- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

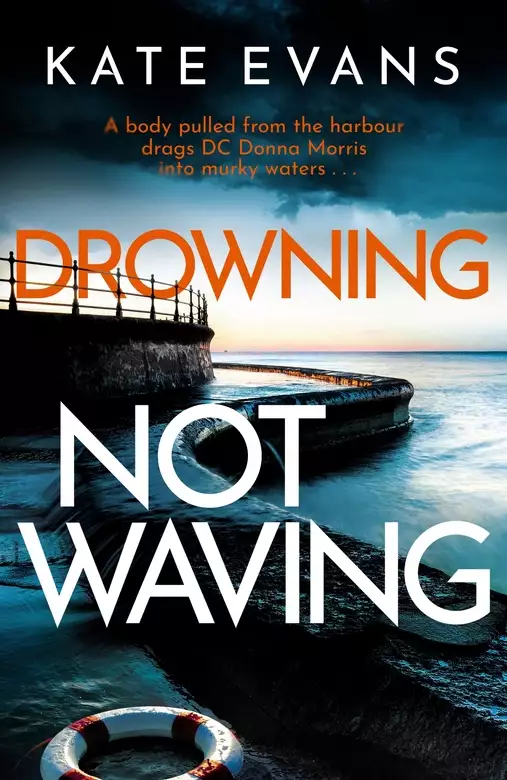

A body pulled from the harbour drags DC Donna Morris into murky waters...

The lives of the people of Scarborough have always been tied to the sea. Often their deaths too. And when the body of a young man is pulled from the harbour, the police investigation has to dive into the tightly knit fishing community there. But DC Donna Morris, halfway through her probationary period in the town, finds very little is at it seems.

Is the killing to do with old rivalries or more contemporary enmities, or is it somehow linked with a shocking murder which took place in the town twenty years ago? Donna does her best to navigate the tides and currents of the place she calls home for now, but finds people are prepared to muddy the truth if it means preserving the past, and old reputations.

Release date: June 9, 2022

Publisher: Little, Brown Book Group

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Drowning Not Waving

Kate Evans

At his full height, he’s a good fifteen centimetres taller than her, and he’s muscular.

Prides himself on those biceps, she thinks sourly. Then, briefly, wonders at the damage his fists could do to her, before she sends those thoughts packing. He wouldn’t hurt me. Not in that way. The problem is his words can be equally crushing.

‘We can’t afford to do nothing,’ he says pompously. ‘We’re in a crisis. People are dying.’

Like I don’t know! Like it’s my fault! Like I’m not doing my best! The phrases she wants to throw at him get all mixed up and clogged in her throat; nothing but a strange strangulated screech escapes. She is beyond arguing. There’s no point, she tells herself. He is beyond listening. She wants to pound that self-satisfied chest until he sees her point of view. Until he apologises, for, for being so bloody minded, so bloody mean. ‘I thought you were my friend,’ she shouts. Ridiculously, she knows.

‘What’s that got to do with it? I thought you had some backbone.’ He turns abruptly and walks the short distance to the door of her flat.

Once he has snapped it shut behind him, she yells, ‘Fuck you, Orson Reed!’

Fifty-nine hours later, five hours into her shift, Alice hopes Orson has abandoned his plan. How wrong she is.

She was in charge of the set-up and is now coordinating the service. People had started arriving at seven-thirty on the dot. They are dressed as if they are on some fancy cruise around the Caribbean, not at a party four days into January on the North Yorkshire coast. It has been a long time since Alice has seen quite so many flashy jewels and furs – even if they are mostly fake.

The rowdier mob arrives around ten p.m., already tanked up. Alice has another go at pulling up the plunging neckline on her uniform and at pulling down the skirt. As she passes through the crowd, male hands ‘inadvertently’ stroke her bosom or land on her bum. One set in particular. She has to sashay her way around him. And he is everywhere she is. A gnome in an extravagant cravat. She does another sidle, bangs her tray down on the bar and says she needs to pee. The staff toilets are down a narrow corridor. At least they are as new as the rest of the venue. She takes her time, using one of the fluffy hand towels to cool her face and neck before discarding it in the basket provided. Perhaps Orson was correct, she is a traitor to the cause. She promises herself she won’t do another gig like this one. Knowing she will. The money is too good to turn down.

As soon as she exits the corridor, she is aware that something untoward is happening. The hot air is as stretched as stale toffee. The chatter has died down. Everyone is looking towards the middle of the main room. Some are craning over others and asking what’s going on. Firmly corralled to the rear wall, Alice finds a low coffee table to stand on.

Orson is addressing the assembly as if he has been invited to do so: ‘Each one of you is killing the planet with your excess and your ignorance. You are sweeping the crisis under the carpet because it suits your pockets and it is not you who are suffering. Not yet.’ He is dressed in his khaki combat trousers and grey hoodie and is carrying two wooden boxes, stencilled with the words: ‘Moët & Chandon Jeroboam’. He must have fashioned them himself, Alice concludes. There is no way he would have purchased them. She can also see he has his bodycam attached to his top. He is filming it all, either for live streaming or for later release.

By now, several people are beginning to work out that Orson is not the delivery man they took him for. There are movements forward to stop him and to get the security guards to eject him. Sensing this, Orson quickly flicks open one of the boxes. It is full of rotting fish. He lets them tumble to the floor. The smell hits everyone in their craw. Some retreat from it, others turn away, hands to mouths, greening at the gills. Then Orson catches sight of someone. He launches forwards with the other box, shouting, ‘This is for you, you bastard. Don’t you worry, I’ve got enough to bring you down.’

His sudden movement brings animation to others. A large man with a dark thatch threaded with grey grabs at Orson’s arms. Though the effort brings a deluge of blood to the man’s face and almost causes an apoplexy, Orson’s progress is slowed enough for him not to reach his cravat-wearing target before the burly security guards appear. Through the hubbub which ensues, Alice gathers there is a discussion over whether Orson should be arrested. She breathes out when she realises his erstwhile victim has vetoed the idea and, instead, Orson is marched off the premises, his second box intact.

Alice wants to follow, to make sure he is all right. Instead, her boss for the evening appears with cleaning equipment and Alice is set to sorting out the rotting fish with another colleague. Thanks Orson, Alice thinks as she shovels putrid mess into plastic bags and scrubs the carpet.

People, the more sober and more offended, leave. Others stay and Orson’s exploits get twisted to emphasise the bravery of those who stopped him.

In a spare moment, Alice slips onto the balcony. The cold midnight air scours her out. It is damp and foggy; she can hardly see to the harbour. Orson is not within view. Her concern for him is tempered by her crossness. As usual, he did not consider who would be (literally this time) cleaning up the mess he had made. And somewhere in there is the guilt: he did what she felt she could not. Maybe he is right. No backbone. She calms her helter-skelter thoughts. At least he is on his way home now. He will be pleased with himself and his footage. He may not have changed minds at the party. In any case that would not have been his aim. No, he will get the response he wants from his own framing on social media. He will cause outrage.

DC Donna Morris climbs the steps to the paved top of the harbour wall. It is a curved limb, sheltering on one side yachts and an assortment of in-shore motor boats. Donna faces the other way. It is the first Tuesday in January 2014. It is the hour presaging dawn. The opposite of dusk, thinks Donna. She cannot wrangle out a term for it. Perhaps there isn’t one. Der Morgenstunde: the German comes to her quicker than it has done in years.

The sky is turning from charcoal to ash, as if the fine rain is dousing any effort of the sun to set the horizon alight. A pace from where she is standing, the edge of the wall is a steep drop, sharp rock armour crowding around at its base. The sea is a heaving reflector for the sky. From the jagged water, oarweed raises its broad fronds in greeting, a chorus of slick brown hands. For a moment, the swaying gives Donna the impression that it is she who is adrift and about to topple. She clenches her hands in her pockets holding tight to an imaginary rail. She knows someone has tumbled over. One of those waving kelp leaves had turned out to be all too human.

Resolutely she turns to walk down the centre of the harbour arm. She can see there is activity at the wrist. A large light has been erected and there are two figures illuminated in its glare. As she approaches, one of them, a young PC, comes over. He is familiar. However, after only four and a bit months as a probationer with the Scarborough force, she can’t put a name to the face. He obviously knows who she is. He is eager to update her. Donna remembers this eagerness from when she started in uniform. Ten years ago. She’d begun later than this youngster, after having children and several years as a Special. It’s not as if the eagerness wears off – Donna still greets every work day with enthusiasm (well most of them anyway). It is merely that it becomes tempered by the knowledge: a dead body creates its own swell.

‘Micky Harleson, thirty-seven years of age, found the body.’ The PC is reading from his notes. Despite his local accent, he can’t be that local or he would know the Harleson family as having fished in this sea for generations. The current owner of the boat catches lobster and crab. He was coming in after checking his pots when he noticed a marker buoy for a fellow fisher family’s pots had come loose and was bobbing around by the harbour wall. Attempting to retrieve it brought him into this field of oarweed. The PC indicates to his right with his pen. Donna glances over. The imperceptible lightening of the sky is giving everything more definition. But, as if in opposition, the tide is rising, gobbing up onto the walkway, and engulfing the bobbing heads of the seaweed. ‘He’d almost run over the body before he realised it was there. He called the inshore lifeboat and they pulled it out.’

‘Him,’ says Donna quietly, automatically.

‘Him, yes. They took it, him, to the lifeboat station and from there he has gone to the mortuary. He’s described as male, anywhere between late thirties and early fifties, quite well built, of average height.’

‘Stab wounds,’ Donna prompts. ‘Somebody noticed stab wounds?’

The PC nods. ‘The coxswain.’ He pronounces it smoothly, correctly. You can’t be five minutes in the town without learning how to get your tongue round coxswain. ‘Thought one in the side. He can’t be certain, he said, the body has been bashed about a lot and probably been a good supper for some of the wildlife out there.’ He looks over his shoulder and for the first time loses a modicum of composure.

Donna lets her eyes follow his gaze. On a morning like this it is easy to believe in sea monsters.

The PC turns and adds quickly, ‘That’s what he said.’ So it is the coxswain’s lack of sensitivity, not his own.

‘Good work,’ says Donna, rousing herself from thoughts of Leviathan and colossal squids. ‘The damage to him probably means he was in the sea for several days.’

‘The coxswain thought maybe since Friday or Saturday. Any longer and there’d be even less of him.’ Then he dives back into his notebook. ‘The body, ah, he was wearing a Gansey. They’re the pullovers knitted up and down the coast—’

‘Yes, each place has its own design, so the drowned can be identified. Was it a Scarborough one?’

He nods.

‘But Harleson and the lifeboat crew didn’t recognise our guy?’

He shakes his head. ‘Harleson didn’t see him and, as I said, the face was apparently very damaged.’

‘No ID?’

‘None that the coxswain could find.’

‘Probably at the bottom in there by now.’ Donna inclines her head to the sea. She can hear its swooshing and farr-umphing onto the rock armour. It sends a tremor through the concrete spit she is standing on and into her feet. ‘Thanks.’ She begins to walk towards the other figure in the lamplight, Ethan Buckle, the crime scene manager.

‘Erm, DC Morris, can I go now? It’s the end of my shift.’

Donna pauses. Is it for her to say or should she leave the decision to DS Harrie Shilling, whom she has called and is on her way? She looks back at the PC; all at once he appears rather vulnerable. Younger than my daughter and son, she thinks. Having to deal with too much for his years. She wonders what her DI, Theo Akande, would do. Over the months she has found this a useful guide. She smiles. ‘I’ll just have a word with Ethan and then probably yes.’ She doesn’t add that it’s the end of her shift too. She feels suddenly weary. But she will stay to hand over to Harrie and do whatever is required. ‘Meanwhile, keep your eyes stripped.’ She sees his look of incomprehension. It’s peeled, she remembers. She adds by way of explanation, ‘Make sure we are not disturbed.’

With the approach of day, some hardy types are out for their morning constitutionals, most with dogs, some running. The big glaring light is garnering interest. The PC tucks his notebook away and pulls his jacket up around his ears. The wind is sharp. The rain is still falling. Even so, he grins again and nods.

Donna reaches Ethan as he is putting away his camera. ‘Is this our crime scene?’ she asks.

‘Your guess is as good as mine.’ He is squat, shorter than Donna, and wider. Ex-military. In his late forties, he is a tad younger than Donna, though he hardly looks it with his pale bald pate this morning covered by a woollen hat. ‘He was found down there, but whether he went in from here is debatable. Knowing how long he was in the sea and the tides and currents over that time might give us a clue. I’ve had a good scan of the walkway and not found anything of particular interest.’

‘No pool of blood, for instance.’

Ethan returns her smile. ‘Unfortunately not, DC Morris. Anyway, over the weekend there’s been plenty of public traipsing through, not to mention the wet weather and overtopping. All adds up to an unacceptable level of contamination even if this is where our poor chap met his end.’

As if to prove his point, a wave slams into the base of the wall spitting up a spray of salt water to mingle with the drizzle already splattering their jackets.

Ethan picks up his camera case. ‘I think it might be time to leave.’

Donna feels reluctant: it would be inadequate for ‘our guy’ if she doesn’t probe further. ‘Murder weapon?’

‘Not that we’ve found. And if we go searching down there’ – he nods towards the rock armour – ‘we’ll need a specialist team.’

He calls for the PC to help him with the light. Donna tells the youngster he can get off once he has completed the log at the police station. The two men retreat quickly along the narrow catwalk towards the town, people, traffic and, no doubt, a hot beverage of some sort.

Before she follows her colleagues, Donna takes one more look around. The sky and sea are now both pigeon-grey, with dark curtains of rain being pulled across by the stiffening easterly. Herring gulls, their wings spread, ride the wind, seemingly enjoying the rollercoaster, occasionally screeching to each other. A short walk away, behind her, Donna knows there are cafés and shops. Even so, she concludes to herself, this is a cold place to die.

‘Have we got enough glasses?’ ‘Have we got enough wine?’ ‘What about juice?’ Wanda Buckle, the curator of the art gallery, is fussing. Alice Millson does not let it intrude on her calm as she carefully continues to set up her refreshments station. She is not surprised Wanda is practically having kittens. This photographic exhibition is a coup, Sebastian Hound’s first since he emerged from his self-imposed seclusion. ‘You’ll be ready?’ Wanda’s voice has taken on a higher-pitched twitter. ‘We’ll be opening the doors in just under ten minutes.’

Alice looks up and grins. ‘I am ready, Wanda. I was born ready.’

Wanda responds with an uncertain curving of the lips. However, Alice’s reassuring expression is obviously enough as she moves away and flaps around the two meeters and greeters on the door.

Alice knows she gives off the air of being flaky. She still treasures the comment: ‘So laid back as to be almost horizontal’, from one of her sixth-form teachers over fifteen years ago now. Yet, in reality, she is rather good at organisation and time management. She completes the trays with fancy hors d’oeuvres which she and two colleagues will take turns in circulating, just as the man himself arrives, fashionably cutting it very fine indeed.

These days Sebastian Hound is a humble type. He’d found notoriety young and had squandered it, been arrogant, forgot fame is fickle and talent no guarantee of continued, or any, success. In recent years he has become sober. Without his coterie of acolytes around him, he could have been taken for a rather shy gallery assistant or a benign fatherly figure smartened up for someone else’s festivities. He has his overcoat taken off him and assures Wanda several times that he is in perfect health and the drive over was just fine. Then he begins to warmly greet the staff and volunteers milling around. He reaches Alice, grasping her small hand in his ample paws. As he accepts an orange juice from her, she feels the graze of his electric-blue gaze over the length of her torso. Rumours of him having a liking for buxom women – or any women, as long as they are in their twenties – have not been exaggerated, she thinks. Neither her smile nor her fingers waver as she hands over the glass, but she’ll give a brief warning to her younger co-workers. At least for this gig they don’t have to wear silly-length skirts and skimpy tops. Not like at Saturday’s party – frou-frou costumes comedy French maids would be proud of. A nun would be comfortable in the calf-length dress Alice is wearing. Burgundy to match the tips of her dark hair bobbed to rim her round face.

The gallery was once the fine summer abode of the aristocracy. Its large entrance hall is two storeys high with a black and white chequerboard tiled floor. At the level of the first floor is a balcony on its four sides. Below this, Alice is standing in front of the hall’s ornate Carrara marble mantelpiece. Once the doors are opened, the place becomes thronged and Alice is occupied with making sure people have glasses which are periodically replenished and are being offered the plates of hors d’oeuvres. At the height of the preview, the noise in the hall is tremendous, voices and heels on tiles ricocheting up to the roof. After the speeches, when the crowd begins to thin slightly, Alice takes the opportunity to escape up the wide staircase with a basket to collect any abandoned glasses. There are several. If she were to see them, Wanda would get twitchy about the possibility of an accident resulting in broken glass too near the artwork. Alice quickly gathers them up. There are a few people up here, but it is altogether quieter and less frenetic. Alice pauses to take in some of the exhibition. She will come back, probably more than once, to study the technique. For all his failings, Sebastian Hound has a talent which Alice is keen to learn from.

Hound was barely twenty-one when he made his name in the mid-1990s. He started out with taking stark black and white photos of people caught off guard and landscapes in the throes of decay. His reputation detonated when he began to talk his way into select parties and it was celebrities who appeared in unposed awkwardness. His downfall came when his craving to be part of the in-crowd extended beyond his need to make art and when he added colour to his repertoire. In this exhibition he’s back to monochrome, to stark clean lines, making the ordinary extraordinary. On the balcony, Alice leans in to examine more closely a collection of images taken in a market: butchers alongside fishmongers, greengrocers and booths hung with bags and underwear. The stallholder or customer often caught staring into the lens, challenging and challenged at the same time.

For a moment, she is so engrossed, she does not notice the woman standing just to the side of her. Alice’s attention is drawn when the woman emits a strangled little whimper. She is tall – then most people appear tall to Alice – and stately, her ash-blonde hair in a large clip caught up severely away from her angular face. She has a long-fingered hand clamped over her mouth. She looks like she could be about to throw up. Wanda would not like that.

‘Are you OK?’ asks Alice. Maybe the hor d’oeuvres were less than fresh? She takes a step towards her. ‘Can I help in any way?’

‘What?’ The woman turns to her, more surprised, or even afraid, than sickly.

Alice is relieved. ‘You, you seem upset. I wonder if there is anything I can do to help?’

‘I, er, I, this photo – it reminds me of someone.’

Alice looks at it. The image is dominated by the Humber Bridge. The woman is pointing at a small figure edging out of the frame. The body is made androgynous by a heavy formless jacket. The face is out of focus. The woman’s fingers are now practically on the canvas, either to stroke the figure or maybe to scratch it out.

‘I don’t think you are supposed to touch,’ says Alice, though gently. She can sense the strength of emotion coming off the woman.

This snaps her into action. She says sharply: ‘Where’s the photographer? Where’s Sebastian Hound?’

‘Downstairs, I think,’ says Alice.

The woman marches off and Alice grabs her basket to scurry after. She halts, watching Wanda and Sebastian meet the woman at the turn of the stair. Wanda starts doing the introductions, ‘Sarah Franklande of ScarTek.’

ScarTek? Alice puts her basket down. Now she’s definitely interested.

Wanda continues with less assurance: ‘We’ve been so lucky to get funding for this exhibition from ScarTek. Leonard Arch, the owner, you’ve probably heard of him …’

The grabber of arses Saturday night. The night was really one to forget, for more reasons than Alice is prepared to consider fully. Even so, her cheeks burn at the flitting memory before she quashes it.

‘Sarah facilitated …’ Wanda flounders in the face of Sarah’s angry features.

Sarah Franklande fills the void: ‘Where is she? Where is Sylvia?’

Sebastian Hound smiles warily. ‘I’m sorry?’

‘The photo up there, with the Humber Bridge.’ Sarah’s words are distinct; she points upwards to the first floor gallery. ‘Is Sylvia your model?’

The man remains cautious. ‘I don’t use models.’

‘She’s in one of the photos you took, the one of the Humber Bridge. Please.’ Sarah’s voice crumbles. ‘If you know she’s alive, tell me.’

‘I’m sorry, I don’t know who you mean. I don’t pre-plan these things, they just materialise.’ He holds his forearms up as if being threatened with a gun.

The people downstairs have gone quiet, captivated by the kerfuffle on the staircase. Now it looks like it might be Wanda who is sick. Then one of Sebastian Hound’s companions, perhaps his agent from the luxury skirt suit and high heels she is sporting, approaches the trio. She takes Hound’s arm and peels him away, murmuring something about an interview. Wanda gratefully follows them as they pad down the stairs. The audience below loses interest and conversations start up again. Only Sarah is left, stranded, it seems, on the turn of the stair. She puts a hand out to the broad banister. Alice notices it trembles.

She goes down to Sarah, giving a quick scan of the more than half-empty hallway. Her colleagues can be left to cope. She makes a decision. ‘You OK?’ she asks, touching the other woman’s arm, which is holding her steady.

‘I’m fine.’ Sarah snatches her arm away, clutching it with the other one across her stomach. She juts her chin and nose up into the air.

‘Well you don’t seem fine. Maybe you’d like to sit somewhere, have a chat. I’m a good listener.’

‘I have to go.’ And she does, walking quickly but jerkily down the stairs, across the hallway and out the door.

‘Your coat …’ Alice calls. Sarah must have had a coat on an evening like this.

She does not appear to hear; she keeps on going. The door shuts behind her. Alice hurries down to the refreshment table to check she is not needed, then goes to the cloakroom and, with the help of the volunteer staffing it, retrieves Sarah’s coat. A top-quality wool coat, flared from the shoulder, the colour of camel hair.

Outside is perishing, especially when compared to inside the building. Alice hesitates, thinking she should get her own jacket. No time, she tells herself. She steps out of the ring of brightness thrown by the lights from the art gallery and looks around. No one is moving. There is no sound from a car. Probably she’s already gone. Even so, to be sure, she wanders over the road and up the steps into Crescent Gardens, from where she can see the street curving round to form its loop before exiting to the main road. Sarah is sitting on a bench, hunched over. When Alice approaches she can hear Sarah sniffling; she is wiping her cheeks and nose with her fingers.

‘I brought your coat,’ says Alice, sitting down. ‘And I have tissues.’ She offers them.

Sarah takes one and blows her nose. She also puts on her coat.

‘Who is Sylvia?’

‘You heard?’ Sarah breathes hard. ‘You’re not from around here or you wouldn’t have to ask.’

‘No, I am not. And I am asking.’ Alice knows she has to go slowly for her plan to work. She doesn’t mind, she is truly interested. Other people’s stories, particularly tragic ones, always pique her curiosity. ‘Do you want to tell me about her?’

‘No. I don’t even know you.’

‘My name is Alice Millson. Sometimes talking to a stranger can help.’

‘No,’ Sarah repeats crossly. She blows her nose again vigorously and turns towards Alice. Then something arrests what she was intending on doing or saying next.

Alice feels it too. Unexpectedly, a connection. She leans against the bench. They are sitting below a wide-spreading copper beech. Leafless, yet forming a canopy. A smudgy creamy curve is caught in the top branches. The moon is momentarily revealed through a crack in the clouds. How romantic. Alice tames her smile. She has a job to do.

However, Sarah is moving towards getting up. ‘Thank you,’ she says stiffly. ‘Thank you for getting my coat. For the tissues.’

‘Will you be all right?’ asks Alice, realising she is genuinely concerned.

‘I’ll be fine. I have my car parked over there.’ She is on the verge of leaving. She does not leave. She says, more quietly: ‘I made a fool of myself, in there. It wasn’t Sylvia in the photo. She died twenty years ago. I just wanted it to be her.’ She lets out a heavy sigh. ‘It’s the season, I guess, the season for remembering losses.’

It is rather more poetic than Alice expected. ‘I’m sorry,’ she manages to croak.

Sarah stands. ‘I must go.’

Alice notices Sarah’s mouth is a smidge large for her face and lopsided. It now slips into a rather cute smile. Alice realises she is going to miss this opportunity if she is not careful. She shakes herself to say quickly, ‘Yes, I must get back anyway, shoo ou. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...