- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

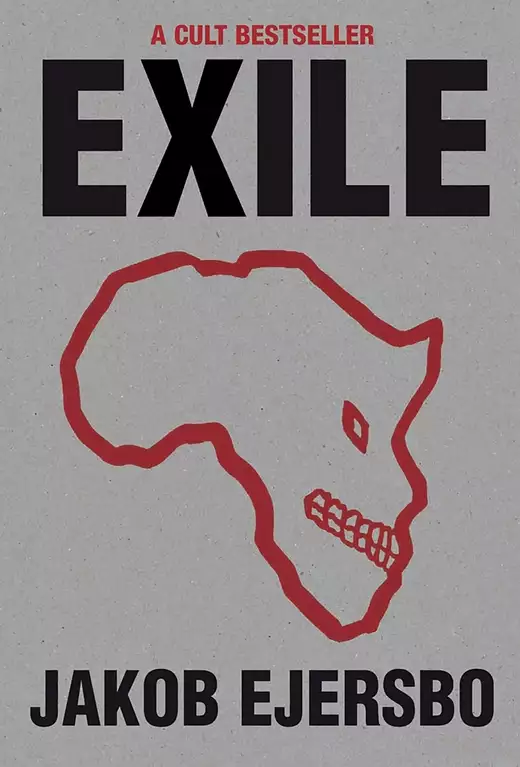

For the vagabond pack of ex-pat Europeans, Indian Tanzanians and wealthy Africans at Moshi's International School, it's all about getting high, getting drunk and getting laid. Their parents - drug dealers, mercenaries and farmers gone to seed - are too dead inside to give a damn. Outwardly free but empty at heart, privileged but out of place, these kids are lost, trapped in a land without hope. They can try to get out, but something will always drag them back - where can you go when you believe in nothing and belong to nowhere? Exile is the first of three powerful novels about growing up as an ex-pat in Tanzania. Ejersbo's first novel, Nordkraft, the Danish Trainspotting, was a phenomenal bestseller. Ejersbo's trilogy, only published after his death in 2008, has proved to be another cult and critical sensation.

Release date: October 27, 2011

Publisher: MacLehose Press

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Exile

Jakob Ejersbo

I head up the slope. Baobab Hotel is quiet – the main building with its reception and restaurant areas, the bungalows spread among the baobab trees. We don’t have a lot of guests. Inside the house Alison is packing. She is going to live with my dad’s sister and study hotel management for six months at a school in Manchester, and after that she is going to work as a trainee at a hotel. I lean against the door to her room.

“Are you going to leave me here alone with the folks?” I say.

“Yes,” Alison says.

“They’ll be the end of me,” I say.

“I have to get a qualification some time,” Alison says. Dad passes in the hall. I turn my head to watch him as he goes.

“I haven’t been to England for three years. We’ve lived here for twelve – I’ll end up a Tanzanian,” I say loudly. He continues down the hall.

“You’ll get to England soon enough,” he says without turning.

“I bloody well need to,” I say. Dad stops, looks at me.

“That’s enough from you,” he says. “I’ve told you not to swear at home. You can go and visit Alison next year.”

Mum serves lobster for dinner, and afterwards Alison makes crêpes suzettes, which she flambés in Cointreau at the table.

“The first bird to flee the nest, Mrs Richards,” Dad says to Mum.

“Yes. Sad, isn’t it?” Mum says and smiles – slightly tipsy.

Alison puts her arm around my shoulder.

“I hope they behave while I’m away,” she says.

I nod.

“Who?” Dad says.

“You two,” Alison says.

“Luckily I’ll be at school most of the time,” I say.

“We’re not that bad, are we?” Dad says. I pluck his cigarette out of his hand and take a drag.

“Samantha,” Mum says sharply.

“Oh, let the girl,” Dad says.

“She’s only fifteen,” Mum says.

“I did worse than that when I was fifteen,” Dad says.

“Yes, but we don’t want her to turn out like you, do we?” Alison tells Dad.

“Samantha’s a tough customer like her old man,” Dad says and looks at Mum. “The children are almost leaving home. Job well done. We can split up, then.”

“Dad,” Alison says.

“Why do you have to be such a boor?” Mum says.

“Tsk,” I say.

Mum starts snivelling.

I wake up early with blood on the sheet, a headache and aching joints. I can hear the maid in the kitchen. We have to leave by mid-morning. I scrunch up the bed linen and dump it in the laundry basket. Then it’s into the sitting room. Alison is standing in the middle of the room in an oversized T-shirt, looking sleepy.

“Where’s Dad?” she asks.

“I don’t know,” I say. I look outside – his Land Rover is gone. Only clues: toothbrush missing, toothpaste, gun. Not a word, not even a note. Just gone. How long? Who knows? Mum sits on the patio drinking coffee.

“He can’t face saying goodbye to Alison,” she says.

I leap down the slope and into the boathouse; then I sail out to fish, bringing only a mask, a snorkel and a harpoon. I hang about three metres below the surface, and it starts raining, even though the short rains aren’t due for several months – it’s scary. The surface of the water is whipped to foam. I hurry back ashore. Everything’s a grey blur.

Mum is still sitting on the patio. The rain has stopped.

“Don’t you have anything to do?” I ask.

“Why?” she asks.

“Because …” I say.

“You girls have almost left home, and Douglas is always away, and I have chased the staff every single day for years and told them the same things over and over. And they don’t do it – not unless I stand over them, glaring at them. I’m sick of it. I’m sick of the humidity, of the mosquitoes, of the hotel, of …”

“Of Douglas, of us,” I say. Mum looks startled.

“Not of you,” she says. Alison appears in the door leading into the sitting room.

“You’re sick of yourself, really,” she says.

“Yes,” Mum says. “And of Africa. Africa is doing me in.” She looks up at me. “If I went back to England, would you come, Samantha?” she asks.

“You want to go on holiday?” I ask.

“No, to stay.”

“In England?”

“Yes.”

“No,” I say. England? What would I do there?

“We have to be off soon,” Alison says.

The road west is shoddy almost all the way to Road Junction, and it takes us six hours to drive the 350 kilometres inland to Moshi where the school lies at the foot of Kilimanjaro. Fortunately there’s a couple of days left until the holiday is over, so we drive on for another hour westward, almost all the way to Arusha. It’s lovely to get inland after the humid heat of Tanga.

A couple of kilometres before we reach Arusha, we leave the tarmac road and head up the dirt track to the slopes of Mount Meru and Mountain Lodge. We’re visiting Mick, who is two years above me. Four months ago he fell ill and went to hospital right before sitting his exams. I’m looking forward to seeing him.

Mountain Lodge is an old German coffee farm dating back to 1911. It has been done up as a high-end hotel. Mick’s mother is running the lodge and a safari company with Mick’s brother and his wife. Mick’s stepfather has a travel agency in Arusha.

Mahmoud comes out and tells us that Mick is the only one home. The others have gone on a safari in Serengeti with some Japanese people. I had really been looking forward to seeing Mick’s sister-in-law, Sofie; she is so much fun. “But come in and have a cup of tea,” Mahmoud says and walks ahead of us in his Arabic get-up with a turban and a scimitar in his belt – anything for the tourists. Mahmoud is a dignified man; he rules the local staff with an iron fist. We follow him to the patio surrounding the large, whitewashed house. A thin man in a deckchair is staring at us.

“Mick?” Alison says. He smiles so broadly that the skin on his skull creases as he slowly gets up.

“Is that really you?” Mum says.

“It’s me, Mrs Richards,” Mick says. He looks like a dead man. We hug him and are careful not to hug too hard. “Don’t worry,” he says and presses me close. “I won’t break.”

“How much weight have you lost?” Alison asks.

“Sixteen kilos,” Mick says. “At first it was just the dengue fever: raging fever for a fortnight, a red rash all over my body, terrible muscle aches, internal bleeding. At the hospital in Arusha they had to try to bring down the fever with ice and plunk in an I.V. because I was so dehydrated.”

Mick lights a cigarette and smokes it slowly – even his fingers are thin. It’s a good job he was chubby before, otherwise he’d be six foot under by now.

“But with the I.V. came typhoid; I sweated, threw up, almost shat myself to death. The hospital was killing me. So Mum arranged to have me come home and hired a nurse to look after me.”

“It’s dangerous to be ill here,” Mum says and shakes her head. True. The corporate ex-pats are flown home if they fall ill. None of our parents can afford health insurance, but we know how to bribe the doctors.

“So, what now?” Alison asks.

“I have to do some retakes and then I’m off to Europe,” Mick says. “I don’t know where exactly.” Mick has a German passport because of his mother – I think she is really Austrian, but she used to be married to a German. Mick doesn’t speak any German, and his stepfather is French. His real dad was English, but he died years ago of some sort of malaria.

“Mind you come and visit if you do go to Europe,” Alison says.

“Oh, I’m going,” Mick says. Mahmoud brings out tea and cakes.

“I’m afraid we’ve no room for you,” Mick says. “We’re having a load of Japanese in tonight.”

“Oh, don’t worry,” Mum says. “We’ve arranged to stay at Arusha Game Sanctuary.”

All of us white ex-pats are old friends, and when we go around the country, we stay at each other’s. Arusha Game Sanctuary belongs to Angela’s family, who are Italian. Angela is two years above me, and I’ve known her since I was a little girl – she was in Mick’s year at the Greek school in Arusha until they came to the school at Moshi. But I’d rather stay at the lodge.

“How about you, Samantha?” Mick asks.

“I think I’ll be at Arusha Game Sanctuary until I go back to school. There’s not much point in going home to Tanga with Mum.”

“Come and see me,” Mick says. “We can always fit you in.”

After tea, we drive down to Arusha Game Sanctuary, which is run by Angela’s mum. It’s like Baobab Hotel, with a restaurant and bungalows for the guests. But they also have a little zoo with all sorts of creatures from birds to lions.

Angela is staying with friends in Arusha, but her mum is at home and gives us our rooms. She says that it’s no problem: I can stay with them until the new term starts. I go down the footpath with Alison to Hotel Tanzanite next door to swim, but it’s disgusting – too much chlorine in the water.

We sit, drinking Cokes, smoking cigarettes, not saying much.

“You’re upset – don’t be,” Alison says.

“You are too,” I say.

She nods.

The next morning we take Alison to the airport, which is halfway between Arusha and Moshi. I can tell from the way Mum looks that she had a few too many last night.

“I’ll talk to your dad,” she says. “Then we’ll see if me and Samantha can come see you for Christmas.”

“Yes,” Alison says, and then she says nothing for a while. It doesn’t seem likely that we’ll be able to afford any more airline tickets. There are swallows flying about inside the airport terminal. We say our goodbyes at the check-in counter. Mum is crying, Alison is gritting her teeth, I clear my voice and swallow.

“Now, don’t you go doing anything stupid while I’m away,” Alison whispers in my ear. She lets go of me and starts walking but turns around. “You will come up and wave, won’t you?” she asks in a small voice, and I swallow again, and Mum nods, and Alison disappears behind the doors. We take the stairs to the roof, which is used as a viewing platform.

“I’m going to miss her,” Mum says.

“Yes,” I say and light a cigarette.

“You shouldn’t smoke, Samantha,” Mum says.

“Right now I should,” I say.

“If you say so,” Mum says, and we wait in silence, staring at the passengers walking towards the plane until Alison comes out of the building below us.

“Bye now, Alison – take care,” Mum shouts.

“Take no prisoners; kill ’em all,” I shout. Alison doesn’t say anything – she kisses her fingers at us and waves and stops at the door to the plane, and a queue forms behind her while she looks up at us one last time. And then she’s gone. We stay there silently, trying to stare through the little windows of the plane to see her, but no such luck. Nevertheless we remain there, waving, while the plane taxies out. We wait as it rumbles down the single take-off and landing strip, turns around and gathers speed. We wave again as it takes off. We’ve flown from this airport several times. We know that you can see the people on the platform as the plane rises. We know that she is sitting there, looking for us and thinking about when she is going to be able to come back.

“Mum, you can just drop me off on the main road,” I say as we leave the airport, because Mum is going east while I am going over to Arusha Game Sanctuary to stay for two days until the new term starts.

“No, of course I’ll drive you.”

“I’ll just get a bus, Mum. That way you can be back in good time.”

“Alright then,” she says and hands me some money. “Remember to call home, Samantha.” I hug her and get out – then watch her drive off. I eat barbecued cassava with a mustard dressing at a wooden shack, drink tea. Then I get on a bus towards Arusha. I’m squashed between the Maasai girl on my lap and the goat between my ankles until I can get off at Arusha Game Sanctuary.

Angela is back. She is in their garden, working on her tan. I don’t really know her, although she’s quite cool and doesn’t take shit from anyone. When she went to the school at Arusha, she was a day pupil, and at the school at Moshi she’s in a different House from me. Angela is thin, gawky, small-boobed, hawk-nosed. Alison has always thought that Angela wasn’t “all there”. I walk up to her.

“Hey there, Angela,” I say. She lifts her sunglasses and looks at me. Her eyes are red-rimmed as if she’s been crying.

“Me and my mum had a row,” she says.

“What about?” I ask.

“She says I’ve been flirting with her boyfriend,” Angela says.

“And have you?” I ask.

“A bit.” She put her sunglasses back on. “He’s a big game hunter from Arusha. Italian.”

“And your mum’s boyfriend,” I say.

“For now. But it won’t last,” Angela says. What am I supposed to say to that?

“Do you want to go swimming?” I ask. She doesn’t, so I go alone. When I return, Angela has disappeared, and her mum doesn’t know where she is – she doesn’t seem to care either. I eat and go to bed and cry. I miss Alison. I wish I had gone home with Mum to Tanga. I don’t want to go back to school.

In the morning Angela is gone, so I tell her mum that I’m going to go up to Mountain Lodge to see Mick, and that I’ll get a bus from there to school the next day.

Mountain Lodge is only two kilometres down the main road and then a good stretch up the slopes of Mount Meru. It’s not so far I can’t walk, because it’s only morning, and the Arusha area is so high above sea-level that it’s still cool up there. I walk up to the lodge. Between the trees I see the garage where Mick keeps his Bultaco motorbikes and his beach buggy, which is resting on its flat tyres. In front of the lodge there is a small stream coming from the mountain, and right by the bridge there are reservoirs, trout ponds. Mick is standing there next to a worker who is fishing out rainbow trout with a net on a bamboo pole. Mick hasn’t seen me. He is shirtless, scrawny.

“Mick,” I call out. He looks up and smiles. Comes up to me on the bridge, gasping for air. He puts his arm around my shoulder.

“Will you help a sick man get home?” he asks.

“Of course,” I say.

“Alison – did she get off alright?”

“Yes. And Angela was at home, but … I don’t really know her,” I say.

“A bit of a wild one, she is,” he says.

“Maybe you fancy her,” I ask.

“No, I don’t like her,” Mick says. “Far too much dirty talk in that mouth of hers.” We reach the house. Mahmoud serves us lunch and tea on the patio. We smoke cigarettes. “I have to go lie down for a bit,” Mick says. “I’m still feeling a bit dodgy. But you can come along.” He winks at me.

“You’d like that, wouldn’t you?” I say and stay where I am.

“You will stay until tomorrow though, won’t you?” Mick asks. I nod. He goes inside. I walk around the garden. I am fifteen. Mick is seventeen. I haven’t lost my virginity. I go into the main building. The ground floor has a large room with an open fireplace and a dining room for the tourists, filled with trophies and furs. The family lives on the first floor. I go up the stairs. The door to Mick’s room is ajar. I walk over to it. “Come in,” Mick says, and I do. It’s very gentle, very sweet. I get goose bumps when Mick undresses me. We go slow until Mick uses his hands and his tongue on the special spot, and then it’s more than just sweet. He raises his head and looks at me. “The pearly gates,” he says.

First day at school. At 7.30 I dash out of my house, Kiongozi House, towards the dining hall. The boarders live in houses according to their age and sex. Some of them are quite some way from the school, but Kiongozi House is placed right next to the playground where the younger pupils play. I always arrive at the last minute – hair tousled and books under my arm – giving myself fifteen minutes to shovel down the grub.

“How are things, Samantha?” Shakila is already leaving the dining hall. She is the daughter of a professor who runs a private hospital in Dar. Shakila is two years above me – she was my “mentor” when I was sent to boarding school at Arusha in Year Four. All the new pupils are teamed up with an older pupil who is supposed to show them the ropes, teach them how to make their beds, tidy up, do their prep. Shakila was mine, and even though it’s been four years, she still sometimes asks how I’m doing.

“Good. And you?” I say.

“Good,” she says. Why is she asking? Because Alison has gone. I’ll be alone at school from now on. For the first time I have neither my parents nor Alison around. The dining hall is half-empty – the older boys are in Kijito House and the girls in Kilele and Kipepeo Houses have their own kitchen for breakfast, while the oldest of the boys in Kijana House and the ones from Kishari House eat at school.

I spot Panos, who is sitting at a table with Tazim, Truddi and Gretchen, who I share a study with. We’re all starting Year Eight today. Panos is polishing off bread and juice – he is a mulatto, and his dad is a Greek tobacco farmer in Iringa. Out of the corner of my eye I see Jarno from Finland staring at me with his piss-coloured eyes behind the pale dread-locks he has started sporting.

“Are you alright, Samantha?” Tazim asks.

“Of course she’s alright,” Panos says. “She’s eating, isn’t she?” I’ve known Panos for seven years, ever since I started school in Arusha in 1976 – Year Four, when Alison was in Year Seven. Panos is as strong as a horse, barrel-shaped, with a fervent hatred of books. We have to be out of the dining hall by 7.45 – the first lesson starts at 8.00. “Cigarette?” Panos asks without looking at me, as he gets up and scans the room.

“Absolutely,” I mumble through the food in my mouth.

“At Owen’s,” he says and leaves. Owen is the Headmaster and his house is right behind the dining hall. It was Panos’ idea to smoke right behind his house because that’s the one place no-one will look for offenders. And Owen is already at the office – his wife has gone down to the teachers’ common room. I sprint out after Panos, flitting between trees while I look up at Kilimanjaro. The snowcap on Kibo’s peak is still visible – it won’t be covered by clouds until some time in the mid-morning when the sun makes the water evaporate from the rainforest further down the mountain. I’ve never been up there, even though you can climb the mountain with school – I just can’t be bothered. But Panos has, even though he was sick repeatedly on the way to Gilman’s Point and didn’t make the trip round the edge of the crater to the highest point, Uhuru Peak. Before the first white people climbed the mountain, the Africans believed that the white crown was made of silver.

Panos has stopped in the dense bushes behind Owen’s house.

“Are you alright?” he asks.

“I hate being here,” I say.

“Tell me about it.” We light up, smoke so fast it makes us dizzy, share a piece of Big-G gum to cover up the smell, trot down to our classrooms; it’s 7.55 now. The entire area is swamped with infants – day pupils. I.S.M., that’s the name of the school – International School of Moshi. It offers twelve years, and then you’re ready for university.

The day pupils know nothing about life. Home every afternoon to have their bottoms wiped by Mummy and Daddy. Most of the boarders are white – children of diplomats or people who work for aid organizations, or families who run farms or tourist businesses in Tanzania. And then there are the black boarders – sons and daughters of corrupt businessmen or politicians. Among the day pupils are a lot of Indians. The school started out as a Christian school when a group of whites built the large hospital K.C.M.C. – Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre, which is reportedly the best hospital in the country. There are still plenty of teachers who are holier than thou, but there are also loads of Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims, and at least you don’t have to wear a uniform here the way you did in Arusha.

The first lesson starts. Another day of our lives is about to be wasted.

Everyone is running around saying hello to each other in break time that first day. I look for Panos’ friend, Christian, but he’s not in school. Christian lives at the sugar plantation T.P.C. just south of Moshi. Almost a year ago his little sister died in a traffic accident – maybe his family have gone home. For a while afterwards he went out with Shakila, but it didn’t work out, and he was suspended for a week for constantly smoking cigarettes everywhere.

Savio comes over in the lunch break and asks about Mick. It makes me feel all warm inside, just hearing his name. Savio is thickset, originally from Goa, now from Arusha, and a Catholic.

“He’ll be here soon for his retakes,” I say.

“Is that you, Mick?” Savio says and looks over my shoulder. I turn around. Mick is coming down the corridor.

“Savio, my man,” he says. “Samantha.”

“Christ, you’re thin,” Savio says and slaps his hand. Savio stands shoulder to shoulder with him and lifts up his T-shirt. Savio is pot-bellied and Mick is worn to a shadow. We laugh. Shakila comes running and hugs Mick. They went out for a while last year before he fell ill.

“You’re back,” Shakila says. At the same time Tazim is standing some way off, looking sad – she fooled around with Mick once, but nothing came of it.

“I’m not back,” Mick says. I swallow.

“What’s going on?” Savio says.

“They can’t be bothered set up a retake for me until November. Actually they’d rather I retook Year Ten,” Mick says.

“Bastards,” Savio says.

“What are you going to do?” I ask.

“I’m getting out of here,” Mick says.

“And going where?” Savio asks.

“Germany,” Mick says.

“What are you going to do there?” I ask.

“I know a German bloke who is signing up for a Technical School in Cologne, but it’ll be me showing up with my friend’s exam papers.”

“Cool,” Savio says.

“What are you going to live on?”

“I have a small inheritance from my Austrian grandmother, and then I mean to buy used cars, do them up and sell them at a profit,” he says. Mick has been taking motorbikes apart since long before he could ride one. And he does it the African way – with whatever is to hand.

“But do you speak any German?” I ask.

“Enough to have a German passport,” Mick says and laughs. “I can order two beers.” Aziz comes over – a greasy Indian from Mick and Savio’s year.

“Do you have any Arusha-bhangi on you?” Aziz whispers to Mick – Aziz smokes far too much weed.

“No,” Mick says.

“Come on, be a chum, Mick. I know you’ve got some,” Aziz says. He is always trying to make some deal or other.

“Piss off,” Mick says. I wish he’d just kiss me.

Lesson after lesson. I drag my bag behind me as I leave the classroom and cross the concrete decking stretching along the classrooms under the eaves of the roof that stops us having to wade in mud during the long rains.

“Samantha,” Mr Harrison says behind me. I stop, standing still without turning around and without answering. “You should carry that bag properly.” I turn around slowly.

“How do you carry it properly?” I ask.

“Pick it up,” Mr Harrison says.

“That’s for me to decide. It’s my bag,” I say.

“But it’s the school’s books,” Mr Harrison says.

“Are you sure?” I ask.

“Do you actually want to be sent to the Headmaster?” Mr Harrison asks. I shrug. What else can I do? Lose face? I’m standing still, waiting. Quite a few people are now watching us. Then Mr Harrison starts smiling. He comes over to me, takes the strap out of my hand and lifts it over my head, taking my arm and moving it, so that it rests on the bag, which is now hanging with the strap between my breasts. “There you are,” Mr Harrison says and pats me on the shoulder before he hurries towards the teachers’ common room without looking back. I stay where I am for a moment. Then I grab hold of the strap, lift it over my head and lower the bag onto the concrete decking.

“Samantha,” Gretchen says, shaking her head.

“Would you carry a mangy dog like that?” I ask and start walking again, dragging the bag behind me. The bag is jerked – Svein is giving it a hard kick, making it lift off and fly into the wall. The strap is still in my hand.

“Idiot,” I say, swinging the bag forward sharply. Svein jumps out of the way, making me miss my mark, but I bulldoze on and let the bag swing a full circle over my head until it slams into the back of Svein’s.

“Samantha!” That’s Mr Thompson’s voice – he’s the Deputy Head. Everyone stops in their tracks. I turn my head and look. “My office, now,” Thompson says, jerking his head. “You too, Svein.” Svein protests. I shrug and head towards Thompson’s office. The bag is trailing along the concrete decking behind me.

I bump into Stefano at running practice. Some of us girls are standing waiting for the runners to come back from their ten kilometre run. Me and my study mates – Tazim, who is from Goa, vivacious and sweet, and Norwegian Truddi, who is standing with her friend Diana, the daughter of a corrupt Member of Parliament who people have named Mr Ten Percent.

Italian Stefano is first man back, blasting into the far side of the playing fields, encircled by 400 metres of running track. All he needs to do now is cross the finish line. We cheer him on. Baltazar comes into view only a short distance behind Stefano. Baltazar is tall and black as coal, the son of the commercial attaché for Angola. Stefano is short and powerfully built, topless … No, he’s just pulled his head out of the T-shirt and pushed the front of it behind his head; it covers the back of his neck so he doesn’t get sunburned. I can see how the muscles on his chest and stomach shift; there isn’t an ounce of fat on him. His upper body glistens with sweat. He looks over his shoulder, allows Baltazar to catch up a bit but keeps a distance of a couple of metres. Stefano reaches the finish line first, arms in the air. Dark hair is visible in his armpits. The cross in his silver necklace has been stuck to his chest with tape so it won’t jitter about when he is running.

“God, he is so dishy,” Truddi says next to me. Stefano comes over to us spectators.

“Hi, Samantha,” he says.

“Hi,” I say. He comes up close and takes my hand, lifting it.

“Can you peel this tape off for me?” he asks.

“Of course,” I say and, taking a careful hold of one corner and feeling the warmth of his skin, I pull it off.

“Thanks,” Stefano says.

“Why don’t you just take it off when you go running?” I ask.

“My mum gave it to me when I was born,” he says. And I think that’s the most beautiful thing I’ve ever heard.

T. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...