- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

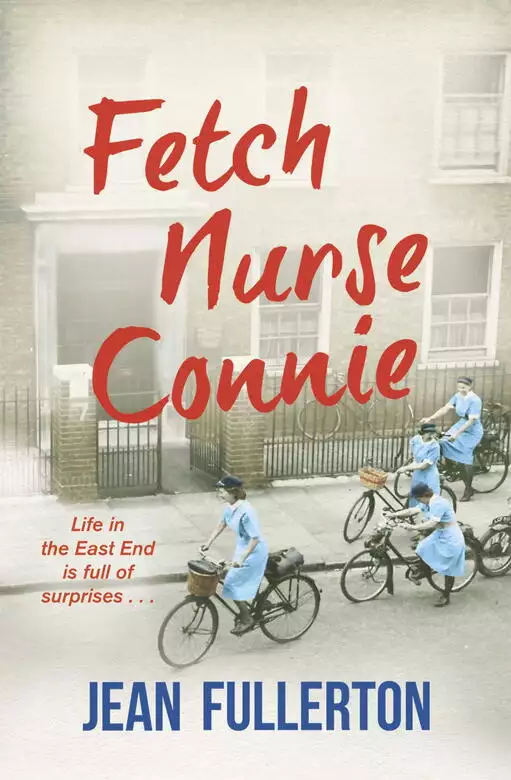

Synopsis

Connie Byrne, a nurse in London's East End working alongside Millie Sullivan from Call Nurse Millie, is planning her wedding to Charlie Ross, set to take place as soon as he returns from the war. But when she meets him off the train at London Bridge, she finds that his homecoming isn't going to go according to plan.

Connie's busy professional life, and the larger-than-life patients in the district, offer a welcome distraction, but for how long?

Read by Julie Maisey

Release date: June 4, 2015

Publisher: Orion Publishing Group

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Fetch Nurse Connie

Jean Fullerton

Chapter Seven

Connie lifted the set of forceps out of the disinfecting fluid, shook off the excess and then set them alongside the rest of her instruments on the sterile paper. Folding the paper into a neat package around her equipment, she carefully stowed it in the pocket of her case ready for her first visit. Just as she put the lid back on the metal tray, the street light outside went off.

She glanced up at the clock above the door. Five to seven. Just enough time for a leisurely breakfast before morning report.

She suppressed a yawn and opened the half-glazed door of the dressing cupboard. Inside, like a wall of battered metal bricks, were neatly stacked tins of gauze for new patients. Each evening the nurses rotated the duty of preparing the next day’s dressings by cutting gauze into squares and packing it into unpainted tins ready to be baked in Munroe House’s old-fashioned black-leaded range until the edges were brown. The on-call evening nurse would remove them from the oven when they’d cooled and replenish the stores each morning before she went off duty.

Selecting three tins for her morning calls, Connie packed them alongside the cleaned instruments. She closed the cupboard and was just about to fasten her bag when she heard a car door slam in the street outside. An engine revved and there was a screech of wheels as the vehicle sped away. The gate into the back yard creaked open. As she peered through the sheen of early-morning ice covering the rear window, Connie’s mouth pulled into a firm line. Snapping her case shut, she slipped it under the chair at the top of the table and marched out into the hall. The faint sound of singing through the half-open kitchen door indicated that Mrs Pierce, the new cook, was already at her post.

Clasping her hands in front of her, Connie stood in the middle of the carpet runner with her eyes fixed on the back door. After a couple of seconds the brass handle turned slowly. The door edged open and Gladys slipped through the gap. She was dressed in a royal blue satin evening dress with open-toed court shoes, and had a short fox fur shrug around her shoulders. Her russet hair was gathered into an untidy bird’s nest on top of her head, with only a feather grip holding it in place, and her mascara and lipstick were smudged.

‘Good morning, Sister Potter,’ Connie said pleasantly. ‘Or should that be good night, since you look ready for bed rather than a full day on the district.’

Gladys blinked and screwed up her eyes. ‘You what?’

‘Where have you been?’ Connie asked.

‘Out.’ A scornful expression spread across Gladys’s heavily made-up face. ‘Not that it’s any of your business, but my fella took me to the Sunset Club in Carnaby Street, and a right posh place it was too, though I don’t expect you’ve ever been there or even heard of it.’

‘I have, actually,’ Connie replied. ‘But you wouldn’t find me in such a sleazy dive.’

Gladys’s assurance wavered. ‘Yeah, well, my Raymond’s friendly with the owner. In fact, everyone knows him up West.’

‘That doesn’t surprise me,’ Connie replied, regarding her coolly.

Gladys gave her a belligerent look and headed for the stairs.

Connie stepped into her path. ‘You do know you’re supposed to be on call from eight, don’t you?’

‘And I’ll be ready as soon as I’ve got my uniform on,’ Gladys replied, breathing liquor fumes in Connie’s face.

Connie moved her head away. ‘You can’t visit patients like that.’

‘Like what?’

‘Drunk.’

‘I ain’t drunk,’ Gladys replied, wobbling on her shoes.

Connie raised an eyebrow. ‘Well you’re certainly not sober. And look at the state of you.’ Her eyes ran over the laddered stockings and creased dress, then rested on a love bite just peeking out from Gladys’s collar. ‘You’re a disgrace to your vocation.’

An angry flush reddened Gladys’s face. ‘Who the bloody hell—’ One of her clip-on earrings slipped off and bounced on the floorboards. She scrabbled after it.

Connie gave her a contemptuous look. ‘Why don’t you just go upstairs before the others see what a sorry excuse for a nurse you really are? Go on. I’ll tell Miss Dutton you’re sick.’

For one moment she thought Gladys was going to argue further, but then the other girl staggered backwards, catching the banister to steady herself. ‘As it happens, I don’t feel all the ticket.’ She swung around on the bottom post before tottering precariously up the stairs to her room.

Connie watched her until she disappeared, and then walked back into the treatment room. She went over to the duty blackboard and, picking up the rag, wiped Gladys’s name off the on-call rota and wrote her own instead.

Connie perched unsteadily on the edge of the chair. She had to, because most of the seat was taken up with back issues of the Lancet. On the floor to her left and almost at the same height as her knees was another pile of dog-eared periodicals, but this time it was the British Medical Journal.

The Redmans Road surgery was just a stone’s throw from Charrington’s brewery on the Mile End Road and occupied the downstairs rooms of an old printworks, upstairs being a secretarial employment agency. Dr Carter had moved into the present site only a few weeks ago, after an unexploded bomb left by the Luftwaffe decided to get on with the job and blew the best part of Redmans Road to kingdom come. The old surgery that the Carters, father and son, had occupied for almost half a century was among the casualties. What surrounded Connie now was what the locals had salvaged from the rubble.

‘Would you oblige me by running through the list thus far, Sister?’ asked Dr Carter the younger, who had taken over from his father before the war.

Weaving his fingers together across his fob chain, leaning back in his old leather chair he contemplated the far wall where his medical certificates were displayed.

William Rutherford Carter must have been nearer fifty than forty, but with a surprisingly full head of golden-brown hair, he looked younger than his years. As ever, he was wearing his tweed jacket with the leather-patched elbows, and worn corduroy trousers, as if he were taking a prize pig to the country fair rather than inspecting boils and haemorrhoids.

Connie glanced down at her notebook. ‘I have Mrs Smith, Ogleby, Shaw and Hollis for maternity; Mrs Cornell, 48 Sydney Street, for a soap and water enema until we get a result; Mr Emery, 12 Cressey Place, for a morning wash and weekly bath, and Mrs Aster for a right leg ulcer.’ She turned the page. ‘And six-year-old Clifford Grant to teach his mother how to set up a vapour tent for his asthma.’

Dr Carter pulled his pipe from his top pocket and tapped it out on the ashtray at his elbow. ‘Young Master Grant is turning into a delicate child; a referral to the Invalid Children’s Aid Association might be in order.’

‘Yes, Doctor.’

‘And perhaps you could let the do-nothings at the council know he’ll need a bit of supplementary teaching at home because of his wheezy lungs.’

Connie bit her lip. ‘I thought they needed a letter from you?’

A lordly smile lifted the corner of Dr Carter’s lips. ‘I’m sure they’ll waive the formalities for a pretty little thing like you.’

Feeling her cheeks start to colour, Connie looked down at her notebook. ‘Is there anyone else you’d like me to visit?’

‘Oh yes, I almost forgot. Mrs Cottrell’s being sent home from Guinness Ward tomorrow.’

Connie looked astounded. ‘Nelly’s still alive?’

‘Apparently so.’ Dr Carter shrugged. ‘It seems to fly in the face of all reason, not to mention Darwin’s theory of the survival of the fittest, but it seems that double pneumonia and septicaemia still aren’t enough to shuffle Nelly Cottrell off this mortal coil.’ His gaze ran over her face. ‘Do you know, Sister Byrne, you have very pretty eyes.’

‘Thank you, Doctor,’ Connie replied, somewhat taken aback. ‘Er . . . what would you like us to do for Mrs Cottrell?’

Dr Carter brushed a speck of dust from his sleeve. ‘Whatever you like, Sister. At eighty-nine, there’s not much more modern medicine can do for her, so I’ll leave it in your very capable hands.’ He tossed curled-up notebooks, prescription pads and leaflets aside until he found a sheet of flimsy pink paper on his roll-top desk. ‘You’d better have a copy of her hospital letter.’

He held out the carbon copy to Connie. As she took it, his fingers brushed over hers, and a lazy smile spread across his face.

Connie looked down at her notes. ‘Is that all?’

‘For now, although no doubt I’ll have another dozen pregnant women asking for maternity services when I next see you.’

Connie closed her notebook and slipped it into her pocket.

‘I don’t usually listen to patient gossip, but I couldn’t help but overhear recently that you’ve been disappointed,’ said Dr Carter, his chair creaking as he shifted towards her.

‘Disappointed?’

‘In love?’

‘Oh!’

His gaze searched her face. ‘Well all I can say, Connie – you don’t mind if I call you Connie, do you?’

‘I suppose not . . .’

‘All I can say is this fiancé of yours must be a very foolish young man.’ He shifted forward again. ‘Very foolish indeed.’

‘He’s not my fiancé,’ Connie replied, a lump of desolation in her throat. ‘Not any more.’

Her eyes felt tight so she looked away.

‘I’m sorry to cause you pain, and I wouldn’t have spoken except, you see, I know what it feels like to be rejected,’ he said, his face the epitome of misery. ‘My wife . . .’

‘I didn’t know.’

‘Yes. Two years ago.’ Dr Carter’s wretched expression lifted a little. ‘Of course, we hadn’t really been a couple for years, but . . .’ He rested his hand on Connie’s knee. ‘You know, if you ever need a shoulder to cry on . . .’

‘You’re very kind.’

‘Perhaps we could go for a drink. I know this little place in Cheapside.’

Mercifully, the black telephone on his desk sprang into life.

‘Thank you, Doctor.’ Connie jumped to her feet. ‘I’m sure you have at least a dozen important things to do, so I won’t take up any more of your time.’

Before he could reply, she had picked up her case and dashed out of the room.

‘Hold still,’ laughed Connie, as she wiped the gauze laden with benzyl benzoate over the sole of Grace’s right foot.

‘I can’t,’ giggled Grace. ‘You’re tickling me.’

She was back in the Tatums’ front lounge, helping Grace and her mother to apply the second scabies treatment. The first, a week ago, had probably done the trick, but the second treatment was standard practice. It was the end of a very long day. The afternoon clinic had been worse than usual, with the arrival of two emergency cases – a woman from a nearby sweatshop who had been scalded by steam, and a man who’d somehow managed to get his hand caught in some machinery. Thankfully, Beattie and her student were back early so they’d helped out, but Connie still hadn’t managed to send the last patient on their way until gone 5.40.

The door opened and Mrs Tatum strolled in wearing her silky dressing gown, her blonde hair whirled up into a topknot.

‘All done?’ she asked

‘Yes, we are,’ said Connie, dropping the used gauze on the newspaper by her side. ‘But it wouldn’t have taken so long if someone wasn’t so ticklish.’ She gave Grace her severe matron look and the young girl giggled again.

Mrs Tatum smiled fondly at her daughter, who was also in her nightdress and dressing gown. ‘What do you say to Sister Byrne?’

‘Thank you, Sister Byrne.’

‘My pleasure,’ said Connie, popping the cork back in the brown bottle containing the lotion and stowing it in her bag. ‘It’s all in a day’s work.’

‘No, really,’ said Mrs Tatum. ‘You’ve put yourself out and saved us an awkward journey. I am very grateful.’

Pushing her feet into her slippers, Grace rose and went over to the fireside chair. She picked up the copy of Black Beauty lying on the seat, then snuggled back against the cushions and opened the book.

Connie stood up and arched her back to ease the tightness in her spine.

‘Are you rushing off, Sister?’ Mrs Tatum asked as she tidied away her last few bits.

‘Not really,’ Connie replied.

‘Well then, why don’t I make us both a nice cup of coffee?’ asked Mrs Tatum.

Why not? Connie thought. She had her instruments to sterilise and restock for tomorrow, but as she had managed to get out of the evening’s trip to the Regency, she had plenty of time to do that.

‘That sounds perfect,’ she said.

Mrs Tatum smiled approvingly. ‘Good. You put your feet up and I’ll be back in a jiffy.’ She stoked up the smouldering coals in the grate, then left the room.

The fire crackled, and from the back of the house ‘Begin the Beguine’ drifted out. Taking her bag with her, Connie walked over to the sofa and sat down to write up her notes. Having completed the entry, she slipped the notes into the side pocket and leant back. Her eyes drifted up to the large portrait of Mrs Tatum and the older man on the mantelshelf.

‘That’s my dad,’ said Grace.

‘I guessed as much,’ Connie replied.

‘He died when I was a baby.’

‘Oh dear.’

‘Yes,’ continued Grace in a matter-of-fact tone. ‘He was knocked over by a bus in Aldgate on his way to work.’

‘I’m sorry.’

‘It’s all right,’ said Grace with a little shrug. ‘That picture was taken before I was born. I don’t remember him but Mummy’s told me all about him.’

Connie smiled. ‘I’m sure she has.’

‘He worked in a bank in the City and . . .’ a frown wrinkled Grace’s brow, ‘I think he worked with people in other countries or something. I’m not too sure but he was very high up.’

Given the comfortable house Grace and her mother lived in, Connie wasn’t surprised to hear this. Whereas most families made do with a couple of rooms, Mrs Tatum had the entire house to herself, not to mention the small bedroom on the half-landing that had been turned into a bathroom. No zinc bath in front of the fire for Grace and her mother, and each room had a fire in the grate, which must have cost a pretty penny in coal each week.

‘Do you think I look like him?’ asked Grace.

‘Maybe a little bit,’ said Connie tactfully. ‘But perhaps you take after your mother more.’

The door opened and Mrs Tatum walked in carrying a tray with their coffee, a glass of milk and a plate of something Connie hadn’t tasted for five years: chocolate digestives.

‘There we go,’ she said as she put the tray on the low table in front of the sofa. ‘Sugar, Sister?’

‘One, please,’ Connie replied.

Mrs Tatum handed her a cup, then offered her a biscuit. Connie took one and tucked it on the side of her saucer. Mrs Tatum put a gentle arm around her daughter’s shoulders.

‘Perhaps you’d like to take your milk and biscuit into the dining room and get on with your homework while Sister Byrne and I have our coffee.’

‘Yes, Mummy,’ said Grace, putting the book aside. She slid off the chair, collected her drink and snack and walked towards the door.

‘And don’t forget it’s not long until the entrance test, so make sure you learn the extra spellings I gave you,’ Mrs Tatum called after her.

‘Yes, Mummy,’ Grace called behind her as she closed the lounge door.

Connie took a bite of biscuit. ‘Goodness, that’s delicious.’

Mrs Tatum smiled and sipped her coffee.

‘Which school are you trying to get Grace into?’ Connie asked when the chocolate in her mouth had finally dissolved.

‘Coborn School for Girls, in Bow,’ Mrs Tatum replied.

‘My friend Millie went there,’ said Connie. ‘It’s a good school, but I’ve heard it’s even more difficult to get into now, as there are only a few scholarship places each year and there’ve been double the applicants since the return of the evacuees. Although, from what I’ve seen of Grace, I’d think she’d sail through the entrance test.’

A worried look clouded Mrs Tatum’s face. ‘I do hope so. I want her to join a profession, like teaching or nursing. Since she met you, she’s set up a hospital ward with her dolls.’

Connie smiled. ‘I’m sure she’d be an excellent nurse, but nursing is a vocation, not a profession. I went to Raine’s, and lots of my class became personal secretaries and teachers, but I’ve felt called to be a nurse since I was Grace’s age and never considered doing anything else.’

‘Well at least with a good education she will be able to stand on her own feet financially,’ said Mrs Tatum.

Connie smiled. ‘Perhaps she’ll go into banking like your husband.’

Mrs Tatum looked blank for a moment, then a dazzling smile spread across her well-favoured face.

‘Ah yes, dear Gerald.’ She stood up and walked over to the mantelshelf. ‘Such a wonderful man,’ she said, picking up the portrait.

‘You both look very happy,’ said Connie.

‘We were,’ she said, gazing adoringly down at the photo. ‘This was taken at the Café Royal just after Grace’s first birthday and only a week before he stepped out in front of a bus in Piccadilly.’

‘Piccadilly?’ said Connie. ‘Grace told me her father was killed at Aldgate.’

Mrs Tatum’s cheeks flushed. ‘Aldgate! Oh . . . yes . . . yes.’ Her assured smile returned. ‘Aldgate. Of course it was. Silly me. How could I have forgotten?’

Leaving mother and daughter to their quiet evening in, Connie cycled the half a mile back to Munroe House. She was more than ready to tuck into her supper, but as she turned the corner of Roland Street, her heart leapt into her throat.

Leaning casually against the wall was Charlie, dressed as if he was going out for the night, with a cigarette dangling from his right hand. When he spotted her, he took a last drag on his cigarette and stood away from the brickwork.

With the blood pounding through her ears almost deafening her, Connie rolled to a stop and stepped off her bike.

‘Hello, Connie,’ he said, in that warm, honey tone guaranteed to melt her bones.

Although she shouldn’t have let them, her eyes roamed freely over his face, noting the contrast between his soft cheeks and harsh bristle, the golden flecks in the blue of his eyes and the bluntness of his chin.

‘What are you doing here?’

‘Waiting for you,’ he replied, flicking his spent cigarette into the gutter. ‘I just wanted to talk to you, Connie.’

‘What about?’

‘Well, seeing you the other day made me think that perhaps you and me could straighten things out.’

With something akin to a millstone pressing down on her chest, Connie tore her gaze from his face.

‘I’m late for supper.’

‘I just want to have a little chat with you, Connie, that’s all,’ he pleaded, raking his fingers through his hair in that oh-so-familiar way. ‘To say I’m sorry. Properly.’

Connie gave a harsh laugh. ‘Don’t you think it’s a bit late for that?’

‘Maybe, but . . . Look, I’ll be in the snug in the Rose and Punchbowl at eight on Friday—’

‘Goodbye, Charlie, and give my regards to Maria,’ said Connie. Concentrating on the spinning spokes of her front wheel, she rolled her bike past him and into the back yard of Munroe House.

‘I’ll be there until closing if you change your mind,’ he called after her.

Although the melodious strings of the BBC orchestra drifted out across the nurses’ lounge, Connie was no more listening to the music than she was reading the book propped open on her lap. How could she? The image of Charlie waiting for her outside the back gate materialised in her mind for the umpteenth time, but she cut it short and glanced at the clock. Almost nine, and with a bit of luck Millie would be back soon; in fact Connie was surprised she wasn’t home already.

‘Good book?’ called Beattie from the other side of the room, where she and Sally were playing draughts.

Dragging her mind away from her feckless ex-fiancé, Connie forced a smile. ‘Yes, very romantic.’ She looked down at the title printed across the top of the page, only to find she’d picked an Agatha Christie novel from the shelf. She turned a page and pretended to be engrossed.

The music recital came to a close, and just as the plummy tones of the presenter announced the following quiz programme, the door opened and Millie walked in. Her fatigued eyes searched the room until she spotted Connie, and then she made her way over.

Connie put the book aside. ‘How’s your mum?’

Millie flopped next to her on the sofa. ‘So-so.’

‘These things take time,’ said Connie.

‘I know,’ Millie replied. ‘And now that all the shops are getting decked out for Christmas, she’s thinking about what it will be like without Dad.’

The door opened and Mary, the evening maid, still in her pinafore and white cap, pushed in the trolley loaded with a dozen mugs of hot milk, Ovaltine and cocoa.

‘You stay put. I’ll get it,’ Connie said, standing up. ‘What do you want?’

Millie rallied a weary smile. ‘Ovaltine, thanks.’

Leaving Millie with her head resting back on the lacy sofa cover and her eyes closed, Connie went to fetch their bedtime drinks.

‘There you go,’ she said when she returned clutching two mugs in one hand and a plate in the other. ‘And I’ve got us a couple of digestives to soak it up.’

‘So what have you been up to today?’ asked Millie.

‘Oh, this and that.’ Connie took a sip of her drink. ‘Charlie was waiting for me at the gate when I got back.’

Millie’s mouth dropped open. ‘He’s got a nerve!’

‘Said he wanted to have a little chat,’ explained Connie.

‘About what?’

‘Getting things straight between us.’

‘It’s too late for that, isn’t it?’

‘It was too late the moment he stepped off that train,’ agreed Connie. ‘He even had the cheek to ask me to meet him in the Rose and Punchbowl on Friday. I told him to give my regards to his wife.’

‘Good for you,’ said Millie. She reached down and retrieved a copy of Woman’s Weekly from the magazine rack beside the chair.

Cradling her cocoa, Connie raised it to her lips. ‘He said he’d wait until last orders in case I changed my mind.’

Millie’s head snapped up. ‘You’re not thinking of going?’ she asked, scrutinising Connie’s face.

‘Really, Millie!’ Connie laughed, not quite able to look her friend in the eye. ‘What sort of idiot do you take me for?’

Chapter Eight

Staring at the faded candy-striped fabric of the portable screen, Connie worked her way down the six-month bulge of Freda Johnson’s stomach as she tried to visualise what was beneath her fingertips.

It was the third Thursday in November, and as usual the antenatal clinic was packed with pregnant women and fractious toddlers. Connie, Hannah and Pat, the new student Queenie who was assisting them, had all bolted down their lunch so they could get the treatment room in order before the first expectant mothers arrived. The three antiquated fabric screens had been wheeled out and lined up either side of the two examination couches in readiness. They were supposed to provide privacy, but as they were almost transparent with age and washing, they were of little effect. Added to which, the two rows of chairs were set out so close to the screens that those waiting could pass the time by listening in on the consultation only a few feet from them.

The rain had been lashing against the windows since dawn, so not only was there the usual odour of cigarettes and full nappies in the cramped clinic but also the smell of damp wool. If that wasn’t enough to give you a headache, then the screams of babies wanting to be fed and the shouts of protesting toddlers were guaranteed to.

Stretching her hand wide, Connie grasped just above Freda’s pubic bone and found the baby’s head immediately.

‘He’s head down,’ she said, smiling at the round-faced brunette with her petticoat pulled up under her chin and her well-washed knickers tucked beneath her bump.

Connie had delivered Freda’s first baby – a bouncing ten-pound boy – in an Anderson shelter during a night raid in June 1940. Young William had been an easy delivery, as had John, Ruth and Marge who’d followed, so Connie was confident that number five would be much the same.

‘That’s all fine, Mrs Johnson,’ she said, reaching for the Bakelite instrument on the stainless-steel trolley beside her. ‘But if I could just listen to baby’s heart.’

‘Course you can, luv,’ said Freda.

Pressing her ear to the narrow end of her foetal stethoscope, Connie watched the second hand on her watch turn for half a minute while counting the heartbeats. She doubled the number in her head before straightening up with a smile.

‘Spot on. You can get up now.’

As Freda adjusted her clothing and got off the couch, Connie wrote up her observations.

‘I’d like to see you on the third of January, and then every two weeks.’

‘Right you are, Sister,’ said Freda, winding a long knitted scarf around her neck and taking a pack of ten Woodbines from her pocket.

Connie smiled and handed Freda her notes. ‘Could you give these to the nurse at the desk?’

Once Freda had gone, Connie poured some surgical spirit on to a gauze square and wiped her stethoscope and tape measure, then replaced the antiseptic paper on the couch. Satisfied that everything was in order, she stepped through the gap between the screens.

‘Next,’ she called above the hubbub of voices.

A young woman with blonde hair cropped becomingly around her ears, wearing a fitted brown coat and a bright red felt hat with matching handbag, stood up.

‘That’s me, I think,’ she laughed, beaming around at the women surrounding her. Sensing a first baby in the offing, they smiled indulgently as she picked her way between the children and pushchairs towards Connie.

‘This is all new to me,’ she giggled, handing Connie her notes. ‘It’s my first.’

Connie smiled and glanced at the name on the top. ‘Mrs Valerie Webb?’

The young woman nodded. ‘That’s me, and call me Val.’

‘I’m Sister Byrne,’ said Connie, closing the curtain behind her. ‘And you’ve come to book in with us today?’

‘I have,’ said Mrs Webb. ‘I might be a bit too soon, but my Ron said I ought to come to make sure everything’s all right.’

‘That’s very sensible of him,’ said Connie.

A fond look stole over Mrs Webb’s pretty face. ‘He’s like that. Ever since he got back, he can’t do enough for me. He even hung out the washing yesterday before he went on shift so I didn’t have to stretch up.’

Connie smiled politely. ‘Please take a seat.’

Mrs Webb tucked her skirt under her and settled in the straight-backed chair beside the couch, putting her handbag on the floor beside her.

Connie reviewed her medical history, noting that her blood pressure was normal, that nothing untoward had shown up in her urine and that her last period had been approximately nine weeks before, making her due date the end of May.

‘I see you’ve been married for four years and your husband works at Crane Wharf,’ said Connie.

‘That’s right,’ said Mrs Webb. ‘The manager gave him his old job back without a quibble. Well, they had to or he’d have had them all down tools. He’s a shop steward, you see.’

Connie nodded. ‘And you live in Smithy Street.’

‘Only until we can get a place on the new estate in Dagenham.’ She put her hands on her stomach and glanced down. ‘Ron and me want our baby to be brought up in the country.’

Connie perused the notes again. ‘I can see we’ve got a full history of your family’s health but not very much about your husband’s.’

‘His mother’s as fit as a fiddle, more’s the pity.’ Mrs Webb looked apologetically at Connie. ‘I know I shouldn’t say it, but we live with her and it’s not easy. She has family in Hackney, I think, but they could be dead for all I know. There was an almighty bust-up years ago, before I met Ron, and his mother has had nothing to do with them since. Sorry.’

Connie put Mrs Webb’s notes on the trolley next to her equipment. ‘Oh well, never mind. If you just take off your coat and hop up on to the couch. I probably won’t be able to feel anything much until at least three and a half months, but I like to do a quick examination, if you don’t mind.’

‘All right. That’s fine with me,’ said Mrs Webb.

She stood up and slipped off her coat to reveal a stylish burnt-orange button-through dress with padded shoulders and a pencil skirt. Connie’s eyes flickered over the seams pulled tight across her stomach. Draping the coat over the back of the chair, Mrs Webb stepped out of her shoes and, placing them beside her handbag, climbed on to the couch.

‘If you could just wriggle your skirt up to your waist and your knickers down to your hips, I think that will be fine,’ said Connie.

Mrs Webb eased her slimline skirt up to reveal a pair of very lacy French knickers and a suspender belt holding up her nylons.

‘My Ron brought them back from France,’ she explained.

Connie smiled. ‘I’m just going to run my hands over your tummy, so I want you to relax.’

Mrs Webb nodded and lay back.

Like t

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...