Dreamland

- eBook

- Paperback

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

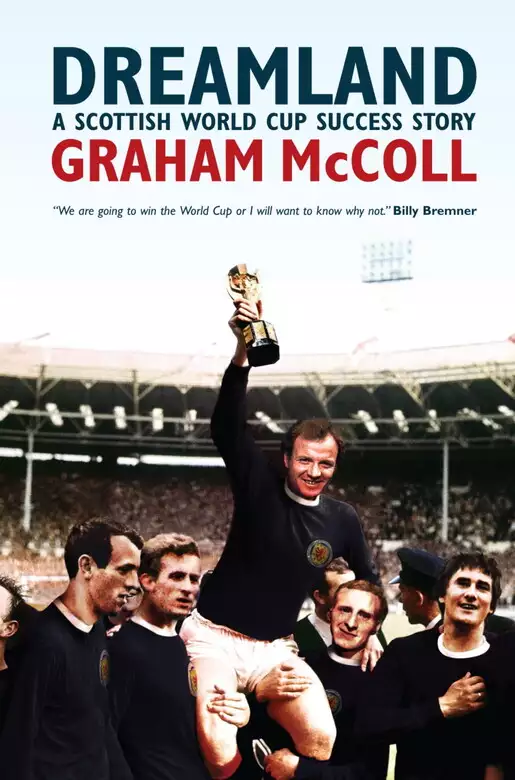

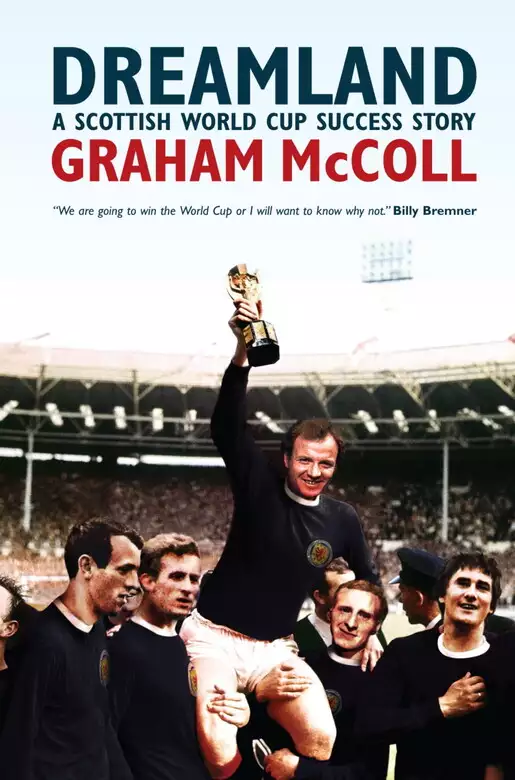

We had a dream... From Gretna Green to John O'Groats, wild celebrations ensue for the following week. Rubbish is not collected; post isn't delivered; trains and buses don't run; grass remains uncut at the height of summer; fish is not landed at the harbours. Nobody cares. It is as if everyone's birthdays have all come at once; as if two-dozen new years had been rolled into one; as if Scotland had beaten England 6-2 in the final of the World Cup at Wembley Stadium... The natural home for the World Cup trophy is in Scotland. Every Scotland supporter would agree that this is where, in a fair and equal world, the great prize truly belongs. International football was born in Glasgow and Scotland has produced more talented players per head of population than any other small country - think of Denis Law, Kenny Dalglish, Jim Baxter and Jimmy Johnstone - while Scottish supporters have shown in huge numbers how much they enjoy being at the World Cup finals. The deserved rewards for such a blend of talent and devotion are to be found in this tale of Scotland achieving World-Cup success, putting them on the same level as the great footballing nations - Brazil, Italy and Germany. This alternative version of Scotland's World-Cup history is truly the stuff of which dreams are made.

Release date: October 24, 2013

Publisher: Headline

Print pages: 318

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Dreamland

Graham McColl

Football Association’s tea-lady manoeuvres her way into his office, nudging open with her left shoulder its heavy oaken door

with practised ease at the same time as nimbly balancing a tray laden with teapot, cups, saucers, newly toasted muffins, various

chocolate biscuits and cakes. ‘It’s caused more of a song and dance than Gracie Fields ever did,’ Graham brays, ‘and it has

given a lot of people a lot of ideas above their station! And I wish whomever it was that discovered South America had never

bothered their backside! What did the Brazilians or the Argentinians or the Peruvians do in the war? Hee-haw! Now, while we’re

struggling to get together the basics of life again after saving the world from that madman Hitler, these FIFA people are interfering and trying to bring

to an end the game that we gave to the globe! It’s beyond hilarity, it really is . . .

‘They’re also saying that Hitler and his henchmen are actually hiding out in South America. Can you believe it? Maybe he’s

behind all this, this World Cup. As well as all that, there wouldn’t even be a FIFA if it weren’t for us. You’ll remember,

Janet, that match we held just after the war at Hampden Park – Great Britain against the Rest of the World – well that was

a fundraising stunt for FIFA and if it hadn’t been for that game they’d have gone broke, bankrupt, kaput. Then this is how

they reward us.’

Janet Haugh puts the tray down carefully on the edge of the SFA secretary’s desk. ‘Yes, Mr Graham,’ she says, respectfully,

turning over the two cups onto their saucers and pouring. ‘That’s fresh blackberry jam to go with the muffins, Mr Graham.

I managed to get an extra ration of sugar so I made it this morning. Shall I tell Mr Kirkwood to come through now?’

‘Yes, yes, Janet, yes, please do,’ Graham says, calmer now for his letting loose his feelings, ‘and that’s very nice about

the jam. Thank you.’

‘Oh, Mr Graham, the sweet salesman, Mr O’Flanagan, dropped by at lunchtime and popped in half a dozen Fry’s Cream bars for

you. He said they’re “on the house”.’

‘O’Flanagan, eh? Can’t say I care much for that fellow but if he’s dispensing favours such as that, we can’t turn him down,

now can we? How he’s getting his hands on Fry’s chocolate bars in these times I don’t know. I suppose he’ll be looking for

tickets for the match next week. Still, what are a couple of tickets when he’s dishing out such rare luxuries? I’ll collect them on my way out this evening. Thank you, Janet.’

Droplets of rain splatter against the first-floor window of the SFA’s offices at Carlton Place as Graham sits back in his

chair and contemplates the River Clyde, grey and churning along slowly beneath a spring sky that is its mirror image. The

man known in the press as a stormy petrel is in subdued mood this deadening April afternoon. He rises and, using a pair of

tongs beside the grate, places enough precious lumps of coal on the fire to see it through the remainder of the chilly day.

After more than two decades as SFA secretary and having presided over a stable, settled time for the sport, even through the

war hiatus, now he feels assaulted by the forces of modernity and, especially, by the twin threats from Brazil and Colombia

that have put him under pressure like never before.

It has all come to a head two days previously. A goal from Roy Bentley, the England forward, sent Scotland tumbling to a home

defeat in the annual match against the Auld Enemy. During normal times, the Scottish supporters would have been content to

swear revenge on the English at Wembley in a year’s time but these are abnormal times and much rage is, instead, being turned

towards the SFA. FIFA has generously decreed, in honour of Britain’s status in founding the game, that the top two in the

Home International Championship will be allowed entry to the World Cup finals, to be held in Brazil in summer 1950. England’s

win has seen them top the table; the Scots have finished second. Graham, though, has long stated firmly that he would only

take a Scottish squad to Brazil if they were champions of Britain. Even some English players have pleaded for leniency on

their opponents’ behalf – making direct appeals to individuals inside the SFA in the immediate aftermath of Saturday’s match – but Graham is uninterested and will not be swayed.

Additionally, trouble is brewing from the direction of Colombia, where the leading clubs are offering top British players

more money in a year than they could earn in a career at home. Scots are prominent among those in demand. British league football

remains preeminent in the world, with Scots widely regarded as its principal entertainers and conjurors of magic and they

are thus attractive to the Colombians as they seek an injection of foreign talent into their football. In his desk drawer,

Graham has a secret list of no fewer than 180 Scottish players who have asked Joe Dodds, a Scottish agent for the Colombians,

to arrange a deal for them.

‘Oh, there you are, Kirkwood,’ Graham calls out cheerily as the SFA treasurer enters the room. Robert Kirkwood, a tall, rangy

man, with a slim moustache, dark brown wavy hair and a cigarette constantly on the go, never fails to lift Graham’s spirits.

Kirkwood exercises his duties with a light touch that contrasts with that of the dogged, stolid SFA secretary and his very

presence in the room buoys Graham, not a smiling animal, lifting his confidence that he can see these tough times through.

‘There’s talk today in the town that HM Government may be about to go a bit easier on the old sugar rationing,’ Kirkwood says

as he takes a seat on the other side of Graham’s desk and draws a cut-glass ashtray towards him. ‘That should cheer folks

up a bit after that sorry spectacle against England on Saturday.’

‘Yes, yes; anything will do at this time,’ Graham responds as Kirkwood plucks a chocolate éclair from the tray, delicately

puts it to his lips and manages to consume it cleanly, without endangering the spotlessness of his neatly cut, blue, three-piece woollen suit. The treasurer gazes absent-mindedly out of the window at the unremarkable sky, before taking up

his cup of tea and languidly rekindling his conversation with Graham.

‘You know how I feel about it all, George, don’t you?’

‘Yes I do,’ Graham answers. ‘I am aware that you think it a good idea that we go to this World Cup but I agreed with the Irish

and the Welsh that we would only accept a World Cup place if we won the group and I cannot go back on my word now!’ Graham,

agitated, brings his fist down on the table, making his cup jump, displacing some of its contents and sending a couple of

Tunnocks caramel logs tumbling to the floor. ‘Sorry, Robert, it’s just that all this is getting to me. I feel as though we’re

being publicly blackmailed to go to this World Cup and I won’t stand for it.’

Kirkwood nods reassuringly then continues. ‘You know, George, old chap, it’s all very well for the Irish and Welsh to agree

to such a thing but you know, and I know, and they know just how slim their chances were of finishing first or second. We

beat the Irish 8–2 over in Belfast, remember, and the Welsh didn’t offer much resistance when we beat them here at Hampden.

It suited them to hold us to that agreement – no skin off their noses and it helps their feeling of security. England never

were party to such an agreement, were they? And you can be jolly well sure that if they had finished second to us they would

still be winging it on that aeroplane down to jolly old Rio next month. I say, chocks away and we join them. I must also say

that there is as much at stake for those of us inside this building as for anyone else.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Well,’ Kirkwood continues, after drawing slowly on his cigarette and carefully tipping the ash, ‘I spoke to Stanley Rous when our English chums came to the boardroom after Saturday’s game and the word is that my place on the FIFA international

board is in severe jeopardy if we don’t go to Brazil. Stanley also told me, on the q-t, that, as secretary of the Football

Association, he feels he is next best thing to a shoo-in to be the next FIFA president when Ivo Schricker retires after the

World Cup, and that Arthur Drewry, the England selector, could be getting the chairman’s job. So our English friends, in turn,

will be handing out favours, including some jolly good jobs, in the next year or two – and that’s where you come in, if you

get my drift . . .

‘Bear in mind, old bean, that this whole FIFA thing is going to explode over the next few years with the World Cup and what

not – Stanley is sure of it. It’s going to be quite a beano and the top bananas are going to have a jolly good ride on the

back of it all.

‘Besides all that, I honestly feel that this World Cup thingy is a pretty splendid idea. Flavio Costa, the Brazil manager,

was another of our guests on Saturday and he assured me that the whole thing is going to go with a bang: he says the stadium

they’re building in Rio to hold it this year is going to be the biggest in the world – huge enough to hold 200,000. Doesn’t

that speak for itself? He entreated me to do everything in my power to try to get you to change your mind because the Brazilians

would love to have us over there. Do you know that he’d come all the way over from South America and he’d stayed at the Marine

Hotel down in Troon for several days just to plead with you? You refused even to meet him. I must say I was very disappointed

in that, old boy.

‘Anyway, what’s the time? Quarter past four already. Time I wasn’t here. I’ll leave you to chew it over . . .

‘And remember, you’d be a hero to the chap in the street if you were to come around. I was in the Horse Shoe bar – dropped in for a glass of porter after lunch at the Central Hotel

– and the fellows in the booth next to me were working themselves into a frightful froth over the team not going to the World

Cup tourney. I won’t repeat every word they said – I shall spare you that – but, in a nutshell, they weren’t too impressed

by your sticking to your position. So you can only do yourself and everyone else a lot of good by performing an about-turn.

‘Well, I’ve got an appointment with the chairman of St Johnstone for a spot of golf up at Gleneagles tomorrow so, see you

Weds old boy – toodle-pip!’

As Kirkwood glides out of Graham’s office he takes a quick, assessing glance over his shoulder at the SFA secretary, sitting

deep in thought, his rotund trunk and chubby face, plus thick, round spectacles, making him look more than ever like the Michelin

Man, observes Kirkwood; that, or an outsized baby. ‘Hope that’s done the trick,’ Kirkwood mumbles underneath his breath, flashing

a ready smile at Janet Haugh as he collects hat, coat and brolly from the stand in the lobby and prepares to meet head-first

the bracing elements.

Graham, meanwhile, levers himself up from behind his desk and, hands behind back, face tight with irritation, begins pacing

up and down the length of his office. While Kirkwood’s presence always cheers him, there is, also, almost always some dissatisfaction,

a feeling of inadequacy, on Graham’s part when the man leaves. This time is no different. Graham had sought reassurance from

his colleague but has instead been left with a whole lot of loose ends and nagging doubts, which is just what he did not want.

‘That’s just what I did not want,’ he bellows to the empty room, ‘that’s just what I did not want!’

A brown leather, lace-up football, a gift from Tomlinson’s, the sports equipment distributors, is lying in the corner of the room and in his fury and frustration, Graham rolls it out

and gives it a powerful dunt with his right foot. He intends a rebound off the office wall but loses balance slightly as he

strikes the ball and it flies off his smartly polished brogue at a sharp angle and goes straight through the window. Janet

Haugh comes running in, as do two junior administrators, to find a puce-faced Graham being cooled by the chilly blast of fresh

air now entering his lair through the newly cracked window.

‘Blasted kids!’ Graham yells, affecting to look down into the street for the alleged miscreants. ‘What do they think they’re

doing, playing football in the street? Look, that’s their ball there, must have run away without it. Some of those scallywags

from the Gorbals, no doubt. There ought to be a law against it; shouldn’t be allowed . . . why they want to kick a ball around

in the street I don’t know.

‘Eh, Hogg, could you ask the glazier to come out right away and get that window fixed?’

· 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 ·

If there is one element in George Graham’s character in which he takes pride more than any other, it is his sheer, stubborn,

cussed, obstinate determination not to be shifted in his thoughts by the changing fashions of the day. Six weeks after that

meeting with Kirkwood – as Scotland conclude a brief tour of continental Europe – he remains adamant that they are not going

to the World Cup, which will kick off in late June; only a month away. The Scots win against France in the tour’s final game and, later, during the post-match banquet at the Hotel Pavillon Henri IV in Saint Germain-en-Laye, Graham

rises slowly to his feet, ready to deliver his speech to the hosts.

‘Middens and Mon-sewers,’ he says, turning with a nod and a smile to the French Football Association officials, ‘I must thank

you very much for your hostile . . . hospital . . . horse . . . pallity . . . Oh, you know what I mean . . . And I must also

thank Mr Rémy Martin; is he in the building? No? Well, if you do see him, say that his little tipple went down a treat. Well,

with me, anyway . . .

‘Now, poor linguist as I am, I can still tell that all the talk here tonight is of only one subject: the World Cup. And, on

that very subject, may I congratulate our French hosts in sharing with us and Portugal, our previous hosts on this tour, a

very, very special hat trick – that of refusing to compete in this silly, new-fangled World Cup championship in South America.

‘When we played England last month with the so-called “prize” of a berth at the World Cup riding on the match, it had the

effect of relegating our annual encounter to the level of a cup tie and a foreign touch was conferred on that match that we

would rather do without – if our hosts here don’t mind me saying so.

‘With all due respect to those present tonight, in the past few years we have seen players lusting after money in an open

and a despicable way. This World Cup will, I’m sure, only make things worse. Look at what the Colombians are doing right now

– they’re stealing our very best players from under our noses. Two hundred Scottish players have registered interest in switching

to the Colombian League, tempted by signing fees of anywhere between £3,000 and £10,000 plus weekly wages rumoured to be anywhere

between £120 and £500 – and a swish, new home and a high-powered American car thrown in to boot. Prostitution it is! How can we protect our

game, our Corinthian spirit, in the face of this blatant appeal to naked greed?

‘Flavell of Hearts has gone to Colombia, spirited away like Cinderella at dead of night, coat over his head and on to an aeroplane:

Jimmy Mason, Alec Forbes, Johnny Kelly, Jimmy Walker, Jimmy Docherty, the list of Scottish players who have been approached

is just about endless . . . All of them were tempted away by one Joe Dodds – a former Scotland internationalist no less, but

with a stronger siren voice than Anne Shelton and a man being paid, I am reliably informed, two hundred pounds for every player

he can cart out of Scotland and into Colombia.

‘Now, the upshot of it all is that the players’ union in England – Colombia is poaching south of the border, too – is agitating

for five-year contracts, with wages guaranteed at the same level throughout and at the end of which players would become free

agents.

‘Ridiculous! It’s like a comic opera dreamed up by Bud Abbott and Lou Costello but it may mean the wrecking of our best club

teams and our international sides too!

‘Damned Tartars that they are!

‘So all of this is what happens when faraway countries start to influence our game and I am sure this World Cup in Brazil

will be the same. So it is a damn fine thing we are not going to it. No one abroad, it would seem, believes us when we say

our sole reason for turning our back on the World Cup competition is principle . . . The general perception is that we are

scared to go in case we find ourselves outmatched. Nothing could be further from the truth. These two tour matches – against

Portugal and France – were arranged specifically as warm-up encounters for the World Cup in the event that we had been going but we finished second in

the Home Internationals so we don’t go to Brazil. That’s the long and short of it and, I must say, it’s the first time I can

see a lot of good having come from us finishing second to England. We don’t go to the World Cup. No! No! No!’

As Graham settles unsteadily back into his seat, his face flushed bright red, with an astonished silence emitting from the

assembled company, George Young, the Scotland captain, rises to give his own speech of thanks. Discarding his prepared notes,

he pauses, and takes a long look at the SFA secretary. ‘Mesdames and messieurs,’ he begins, ‘I have to thank you all for proving

such genial hosts, for laying on such a fine banquet and for providing such demanding opposition in today’s match; one from

which we were relieved and pleased to emerge as victors.

‘With the World Cup such a burning topic at this moment, I feel that I must make mention of it. As the representative of our

Association, Mr Graham’s words must be respected with regard to their objectivity – it is, of course, probably neither here

nor there that we players are united in wanting to partiipate in the World Cup. We probably don’t know what is best for us.

‘Without further ado, and in recognition of our enjoyment of this short tour, I would now like to make some presentations.

To our kindly French hosts, I would ask that they do us the honour of accepting this case of finest Scotch whisky with which

to remember us with fond and soothing thoughts. For Alex Dowdells, our wonderful trainer, whose humour and good nature have

sustained us here on the continent, a set of French boules – I know he is an enthusiast – and a bottle of champagne, which I hope will go down well, too. For George Graham, our esteemed secretary, a suitcase. I know that while we

players are not likely to be in Brazil this summer, Mr Graham has willingly accepted an invitation from FIFA to represent

Scotland in an official capacity, and so I hope that Mr Graham will take this suitcase to Rio with him and that, every time

he opens or closes it, he will think of my fellow team-mates and I who so wished to be with him but were denied that pretty

opportunity.’

Spontaneous applause erupts throughout the room and Graham, suddenly wrenched into a moment of sharp sobriety, fixes Young

with a cold, hard stare.

· 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 ·

‘Champagne!’ Robert Kirkwood shouts, half-turning his head toward a waiter as he settles into an elegant chair in the lounge

of the Henri IV. Opposite him, George Graham, bleary-eyed, visibly brightens at the thought of a sparkling nightcap to revive

his spirits following what he regards as Young’s insubordination.

‘I thought George Young made some good points,’ Kirkwood says, folding a note into the appreciative waiter’s hand as the bubbly

arrives, ‘and having mulled it over, and having witnessed the enthusiasm of the players to participate in the World Cup, I

must inform you that we will, after all, be going to Brazil. I’ve spoken to Young about it and he tells me that the players

will happily change holiday plans, etcetera, in order to play in South America.’

‘The Scottish team will go to this World Cup over my dead body!’ exhorts Graham, causing a few heads to turn in surprise at his outburst.

Kirkwood gives a fresh cigar a couple of puffs to get it going, closes his lighter and replies, calmly, ‘You know, old bean,

you could not be more right. We will be going to the World Cup and if you continue to disagree with that, then you will be

pretty much dead. I don’t mean literally, of course, dear me, no, but figuratively you will be a dead duck. You see, I know

all about the tickets.’

‘What do you mean?’ Graham interjects.

‘What I mean is,’ Kirkwood continues, maintaining his even tone, ‘that I have been aware for some time of the discrepancy

between the number of match tickets you release for sale to the general public and the number printed. I put two and two together,

carried out investigations inside Carlton Place, and discovered that more than 6,000 out of the 134,000 tickets for the England

match last month – tickets that were printed – were not passed on, by you, for general sale.

‘I don’t know what you did with them but I can guess . . . That’s an awful lot of money for the Association to lose and for

someone to use for the purpose of lining their own pockets. I’ve gone back over a few years and I see the same pattern for

big matches – internationals, cup finals. Obviously, it has got to stop – and I’ll say no more about it. Unless, that is,

you refuse to see sense and reverse your decision not to attend the World Cup, where we can claw back some lost revenue. If

you refuse, I shall send a telegram first thing tomorrow morning to Malcolm McCulloch, the chief constable, asking him to

send some of his men to meet us at Abbotsinch airport when we step off the plane from France. I’m sure you’d be only too pleased

to help them with any questions they may wish to ask you.’

· 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 ·

The Dakota carrying the Scotland party circles above the great city of Rio de Janeiro, with Sugar Loaf Mountain jutting out

above it majestically and Copacabana beach stretching seemingly into infinity. ‘It’s like fairyland in Technicolor,’ shouts

Scottish forward Billy Steel, to general amusement.

The Scotland players from the European tour remain in a general state of disbelief that they are here at all, as does Jimmy

Mason, whose addition to the party was demanded by his team-mates because, as Hibernian striker Lawrie Reilly suggests, he

is the type of player who makes it impossible for those around him to play badly. No one is in a greater state of shock than

George Graham, even though it was he who, at the Henri IV on the morning after the banquet, had announced that Scotland would,

after all, for the general benefit of the game and in response to the heartfelt pleas from associates abroad and, especially,

at home, attend the finals of the World Cup.

Graham remains resentful at having been outmanoeuvred by Kirkwood but, as he cranes his neck to look down upon the carnival

city and Copacabana beach, the players’ excitement feeds through to him and he wonders whether there might not be something

in this World Cup thing after all.

· 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 ·

‘Unparalleled scenes greeted the England and Scotland squads when they stepped off their shared transatlantic flight to Rio

de Janeiro today,’ W. Capel Kirby, one of the few British pressmen to attend the World Cup, reports, in a story sent back to Britain on 20 June 1950.

I arrived here on the same plane as our favourites and we found that this famous Brazilian city has gone quite haywire with

football excitement. At the airport, pandemonium broke loose as we stepped from our plane and it seemed as if the English

and Scottish boys’ appearance was the signal to relieve the pent-up excitement of weeks of anticipation. There was every evidence

that the sight of Billy Wright and his mates and George Young and the Scottish players had brought things to a climax but

curiously enough, the fans of Rio are not thinking of England – or the Scots – winning the Cup. Brazil are favourites, with

Uruguay mentioned as their closest rivals. The most favoured country from Europe is Spain. These Latins either know something

we don’t or they plain like to keep things local.

· 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 · 1950 ·

Rio this June of 1950 is making Glasgow look as football-crazy as a Home Counties suburb. Every foreigner is accosted by groups

of locals demanding to know where they come from and what they think of Brazil’s chances of winning the tournament. Even the

more wide-eyed among the visitors quickly realize that the best option is to smile and say ‘Bra-zeeel!’

Down at the Copacabana Palace Hotel on Rio’s seafront a rare sight is unfolding. George Graham is enjoying a break between

the official pre-tournament referees’ reception and a gathering of FIFA’s international committee. Not only has the SFA secretary, self-appointed bastion of propriety back home, divested himself of customary homburg, waistcoat and tie but

he is, feet splayed, arms outstretched, attempting to mimic local dance moves in the wake of two young Brazilian ladies, tournament

hostesses. This performance is taking place in the hotel ballroom, which is crowded with FIFA dignitaries, local football

officials, journalists, translators, facilitators and administrators, all of whom are being attended to solicitously by an

army of waiters offering an impressive array of refreshments.

‘I’ve never had such a hectic day,’ Graham – taking a break from the dance floor – confides to Swedish delegate, Lars Agelmo.

‘I think I’ve met a representative of almost every nationality in the world and, to make sense of every conversation . . .

Well—’ Graham pauses to mop his dripping brow, ‘I would have needed at least a dozen interpreters following my every step.’

‘You seemed to be following well the steps of those delightful girls,’ offers Agelmo with a grin. Graham, lost for words,

merely gives a shake of the head and exhales heavily. ‘I’v. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...