- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

The 21st century.

Europe is divided between the First World bourgeoisie, made rich by nanotechnology and the cheap versatile slave labour of genetically engineered Dolls and the Fourth World of refugees and homeless displaced by war and economic upheaval. In London, Alex Sharkey is trying to make his mark as a designer of psychoactive viruses, whilst staying one step ahead of the police and the Triad gangs. At the cost of three hours of his life, he finds an unlikely ally in a scary, super-smart little girl called Milena, but his troubles really start when he helps Milena quicken intelligence in a Doll, turning it into the first of the fairies.

Milena isn't sure if she's mad or if she's the only sane person left in the world; she only knows that she wants to escape to her own private Fairyland and live forever. Although Milena has created the fairies for her own ends, some of the Folk, as fey and dangerous as any in legend, have other ideas about her destiny ...

Read by Max Dowler

Release date: December 30, 2010

Publisher: Orion Publishing Group

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

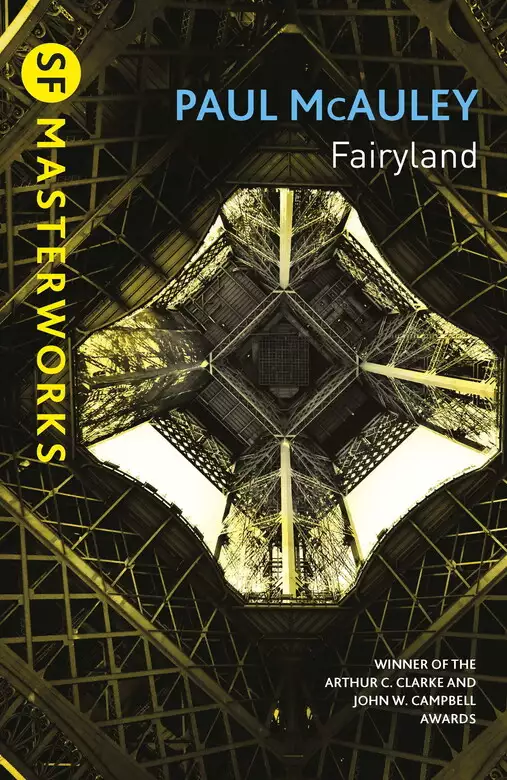

Fairyland

Paul McAuley

Perhaps McAuley has become best known for expansive, if often dark, visions, from the galactic Eternal Light (1991) to the inter-planetary Quiet War sequence (2008-13). But much of his most memorable work has been set in locations much closer in space and time, such as the near-future England of the recent Something Coming Through (2015) – and the remarkable and award-garlanded Fairyland (1995), set mainly in early-twenty-first-century London (McAuley’s home), Paris and eastern Europe.

The book opens, in fact, in the very recognisable environs of Kings Cross, where gene hacker Alex Sharkey is pursuing dubious business deals. This is a future awash with strange and harmful technologies – such as the ‘psychoactive viruses’ Sharkey himself manufactures – but it is founded on the relics of the past. McAuley likes to build elaborate futures and then make them lived-in, weathered, overwhelmed by change and obsolescence and cluttered with rubbish – his futures are ‘rendered down’, they are ‘distressed’, as the special effects artists might say, and all the more believable for it. But there is spot-on prophecy here too; London is being transformed by the ‘Great Climatic Overturn’, and while an elderly privileged elite live in ‘ribbon arcologies’ on the perimeters of the cities, ‘migrants . . . flock . . . into the heart of Europe like swallows’.

The storyline is driven by the slow revelation of a still stranger phenomenon. Sharkey encounters ‘dolls’, strange subhuman creatures, genetically engineered but simple-minded, who are used for labour, as sex toys, as snuff fighters – in one example of the satirical black comedy that runs through this book, they are put to work in burger bars. But an enigmatic young woman called Milena, herself the product of programmed genetics, is experimenting with the dolls, trying to uplift them to high intelligence. McAuley’s work could not have been more up to date, but it is also knowing of its genre background; Milena, from her point of view like a human raised by apes, makes Tarzan jokes.

And, delving into deeper myth, the uplifted dolls become called fairies, or the Folk, and – especially in the book’s last section, set in myth-soaked eastern Europe – they begin to play a role in our lives associated with the darker version of that strand of folklore; they can dazzle humans with their technologically based glamour, and they steal human children, meaning to transform them into ‘changelings’. Milena herself becomes identified with intervening goddesses, with Mab and Mary. As if old nightmares are released by the newest technologies.

If all this sounds a little dry, note that much of the plot in the central section of the book is driven by the very human story of a paramedic searching for a refugee child taken by the Folk, a selfless hero trying to save a child the rest of her society regards as worthless. Indeed the wider frame is a hopeless love story, of Sharkey and his impossible girl Milena. McAuley has always had an instinct for a good story. And while he sometimes seems to despair of humanity, he is always humane.

There is undoubtedly a moral force to the book, a sense that we are reading an if-this-goes-on warning of a dire future. In another in-joke McAuley has the first mission to Mars, a staple of traditional ‘hard SF’ (indeed McAuley himself had gone to Mars only a couple of years earlier, with Red Dust), play out almost unregarded on the TV screens in the background of his troubled world. ‘I see this Mars landing as the forward point of progress,’ says one character, ‘pulling the rest of humanity behind it.’ ‘Yes,’ replies the paramedic, ‘and I remember the right wing economic theories of the last century, all that rubbish about creating a wealthy elite that would enrich the whole community. We’re still living with the problems that caused.’

The book’s most striking set-piece is perhaps a metaphor for this thesis. One reading of the title ‘Fairyland’ is that it refers to an abandoned theme park outside Paris, called coyly here the ‘Magic Kingdom’, whose ruined attractions are inhabited by the Folk and those who serve them: a very black joke, a ghastly juxtaposition of over-commercialised dreams and out-of-control technology. The Folk, super-intelligent, endlessly experimenting, casually release viruses and nanotech into the very air, where it mutates in a Darwinian fashion. Some of the results are valuable, and the Magic Kingdom is surrounded by an ‘Interface’, a kind of gold-rush belt where corporations and private individuals sift the results for saleable tech. But, perhaps as an image of modern capitalism, there is no purpose save blind selection behind the endless churning of the technology, no motive in its harvesting save greed. In the end it’s hard to disagree with Leroy, protector of Sharkey’s mother, when he says: ‘Blow, now, it’s a natural high. It’s an ‘erb, something God Himself made for us to use. The stuff you make, Alex, it’s devil work. It’s the way the world got fucked up.’

But despite the darkness there is never less than a sense of wonder in McAuley’s imaginings: ‘Fairyland isn’t a place, it’s a hyperevolutionary potential. It is where we dream ourselves into being.’ Indeed.

Paul McAuley is a man of great personal and moral courage, and possessor of a fierce intelligence. It’s hard to believe Fairyland is twenty years old. But it is as relevant, and as vibrant, and as necessary today as when it was first published.

Stephen Baxter9 October 2015

The room is full of ghosts.

Transparent as jellyfish, dressed in full Edwardian rig, they drift singly or in pairs around and around the newly restored

Ladies’ Smoking Room of the Grand Midland Hotel at St Pancras, adroitly avoiding passengers waiting to board the 1600 hours

Trans-Europe Express. Alex Sharkey is the only person in the room who pays the ghosts any attention; to pass the time, he

has been trying to derive the algorithm which controls their seemingly random promenade. He arrived twenty minutes early,

and now, according to the watch he bought on his way here, it is twelve minutes past three, and his client is late.

Alex is edgy and uncomfortable, sweating into his brand-new drawstring shirt of unbleached Afghan cotton. The raw cotton is

flecked with nubbles of chaff that scratch his skin. The jacket of his suit is tight across his shoulders; although the salesman

assured him that its green tweed check complemented his red hair, Alex thinks it makes him look a little like Oscar Wilde,

who wouldn’t be out of place in the lovingly restored heritage décor of the Ladies’ Smoking Room, with its salmon pink and

cream walls, marble pillars and plush red upholstered easy chairs, its potted palms and flitting population of Edwardian ghosts.

Alex is wedged into a low, overstuffed armchair, chain-smoking and feeling the buzz from his second cup of espresso. One thing

he’s learned today is they make wonderful espresso here, oily and bitter and served scalding hot in decently thick thimble-sized

cups, with a twist of lemon in the bowl of the dainty silver spoon, and a bitter mint chocolate and a glass of flash-filtered

water served on the side.

Caffeine is such a simple, elegant, necessary drug – Alex remembers one of Gary Larson’s Far Side cartoons, goofy lions sprawled around a tree and off in the distance

a rhino pouring a cup of coffee for its mate, who’s saying, ‘Whoa, that’s plenty.’ The title was African Dawn, and Alex smiles now, remembering the way he laughed out loud the first time he saw it. Which was when? One Christmas back

before the end of the twentieth century, he must have been five or six. It would have been in the damp, ant-infested, twelfth

floor council flat on the Isle of Dogs, looking out over the Thames. Lexis always got him a book for Christmas, somehow or

other. To improve him.

And now here he is, surrounded by hologram ghosts and waiting for his man, trying to blend in with the suits and the rich

tourists waiting for the express train out of this shitty country. Most of them are chattering in French, the lingua franca of the élite of the increasingly isolationist European Union. The women are defiantly tanned, in flimsy blouses and very short

shorts, or miniskirts with artfully tattered hems. A few, this is the very latest in BodiCon fashion, are enveloped in chadors

made of layers of translucent chiffon woven with graphic film that flashes odd images and shifting patterns, revealing and

concealing breasts, the curve of a hip, smooth tanned skin hollowed over a collar bone. The men wear chunky suits in earth

colours, a lot of gold on their wrists, and discreet makeup. Earrings flash when they speak or glance at themselves in the

tall gilt mirrors behind the bar. Unnervingly, the mirrors do not reflect the ghosts. At the bar’s mahogany counter, half

a dozen Ukrainians in shiny black suits make a lot of noise, toasting each other with rounds of malt whisky.

One woman has a pet doll. It sits quietly beside its mistress, dressed in a pink and purple uniform edged with gold braid.

A chain leash is clipped to the studded dog collar around its neck. Its prognathous blue-skinned face is impassive. Only its

eyes move. Dark, liquid, sad-looking eyes, as if it knows that something’s wrong deep down in every cell of its body, knows

the burden of sin that’s been laid on it.

Alex feels sorry for it – it’s displaced from Nature, dazed by the violence done to its genome. It’s a crufty creature, he

thinks, the epitome of his belief that there’s no point gengineering anything more advanced than yeast: the more complex the

organism, the more unpredictable the side-effects.

Alex lights another cigarette and checks the time again. He has an edgy sliding feeling that things have gone wrong. He has

always hated waiting around, having to be on time. For this one occasion, when he had to be punctual, he bought a watch, and

all it does is make him more nervous. It is a piece of recyclable Polish street shit that cost less than a single espresso,

graphic film on a hexagon of varnished fibreboard, a bright orange cloth strap. It runs on the faint myoelectric field generated

by Alex’s wrist muscles – it’s a time-binding parasite. There’s a black eagle impressed on the watch-face, and the eagle raises

its wings and breathes fire when Alex tilts his wrist to look at it. The hands are black slivers generated by the same chip

that runs the eagle. The graphic film is already wrinkling: the eagle has a broken wing; the hour hand is kinked. It is eighteen

minutes past three.

Alex once had a genuine antique stainless steel oyster Rolex; it came with a certificate proving it was manufactured in Switzerland,

in 1967. It was given to him by the Wizard – the Wizard was always giving him stuff like that, in the days when Alex was the

brightest and best of the Wizard’s apprentices. But Alex lost the Rolex when he was banged up with the Wizard and the rest

of his crew. Either the cops or one of Lexis’s asshole toy boys swiped it. Alex lost a lot, then, which is one reason why

he’s in a hole with Billy Rock, and making risky, desperate deals with junior grade Indonesian diplomats.

Twenty-eight minutes past. Shit. Alex signals to the waiter and orders another espresso, speaking slowly and carefully because

the tall, silver-haired man is an Albanian refugee who has only a glancing relationship with the English language.

It’s twenty to four, and the boarding announcement for the Trans-Europe Express has been made, and the passengers are beginning

to leave, when the waiter brings Alex his espresso. Alex pays with a credit card which doesn’t have his name on it, knocks

back the coffee and walks over to the woman with the leashed doll. He stands there, looking at her. It’s silly and he knows

it won’t really make him feel better, but he has to do it.

When she finally looks up, a tanned woman of about forty with that tightness around her jaw that indicates a facelift, Alex

says, ‘I only just figured out that the animal at the end of the lead is the one getting smashed on Campari,’ and walks out of there, straight through two ghostly women in small-waisted day dresses

who break apart around him in spangles of diffracted laser light.

Gilbert Scott’s great curving stair takes Alex down to the busy lobby. He shakes out his black, wide-brimmed hat (yeah, Oscar

Wilde) and claps it on to his head, trying to look nonchalant despite the ball of acid cramping his stomach. A doorman in

plum uniform and top hat opens a polished plate glass door and Alex walks out into bronze sunlight and the roar of traffic

shuddering along Euston Road.

To the north, black rainclouds are boiling up, bunching and streaming as if on fast forward. There’s a charge in the air;

everyone is walking quickly, despite the heavy heat. Every other person carries an umbrella. It’s monsoon weather.

Alex takes the pedestrian underpass to King’s Cross Station. There’s a row of phone kiosks at the edge of the pavement, tended

by a crone in a kind of wraparound cape made of black plastic refuse bags. Alex tips her and, cramped in a booth that stinks

equally of piss and industrial deodorant, its walls scaled with the calling cards of the face workers of the sex industry,

dials his contact number. The Wizard taught him never to ring clients from a mobile phone – the locations of switched-on mobile

phones are constantly updated on lookup tables, microwave junctions are tapped, with AIs patiently listening in for keywords,

and anyone within fifteen kilometres can eavesdrop using an over-the-counter scanner.

The screen of the phone is cracked, and someone has spilled a bottle of black nail varnish over its lower quadrant. There’s

a blood-tinged hypo barrel on the floor. Alex kicks it around while the phone rings out, then leaves with a curious sense

of exhilaration, a floating rush like being in free fall. He is well and truly fucked. Sooner or later this will catch up

with him, but right now it’s as if he has escaped something.

Just as he starts towards the Underground, the rain comes down.

It comes down with a black fury, rebounding a metre in the air. Alex dodges into the station entrance, half-drenched. The

brim of his hat sheds water down his back. The rain is so intense you could drown in it. The temperature drops ten degrees in an instant.

The weather has been doing weird things lately. It’s in a hurry. It wants to get some deep change over with.

Black taxis suddenly all have orange occupied signs. Trucks plough up bow waves in the flooded road, swamping the pastel bubbles

of microcars. Alex sees blue flickers far up Pentonville Road, and tenses. No, it could be just an accident.

Wind gusts turn umbrellas and parasols inside out, snatch hats from heads. There is a refugee encampment on the traffic island

at the road junction of King’s Cross. Lashed by crisscrossing ropes to railings and the posts of traffic signs, the tarpaulin

and plastic sheeting of the benders and bivouacs belly and crack in the wind. A sheet of black plastic suddenly winnows out

in the pouring rain, goes sailing off above the traffic like a bat, then drops on to the windscreen of a truck. The truck

slews to a halt in the flooded road, belching vast clouds of black smoke that smells like boiling year-old cooking oil and

blocking both eastbound lanes. Horns, angry flickers of brake lights: red stabs in dark teeming air.

Distant blue lights revolve in the rain. Sirens start up, are cut short in frustration. Alex sees someone run into the stalled

traffic, a small guy pursued by two big beefy men in suits who grab his arms, pull him back. One of the men waves a bit of

laminated plastic at a taxi which blows its horn.

Oh Jesus, there goes his contact. Alex is suddenly certain that it’s Perse. Perse has found out and fucked him over.

Two police cruisers are caught in the jam of vehicles behind the jackknifed truck. The doors of one of the cruisers slam open

and policemen in yellow slickers scramble out.

Suddenly, Alex is intensely aware of the security cameras everywhere. He pulls his wet hat lower and walks into the crowded

station concourse. A vagrant in a filthy full-length overcoat belted with string grins at him. The vagrant’s forehead is cratered

with a purple and yellow crusted wound. He sees he’s got Alex’s attention and says, ‘This bloke gave me some bleach this morning

and I triaged myself. Poured it right on to my forehead and didn’t even get a drop in my eye. What do you think of that?’

Alex pulls the case from the inside pocket of his jacket – the striations of its black plastic cover seem to flex as it scans his prints – and thrusts it at the man. He says, ‘Fifteen minutes

ago I was going to be rich. Never trust a copper.’

The vagrant stares at what looks like a matt black CD jewel box and says, ‘Do you think I want to dance?’

But he takes it anyway, and that’s that. Contact with unrecognized fingerprints activates the suicide sequence, and in seconds

the case will cook its contents.

Alex is already hurrying away. The sound of rain on the high glass roof echoes above him like God’s impatient fingers, drumming,

drumming. He pushes through a line of passengers waiting to board one of the new radiation-proofed trains to Scotland, and

takes the stairs down to the Underground station. He doesn’t even bother to try and make a deal with one of the sellers of

secondhand travelcards, but feeds a machine with a five pound coin, grabs his ticket and runs down escalators and along tiled

corridors. Ozone-laden wind sandpapers his throat as he runs, a fat young man in a suit of vivid green check one size too

small for him, his face as pink as a skinned seal’s, clutching a broad black hat to his head, in a hurry to get somewhere

else.

Straphanging on the rattly old Metropolitan Line, Alex Sharkey just breathes for a while. Sweat soaks his shirt: he can feel

its nubbly material stick and unstick to his back as the train smashes through the dark. The carriage is crowded, and Alex

is squashed by one of the doors. A safety notice above his head has been detourned to read Obstruct the doors cause delay and be dangerous. Alex can almost believe it’s a message directed at him.

Alex changes on to the East London Line at Whitechapel for the short jog over to Shadwell, where he climbs the stairs and

waits a long while on the wet, windy platform for one of the little Docklands trains. After the Radical Monarchist League

blew up the Jubilee extension, travel between the centre of London and the East End has once again become terrifically inconvenient.

A middle-aged man in a suit, probably a journalist, hunches over a Bookman at the front of the carriage; weary East End women

sit with their shopping between their feet; a black kid, the hood of his poncho pulled up and the top half of his face masked

by an iridescent visor, talks into a mobile phone. Every now and then the kid leans his arm across the back of his seat and

turns towards Alex, who wonders if maybe the kid thinks he looks like a copper.

He starts to laugh, a little constricted giggle that makes him shake all over. Because, Jesus, he really is in deep shit now.

He doesn’t even know if it’s safe to go home, but where else can he go? Leroy won’t thank him if he drags his trouble into

the shebeen, and there’s no way he’s going to put his mother through it again. When the police moved against the Wizard, an

armed team punched out the door of Lexis’s flat with a pneumatic jackhammer.

Alex gets off at Westferry. It’s stopped raining. Raw sunlight heats the air. Steam boils up from the road. There’s a smell

like fresh baked bread. Everywhere, light is shattered by water films. Mosquitoes whine, and even though he’s had shots against

yellow fever and malaria and blackwater fever, Alex pulls down the veil of his big black hat.

He remembers the years just after the birds died, the plagues of grasshoppers, aphids, flying ants and flies, the food shortages

and the long lines outside supermarkets. The little world Lexis drew around them both, back then – he should go and see her,

once this is over, once it’s safe. She’s getting on, and her current boyfriend is younger than Alex, for Christ’s sake. If

he’s safe, he’ll go and see her. He offers this up like a prayer. Home, safe and free. Playing tag in the stairwells of the

tower blocks, Alex was always anxious about being left out, being left behind – he was overweight even then, although he could

run as fast as most of the other kids, could wrestle most of them into submission, too. His weight gave him a presence – he

still likes to think that. He remembers the one girl who could outrun everyone. Tall, knock-kneed Najma, her thick black braid

sticking out as she flew across the ground. Gone now, gone away. Her family caught in one of the repatriation sweeps and sent

to India although they’d all of them been born here. If she’s still alive, what must life be like for her now? Alex should count his blessings.

He thinks all this as he takes underpasses beneath busy roads and skirts a threadbare acre of grass between tattered deck

access housing projects where kids play football amongst burnt-out cars, so many cars abandoned here it looks like a parking

lot. The pyramid-capped monolith of Canary Wharf disappears and reappears behind the tower blocks. The sun beats down, baking

the crown of Alex’s skull inside his black hat.

He has a bad moment in the unmade alley that runs past a scrap yard under the cantilevered Docklands line, but the two figures

at the far end of the alley are just a crack dealer and one of his runners. Alex vaguely knows the dealer, a muscled Nigerian

who always wears wraparound shades. There’s a baseball bat tucked under his arm, for sorting out argumentative customers.

The dealer nods languidly and asks Alex how it’s going, is he still making that strange shit?

‘You want to sell some for me?’

‘Oh man, there’s no percentage in that stuff. My customers know exactly what they want. You should be getting into that, man.

You cook me some DOA, I can move it for you no problem. You worked for the Wizard, man. Any stuff you cook up will sell, I

guarantee it. The punters appreciate a good pedigree.’

They’ve had this conversation before, but Alex isn’t crazy or desperate enough for this sort of deal. Not yet, at least. He

starts to sidle past the dealer, saying, ‘It’s just that I’m not into industrial chemistry.’

‘Well, you think about it,’ the dealer says genially. ‘This here is a steady trade, and I hear the law is about to catch up

with the weird shit you make. But I can’t talk now, man, people be quitting work, hurrying over to get their fix. Later, eh?’

Past the elevated railway line is the back end of the dilapidated row of workshop units where Alex lives, half a dozen in

a row, overlooked by the gutted wreck of a toytown yellow brick office block dating from the eighties, its blue and red plastic

fittings faded and broken, every window smashed. Weeds push up through the tarmac of the access road; buddleia bushes have

established themselves on the flat roofs. The sharp smell of solvents from the chip-assembly shop at the far end. Frank, the old geezer who sells second-hand office furniture, is sitting in the sun on

a black leather swivel chair, and nods to Alex as he goes past. Alex thinks he’s exchanged about ten words with Frank, and

they’ve been neighbours for the last three months. On the other side, there’s the busy chorus of Malik Ali’s industrial sewing

machines: three of the units are used by Bangladeshis in the rag trade.

Alex has another bad moment when he ducks through the little access door set in the double doors that front his own unit –

someone could be waiting for him in the dark – but then he clicks on the fluorescent lights, and of course no one’s there.

He gets a quick shot of reassurance from a couple of tabs of Cool-Z, which he washes down with that day’s carton of Pisant,

this orange cinnamon drink he discovered in a vending arcade on the Tot-tenham Court Road. Pisant lasted about a week in the

frenzied sharkpool of niche marketing, probably because of the name, but Alex tracked down the supplier before it disappeared,

and the last of the world’s supply of Pisant is stacked in one of his three industrial fridges.

For the rest, there’s an extruded stainless steel kitchen, empty except for a big cappuccino machine and the microwave Alex

uses to heat up reconstituted Malaysian army rations – he has about a thousand unlabelled packs crated in the back of the

workshop – and the food he orders from the Hong Kong Gardens takeaway. There’s a bed in the back, too, behind a Chinese screen

of lacquered paper, and a little toilet and shower cubicle rigged up in what was once an office. The rest of the space is

taken up with lab benches littered with glassware, a containment hood, ultracentrifuge, freeze-drier and benchtop PCR, a second-hand

bioreactor, a metal-framed desk with the computer Alex uses for sequence modelling and for running his artificial life ecosystem,

and, in the middle of the bare concrete floor, the machine for which he sold his soul: Black Betty, a sleek state-of-the-art

Nuclear Chicago argon laser nucleotide sequencer and assembler.

The smell of the place, a potent cocktail of solvents edged with hydrochloric acid fumes, reassures Alex’s backbrain. He’s

been here three months now, and he still likes it. Black Betty is purring and clicking, the mini-Cray which controls her scrolling

through the assembly program a line at a time. She’s making another batch of the stuff he trashed at King’s Cross, but he doesn’t have

the heart to switch her off. Of course, he should never have bought her and put himself in hock to Billy Rock’s family, which

was the only place he could get the money. But what can he say? It was love at first sight.

Alex checks his mail, but there are no messages. His online daemon tells him it’s logged a couple of interesting discussion

threads, and asks if he wants a new database of chemical suppliers, but Alex tells it he’s busy. The daemon – a dapper red

devil with a forked tail and a pitchfork – knuckles its horned forehead and does a slow fade.

Right now Alex’s contact could be spilling his guts in some police station interview room, although since he has diplomatic

immunity he should be smart enough to say nothing even if it does incriminate him. Alex thinks about this, and knows he should

get out even if the guy doesn’t talk. But it isn’t as if he’s done anything illegal, and besides, he can’t leave his stuff.

The Cool-Z is working now, an icy sheath of calm closing around him. Alex does what he should have done at King’s Cross, if

he hadn’t panicked at the sight of the squad cars. He calls up Detective Sergeant Howard Perse.

Perse answers on the first ring, as if he’s been waiting for the call. He is sitting close to the camera of his phone, distorting

Alex’s view of his heavy, pockmarked face.

‘You look fucke

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...