “May I?”

He nods and I scoop it gently into my palm, ignoring the tingle that races up my fingers as they brush against his skin. I focus instead on the soft, silky feeling of the petals, and immediately the wrinkled petals smoothen, the violet spreading out in my palm like a flower in bloom. I shove the violet back into his hands, but it is too late.

He grabs my wrist, eyes wide and excited. “How did you do that?”

“Do what?” I snap, wrenching my wrist out of his hold.

To my surprise, he puts the flower down and claps his hands together in a pleading gesture. “I saw it. You have magic, too, don’t you? I won’t tell anyone, I swear, so will you show it to me? Please?”

I cross my arms. “I don’t know what you’re talking about. Even if I did, why would I do that? So you could set the kingdom guards on me like your Edith threatened to do to my mother?”

He sinks back against the wall, wilting. “I’m sorry. I don’t mean to pry. I . . . I’m not like Edith. She’s afraid of magic, but I’m not.” He wrings his hands. “We don’t have magic in Eingard anymore. All the magic users in our part of the kingdom were rounded up and killed a long time ago. We grow up hearing tales of how evil magic is. But I had an uncle who was different. My mother’s brother. He used to show me all kinds of things and talk to me about magic.”

“What happened to him?”

His skin goes pale—which is saying something—and he seems a small

child hiding from the memory of a nightmare. I perch on the edge of the cot, my hand resting near his knee. He sniffles. “The king’s guard took him away.”

I shift closer now, pressing my back into the cool mud wall, feeling him trembling next to me. I remember the first time I saw someone taken away from our village. Those gold-and-purple uniforms, that serpentine insignia, the way Mummy seized up like a statue and hid me in her skirts. I can still hear that lone Oluso’s screams as they tied him to their metal poles and carried him off . . .

I stare at the boy, and he stares back, sorrow heavy in his eyes. I sigh. “You promise not to tell anyone?”

He smiles. “I don’t have anyone to tell.”

I don’t know what that means, yet Mummy’s warnings fly into my head, remembrances that I wear like the cowry shell bangles that grace my wrists: Trusting another person is like swimming in a river. You can rest in the currents, but you must be prepared for the whorls that will come, and know there’s a chance that, one day, you will crash against the rocks and drown in the raging waters.

This thought is powerful, and yet so are his eyes—so earnest—gazing at me.

I spread my arms wide. My magic against my skin. The musky, hot air in the room swirls about my fingertips, and within seconds there are glowing white spheres flying about the room. One glides to my fingertip and, touching it, I think of the violet, of flowers in full bloom littering the forest floor. The white spheres shift into flowering shapes, swimming about like lilies on the water.

He gasps, reaching for one, but the white flower floats away from him. “How?” he whispers.

“They’re wind spirits. I asked them to join us for a little while.”

I wave my hands in the air, picturing the sparkling brightness of the stars littering the night sky. All at once, the flowers shift into a shower of tiny lights, raining all around us. He jumps again, trying to catch one, but they slip through his fingers and zip around him. I watch with amusement. Before my magic first woke, I was like that, too, eager to touch the wind spirits that flitted about my mother. As though touching them would help me find the missing piece, the hidden path to my magic that lay in me all along. It is inevitable that this boy, too, feels the call, that his spirit desires to taste the magical world where it first drew breath, a world that has been sealed away from Aje like him. Seeing his beaming face awakes an ache in my chest, sorrow for the joys he will never experience, a silent mourning for the threads of his magic that were cut before he left the womb.

“How do you do all this?”

I shrug. “I don’t know. I just think of them and ask them to come. Then I think of what shape I want them to arrive in.”

“But where do they come from?” he asks excitedly. “How does the magic work?”

I raise an eyebrow. “They really didn’t teach you anything up in the north, huh?”

He lowers his eyes. “As I said, we’re told magic is evil, and unless we control people like you, you’ll use it to murder us.”

I fling myself to my feet and all at once the wind spirits fade. I am not sure if it’s the heat or my anger that burns my skin when I speak again. “Is that what you think? That Oluso are murderers?”

The boy shakes his head vigorously. “No, it’s just—”

I wave a hand and green fire bursts from my fingertips, coiling itself around his arms and legs like vines creeping along a wall. His eyes widen, but instead of the rage I expect, his expression is still that of sheer wonder. The curled lip I have grown accustomed to, the snarl people give when they find out what my mother is, is nowhere to be seen. The boy is grinning, showing off even, pearly teeth.

I feel a little quiver in my chest, but I ignore it. “I could kill you right now,” I say menacingly.

“But you won’t.” I’m about to say something, but he pushes on. “If you wanted, you and your mother could have let me die, but you saved me. I know that, and I’m profoundly grateful. I wasn’t trying to insult you, I swear. I just . . . I just wanted to let you know that I don’t know anything about”—he waves a hand around the hut, indicating both my home and my magic—“anything. So can we start again? Please?”

The confidence in his voice irks me, but my anger is already fading. I wave my hand again and the vines dissolve. He holds out his palm, offering the common greeting among friends. “I’m Jonas, from the Maven Keep of Eingard. You?”

His name tickles my tongue as I try to push it out. Yo-nas. Definitely a Northerner. I hesitate a moment, then clap my palm to his, stroking the skin of his hand with my thumb. “I’m Dèmi. This is my village.”

He smiles. “Dèmi, I like that name. Isn’t it of the old language? What does it mean?”

I shrug, shifting my attention to the abandoned mortar sitting on the corner of the bed. Perhaps it’s a good thing few people speak

Yoruba now. The collapse of the old kingdom happened nine years ago, a year before I was born, but I hear the longing in my mother’s voice every time she speaks. Mourning for the days when Ifé was strong and beautiful, for a time when the four regions lived together in relative harmony. But those days are long gone, and my name is a reminder of that. My name is a curse, and although I have pledged Jonas my friendship, this is one river I do not wish to wade in.

“I’m not sure,” I say finally. “My mother taught me some Yoruba, but since there’s a heavy penalty for speaking the old tongues . . .”

I drift off. Language is just one of the ways Alistair Sorenson, our new king, stripped us of our dignity. Being caught using any language other than Ceorn, the native language of Eingard, is deserving of public flogging and being sent to the mines.

Jonas flushes, the tips of his ears going pink. “I just thought it was cool. Your name, I mean. I’ve heard all the people in Oyo have interesting names. All the names have special meanings. My father chose my name. It was his father’s. He doesn’t know what it means, but he hopes I’ll take after my grandfather.”

“So it has meaning too.”

He shrugs. “I guess.”

“And do you?”

“Do I what?”

“Take after your grandfather?”

He smiles, but the light doesn’t reach his eyes. “In some ways, but I would rather not. He wasn’t a good person.” He clears his throat. “So . . . you never answered my question from before. How does the magic work?”

I had answered his question with “I don’t know.” So I wasn’t sure what he was getting at.

“What do you mean?”

“I mean why do some people have it but others don’t? I asked that question once in school and got punished for it.”

I lift an eyebrow. “They beat you in your Eingardian schools?”

He flushes again. “No. They inform our guardians and send us home for the day. Canings are . . . too public.”

For Oyo-born like me, punishments mean slaps, kicks, and canings. If I were to talk back to Sister Aislinn, the Eingardian missionary who runs the village school, I would be flogged in front of my classmates. Or worse, if they decided my crime was big enough, I could be sent to the blood mines or a noble Eingardian house as an indentured worker. Mama Aladé’s two eldest children were taken last year, for participating

in a sit-down protest when the raids began. When we saw her son Tolu two moons ago, after a year in the mines, he had permanent scars and could not be out in the sun after being kept in the dark all the time. Mama Aladé’s daughter, Wunmi, came back from one of the Eingardian keeps missing two of her fingers, most of her teeth, and sporting a swollen belly.

But I do not want to think of that now. To see Wunmi with her heavy eyes that drip tears all day long and the belly that pulses and dances under her fingers. I cannot think about what the mistress of her keep will do if Wunmi does not return the day after her child is born. Or of how the baby will squall, mouth like a tornado, shrieking and crying and shaking the earth to find what has been denied it, seeking shelter in an uncaring world. Instead, I think of the old stories, the tales I know like the folds in my skin. The beginning of everything.

I tell him.

“We all used to have it. Magic, I mean. Olorun blessed all of mankind with it, different kinds that were meant for us to use to help each other.”

I spread my fingers, and the wind spirits return, weaving into shapes like threads building a tapestry. Soon there are fourteen people sitting shoulder to shoulder in a circle, arms raised to the fire in their midst—tiny ghostly figures.

“Our magic began as that. Gifts to each of the seven tribes, men and women. Some received the power to heal, others to call truth up to another’s lips and so much more. Some could even change shape and form. Our ancestors called themselves the first Oluso. Spirit-born. They created the land of Ifé and spread out into various regions. Oyo to the west, Eingard to the north, Berréa to the south, and Goma to the east. There was peace for a time . . . and then things changed.”

The ghostly figures morph into mist, and in their place are lumpy, misshapen heaps, with arms and legs sticking out like spines on a rose, and red—darker than any rose—streaming onto the cloth covering the cot. Jonas edges back a little.

“Some of the Oluso began to fight, to wage war on one another in a quest for power. But doing this broke the sacred covenant, and because of that they paid a price. After that, all the children born to them were hollow. Aje.”

Jonas nods slowly. “Someone called me that last year. But I didn’t know what it meant.”

I look away from the piercing blue of his eyes, training my gaze instead on the image on the bed. It morphs again, forming small figures running about in a field. Children. They

are laughing and singing, calling to one another, dancing. But one is hanging off to the side, away from the others, alone. It reminds me of the monthly village meetings on market day, and the way some of the adults stare at my mother when she speaks during them. Of those evenings when I come back after spending the day with the village children with bits of pawpaw stuck to my skin and purpling bruises the size of tomatoes. On those evenings, Mummy tells me of our history, of what it is to be Oluso, while scrubbing the sticky resin away, but my head is filled with images of the other children, their mouths wide like the mami wata that hides in rivers, their grasping hands dragging me into the sea of their hate.

“It means you are normal. Free to live your life without fear of being trapped and killed,” I say through gritted teeth. “For breaking their vows, Oluso who killed or used their powers to harm the innocent paid a grievous price. They lost their powers very slowly, and with it, their minds. And the children born to them were born without magic. Once people saw what was happening, they changed their ways, for fear of becoming Aje too. That is what it is. To Oluso, Aje are broken people. People with no link to the Spirit Realm. You’re born to wander the earth until your spirits return without tasting the joys of your natural powers. But to the rest of the kingdom, you are normal, human. There are more people like you, and less like me, so those of us with powers must be hunted down.”

“Isn’t it more than that?” Jonas asks, an edge in his voice. “Aren’t there magic users who still use their powers against the weak? There was the attack on the regional governor last year, and the massacre ten years ago that started the war—”

“No!”

I shout the word before I can stop myself. My hands are shaking, and I quiver as though a cold draft has entered the room, but he does not notice. His face is a thunderous mask, his eyes hard and mouth set in a grim line. I clutch at the necklace around my neck, feeling the burn of cold iron until I brush against the ring hanging from it. All at once, the tension leaves me, like steam escaping a kettle. I savor the silky feeling of the ring and chant words in my head over and over again like a curse: I am not my father. I was not born evil.

Finally calm, I meet Jonas’s gaze, holding my head high.

“Oluso cannot kill. Not without a price,” I say again, speaking softly now. “Ten years ago . . . I don’t know. I wasn’t born yet. But I’m telling the truth. Losing the powers you have is like dying. I’ve heard stories—tales of Oluso who broke the sacred vow. There is a man in our village, Baba Seyi. He is

the local madman. He can’t even eat without help. Fifteen years ago, he started a fire in a rival merchant’s house that killed a child. He’s suffered for it ever since.”

Jonas sighs, his expression softening. “I . . . I didn’t mean to get so angry. It’s just”—he pauses, dragging a hand through his wavy, golden hair—“my mother. She got hurt ten years ago. I was one. A magic attack.”

I fold, suddenly ashamed. “I didn’t know. I’m sorry.”

There is raw pain in his eyes, and I have the sudden urge to hug him, to press him into my side and pour warmth into his slumped frame, the way Mummy does with me after every market day. Instead, I drop my hands from my necklace and curl them into fists at my side.

He shakes his head. “Don’t worry about it. It was a long time ago.”

I swallow, trying to hold in the sharp pain creeping up my throat, but soon hot tears blur my vision. It is in moments like this that I wonder whether the townspeople are right, whether I deserve every blow their children give me. Oluso are meant to use their powers for good, to help all of humanity. This is the great responsibility we must bear, the very reason we are born the way we are. When I hear stories like these, or see Baba Seyi in the streets, I find it hard to lift my head. Mummy always reminds me that we are people, too, and no single Oluso is responsible for the choices of another. But right now, before this boy, I feel so small. His words are a knife flaying me open.

Suddenly, I feel a burst of warmth as Jonas’s arms encircle me. The smell of earth and lavender tickles my nose as he presses his neck against mine. “It’s okay,” he says, “I don’t think it’s your fault. Like I said, it was a long time ago.”

My heart is thundering wildly in my chest, threatening to burst, and all I want to do is tear myself away and hide. Then he pats my back, stroking softly, and I go limp, leaning against him like a child clinging to its mother. My throat is tight, but when I finally catch my breath again, I whisper, “I’m sorry.”

“For what? Being born?”

I pull away, swiping my sleeve across my nose. “I’ll help, I promise. I’ll ask my mother to heal yours.”

His eyes widen. “Would you?” He furrows his brow and starts again, “No. You don’t have to do that. It wouldn’t work anyway. I wouldn’t have any money to pay you. And my father . . . my father would never agree to it.”

“Why not? It’s for your mother.”

“He doesn’t trust magic users.” He stops, choosing his next words carefully,

“As in, one of . . . one of your kind hurt my mother, so he wouldn’t believe that someone else would try to help her.”

I nod. “That’s exactly why we have to do this. We can change his mind. Don’t worry about the money, I’m sure my mother will be okay with it. Let me ask her. Please.”

He stares, his expression unreadable. When he speaks, his voice trembles. “You would do this? For me? Show me kindness even though we’ve just met . . ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...