- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

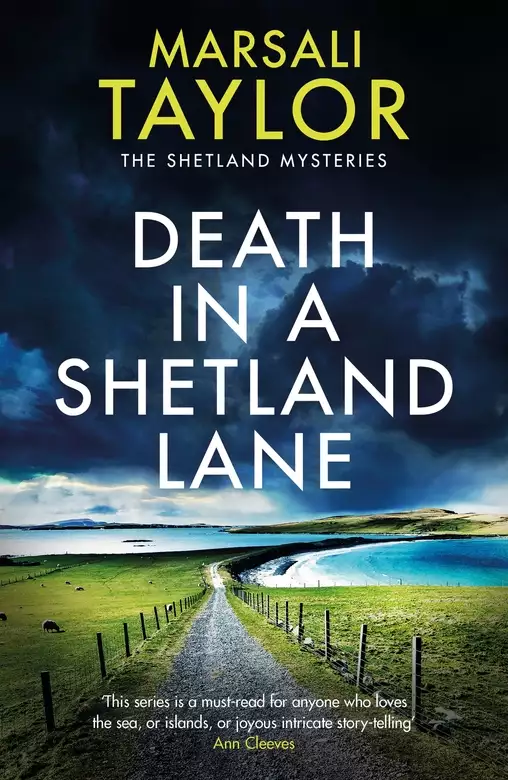

'This series is a must-read for anyone who loves the sea, or islands, or joyous, intricate story-telling.' ANN CLEEVES

Days before the final Shetland fire festival, in broad daylight, a glamorous young singer tumbles down a flight of steps. Though it seems a tragic accident, sailing sleuth Cass Lynch, a witness at the scene, thought it looked like Chloe sleepwalked to her death.

But young women don't slumber while laughing and strolling with friends. Could it be that someone's cast a spell from the Book of the Black Arts, recently stolen from a Yell graveyard?

A web of tensions between the victim and those who knew her confirm that something more deadly than black magic is at work. But proving what, or who, could be lethal - and until the mystery is solved, innocent people will remain in terrible danger...

Release date: April 13, 2023

Publisher: Headline

Print pages: 352

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Death in a Shetland Lane

Marsali Taylor

(The stone that doesn’t lie in your path doesn’t break your toes.)

Avoid getting into matters which are not your concern.

It was the night of the black moon. Yesterday there had been just the thinnest sliver of silver outlining one side of the dark circle, and tonight there was nothing, just blackness, so that Lizzie Doull stumbled into the chair in her attic room as she made her way to her bed. She’d taken off her frilled apron and barely started to unbutton her blouse when she heard the gate latch click. Outside there was a circle of light, a lantern moving up the path towards the front door.

It was her work to answer the door. She flung her apron back over her skirts, tied it at her back waist and began to hurry down the stairs, fumbling her blouse closed again as she went. The knocker sounded as she was halfway down, a tentative knock, as if the caller had seen the house was in darkness, then a second one, a loud rapping as if the business, whatever it was, wouldn’t wait until morning. She reached the ground floor, smoothed her long skirts and went forward to undo the chain and bolts, and open the heavy door.

It was Joanie Williamson from the Haa o’ Midbrake standing there. She’d kent him all her life. He was her father’s age, and she remembered him from when she was a peerie thing. He’d had a croft, but the speed o’ him was like the sun upon the wall. His tatties were planted later than anyone else’s, his sheep sheared last, his peats left on the hill to bring home as he needed them, so that he was taking the last of them off as the rest of the village was sharpening their tuskers for the spring casting. He went into Lerwick more often than they did, and sat in the pub yarning, and her father shook his head over him, and said he’d never come to any good. Well, Faither had been wrong, for two years ago last hairst he’d seemed to take a notion to himself, and smartened himself up. He’d courted a wife from Nesting, and all of a sudden he was like the man in the story, everything he touched turned to gold. A man from south took a fancy to his sheep and bought the lot at a ridiculous price, and with the money Joanie’d taken over the shop. His wife served at the counter, and he delivered the messages to the gentry, local goods along with fancy goods which nobody but gentry could afford to buy. Now he had two girls in service with him, one in the house and one in the shop, and a nursery-maid for the baby, and they all came along to the kirk on Sunday and sat in a pew to themselves just behind the minister’s household.

Lizzie’d been watching his face in the kirk. At first he’d come in and plonked himself down with a defiant air, as if he kent fine he was pushing forward to make a silk purse of himself when he was nothing but a sow’s ear; then gradually she’d seen new lines on his brow and a haunted look in his eyes. When he came in with his grand wife and two servant lasses coming before him, he’d give an uneasy look behind him before he pulled the door to, and as he left he’d look all around and pull his coat close to him for a moment, before he remembered who he was now, and straightened up again, ready to shake the minister’s hand and greet him with a voice that was just too cheery.

Now his face was white as a sheet and his voice trembled as he asked if the minister would see him. He was sorry it was so late at night, he said, but his business was urgent. He made a half-gesture towards the bulky parcel under his arm, then stopped, and clutched it to him.

‘Aye, sir,’ Lizzie said, as she’d been taught. The parcel was rectangular, the size of one of the tin deed-boxes she’d seen Mr Duncan the lawyer bring to the minister from time to time, and wrapped up in a blanket. She heard the minister’s step on the stair behind her, and turned to him. ‘Mr Williamson on urgent business, sir.’

‘It must be urgent indeed to bring you out at this hour,’ Mr Macraisey said. ‘Give Lizzie your coat and come into my study, Mr Williamson.’

Lizzie reached for the parcel, to lay it on the table while he took his coat off, but he snatched it away from her hands with a growl of alarm, and held it firmly while she pulled first one sleeve then the other down and took his coat to hang.

‘Mr Williamson’s hat too, Lizzie,’ Mr Macraisey said, ‘and bring us a tray with two glasses.’

When she came in with the tray, they were sitting with serious faces, and the parcel was on the table, the blanket lying beside it. It was indeed a deed box, and it had been open, but as she pushed the door Mr Macraisey had leaned forward to close it, so that she didn’t see what was inside. ‘Leave the tray here,’ Mr Macraisey said, ‘and go back to bed. I’ll show Mr Williamson out.’

He’d never said such a thing before, for he was one to stand on his dignity, the minister, but Lizzie wasn’t going to complain about not having to wait up, except that she was curious. She couldn’t wait by the door to listen, for the minister would be expecting to hear her steps go up the stairs, but she undressed slowly, listening for the front door, and when she went to bed she lay awake for a while. It seemed a long time later that there were steps in the hall, then the creak of the door and the glint of the lantern on her ceiling. She rose at that, keeping her face well back from the window so that nobody would see her spying. Both men were coming out of the house, Joanie Williamson still with his parcel under his arm, and something long that she couldn’t make out in his other hand, Mr Macraisey carrying the lantern. She watched as they went to the gate, across the track and into the kirkyard. The lantern shone on Joanie for a moment as he passed through the kirkyard gate, and she saw the long thing was a spade. They went to a corner of the graveyard where nobody was buried. Joanie and Mr Macraisey stood facing each other for a moment, formal-way, and then Mr Macraisey held a silver sixpence up in the light of the lantern, and Joanie took it, and gave him the parcel. She heard the crunch of a spade, and saw the blade flash in the pale circle of lantern light. Joanie was digging. She waited, and waited. At last the noises stopped. There was a long pause. She saw Mr Macraisey bend down and place the parcel in the hole, then hold the lantern while Mr Williamson covered it up, shovelling the earth as if he was afraid the box would come backup out of its grave by itself if he didn’t get it covered quick enough. When all the earth was in, he stamped hard on the ground, then replaced the turf and pulled a piece of broken gravestone over to lay on top of it.

She saw their faces as Joanie lit Mr Macraisey back to the door. Joanie’s was filled with relief; Mr Macraisey was grave and uneasy. He came into the house and Joanie bobbed away across the dark moor, his circle of light diminishing until he went over the rise and the darkness flowed in once more.

The next morning Mr Macraisey reminded her that she wasn’t to mention people who came to the Manse; she was to forget she’d seen them. ‘Are you remembering that, Lizzie?’

‘Yes, sir,’ she said, and curtsied. But she didn’t forget Joanie Williamson’s visit.

Her nan couldn’t be left alone for long now. Lizbet didn’t mind sitting with her, the last of these dark evenings before spring brought the bonny light nights. If Nan was sleeping, well, she could watch the music channel on the telly and dream of someday making videos like that: walking slim and athletic along Breckon beach at sunset, singing her heart out to the waves, or meeting a handsome lover in soft focus, or the ‘in concert’ ones with the cheering crowds, the lights dazzling the stage, and her in the middle of it, holding them spellbound. Sometimes, when Nan’s head was clear, she’d chat away, just as she used to, asking Lizbet how her Saturday job in the shop was going, and what kitchen gadgets folk were spending money on nowadays: ‘My mercy, did you ever hear the like? They must have more money as sense.’ When her head was clouded, she’d tell stories, mostly ones Lizbet had heard over and over, tales of her time in service at Busta House as a girl between the wars, or of working at the camps when oil came to Shetland. Her husband, Lizbet’s great-grandfather, had been killed in the Second World War, in the east, and Nan had met an American in the camps, and nearly gone off with him to Texas. ‘Imagine that! You could all have come and visited me on a ranch, just like in the Westerns.’ Sometimes she reached further back into her memory and told some of her own grandmother’s tales, the tale of the Trow o’ Hakkrigarth, and the night she saw a ghost walking home from a wedding dance, and the one she was starting on now, the story of how when her grandmother had been in service at the old manse, she’d seen the minister bury something in the kirkyard one night at dark of moon; the tale her own grandmother had told her when she was dying. ‘I’d never heard it from her before,’ Nan said. ‘She said someone ought to ken what was buried there.’ Nan’s faded blue eyes looked uncertainly around the room. ‘I think I should maybe tell someen now. It mustn’t be dug up again, never. But then, you’re a young lass, and it maybe shouldna be you I tell.’

Lizbet was intrigued. ‘Mam’s no’ home, so if you need to tell someone it’ll have to be me. So what was in the box? I thought she didn’t see inside it.’

‘That she didna. It was later that she put twartree rumours together and worked out what she’d seen. The way Joanie had prospered, after being the most pushionless creature, and the minister giving Joanie the silver sixpence, and taking the box, and burying it.’ Her Nan paused for a moment, struggling for breath. ‘The thing that the minister bought and buried in that kirkyard was the Book o’ the Black Arts.’

Tuesday 14th March

Tide times, Brae:

LW 00.32 (0.98m);

HW 06.30 (1.66m);

LW 13.03 (0.75m);

HW 19.15 (1.66m)

Moonset 06.30; sunrise 07.23; moonrise 12.18; sunset 19.04. Moon waxing gibbous.

Der had a craa’s court apon him.

(They’ve held a crow’s court on him.)

He has been judged and sentenced by a clique with no defence allowed.

The girl in the dark coat was huddled up at the far end of the beach, head bent, knees up against her chest, back pressed against the last corner of the low bank running around the beach edge, as if she had run as far as she could and pressed herself against the earth in the hope it would hide her. I glanced up at the road above the beach. There was a car there, parked where the track ended in moorland, wheels only just on the gravel, bonnet sticking out over the heather.

I ran the motorboat onto the beach halfway along, pulled her up enough to hold her and scrunched towards the dark hunched shape at a steady pace, not quite making as much noise as I could, but scuffing enough so that she would hear me coming. The brown head turned further seawards, the body made a little turn so that her back was square on to me. The feeling I should respect her privacy struggled with knowing something was badly wrong here. She was young, I could see that, a lass in her late teens or early twenties, and I was an adult who spent her days in charge of teenage trainees on board a tall ship. I couldn’t walk by. I took a deep breath and went almost up to her, stopping ten metres short and sitting down on a handy rock. ‘Fine day for a walk,’ I said.

She hunched one shoulder towards me. ‘Aaright,’ she agreed. Now leave me alone was unspoken. I stayed put and waited. ‘No’ as cold as it might ha’ been in March,’ she added. She had a singer’s voice and a Yell accent; that aa sound was unmistakeable. Only Yell folk could pronounce the Norwegian town Å properly.

I’d heard that voice before. I tried to place it and visualised coloured lights, the boating club, this same voice joking, ‘No’ as cold as it might ha’ been in June.’ Outside. Some sort of doo, Regatta day maybe, and they’d set up a stage in front of the club, beside the barbeque queue. Local bairns with fiddles and accordians, and several fledgling groups, and this girl had been the singer in a group . . . No’ as cold as it might ha’ been in June, and then she’d launched straight into one of those fifties show songs. ‘June is Busting Out All Over’, the sort of title to bring out the worst jokes from sailors who’d had a dram. She had a beauty of a voice, rich and full, lower than you’d expect from a young lass – and with that I got her pedigree. She was one of my friend Magnie’s Yell cousins.

I said that first, by way of reassurance. ‘You’re Magnie’s cousin, are you no’?’ My memory was fighting for her name. Elizabeth, no, Liz. Lizzie . . . Lisbeth. I said it. ‘Lisbeth.’ It didn’t sound quite right. ‘No, Lizbet, isn’t it? You’re the one with the amazing voice.’

I’d meant to be complimentary, but I’d hit the wrong nerve. She gave a wail and buried her head in her knees. Her shoulders shook with sobs. She poured out an incoherent sentence which ended with an impassioned no good and lifted a tearstained face to glare at the waves.

I gave the boat a quick glance, noted that the cats had jumped out and were investigating the tideline, yellow and pink lifejackets bright against the brown seaweed, and shifted to a closer rock. ‘If someone’s saying your voice is no good,’ I said firmly, ‘they’re talking nonsense. Your voice is very good. I heard you only once, it must have been two regattas ago, nearly two years, and I remembered you.’

She shook her head and sniffed, then drew her hand across her eyes and stared bleakly across the tumbled waves of the Røna to the hills of Vementry behind. Then she turned her head to look at me, half-shy, half-shamefaced. ‘It’s no’ my voice. It’s me that’s no’ good enough. I’m no’ pretty enough.’ Her voice cracked. ‘It doesna matter how good I am, how much work I put in, if I’m no’ sexy as well.’ She put her head back on her knees for a moment, then lifted it again, resolutely blinking the tears away. ‘You’re Cass, aren’t you? You’re that brown I took you for a tourist.’

‘My ship’s been in Africa,’ I said. It had been stickily, blazingly hot, and in spite of all the high-factor suntan lotion I’d slathered on, the scar on my right cheek ran white across my tan.

Lizbet wasn’t worrying about my scar, though that was probably what had reminded her who I was. ‘You ran away to sea, because that was all you wanted to do. You were sixteen, and got on a tall ship in France and never came back to Shetland till two years ago.’

I shouldn’t have been surprised that she knew all about me. Magnie knew everything about everyone.

‘But suppose,’ Lizbet said, ‘suppose the ship wouldn’t take you? Suppose you’d turned up and they said You’re too small or We don’t want girls. What would you have done then?’

‘She was a sail training ship, and I’d booked my passage, so I knew she’d take me.’ I stuck my chin out. ‘But I’d have found another ship. I worked, I did waitressing and dish-washing, just to get to sea, because it was what I wanted.’ I looked at her flushed face. ‘Not just wanted. Needed. I needed it more than anything in the world, more than exam results or boyfriends.’ I let that thought linger for a moment, then said, ‘But don’t tell me you’re not getting gigs locally.’

She nodded, and shuffled round towards me, uncurling her legs a little.

‘Have a rock,’ I suggested. ‘It’s less damp on the bum.’

She nodded again, and came stiffly upwards, then sat down, facing me, and with her back to the chilling wind. ‘It’s never been a problem here in Shetland. We’ve done loads of gigs, me, Tom, he’s the guitarist, and Chloe.’ Her voice snagged, like a kinked rope hitting a block, then continued. ‘She’s my pal, she does backing vocals. We do pubs, and clubs, and this year we’ve been asked to do a set at the Folk Festival. Only, today, well,’ she gestured back towards Brae. ‘You’re the Stars! You ken, the TV talent show. The auditions, in the Hall here, and in Lerwick tomorrow.’

Ah. Her ambitions and dreams and talent had hit the commercial world head on. When there were dozens of good singers about, the ones who got further all happened to be slim, tall and pretty.

‘We applied,’ Lizbet said. ‘Ages ago, as soon as we heard about it, and they gave us a slot. It wasn’t televised or anything, like, just the heats to possibly be in the regional heats next month. I was so nervous, because to get that kind of exposure, it’s everyone’s dream. I thought it went well.’ She paused, then repeated, firmly, ‘It did go well. We sang a couple of crowd-pleasers, you know, ‘Love is Like a Butterfly’ and ‘My Heart Will Go On’, with me doing the leads and Chloe harmonising, and they seemed to like us. Then the presenters asked us to swap round, Chloe singing lead, just for one song.’ Her mouth twitched. ‘Well, it was okay, but . . .’

I nodded. ‘I ken. There’s more to singing than knowing the tune.’

She was silent for a moment. Her eyes looked as if she’d suddenly grown up. ‘So they paid us a few compliments, and thanked us, and we listened to the rest of the acts. I thought we had a chance. We’d done as well as anyone else and better than some, I knew we had. At the end we all filed out, and then once we got into the car park I realised I’d dropped one of my gloves somewhere, so I went back in to look for it.’ She stopped, swallowed. ‘I heard them. Backstage.’ Her cheeks crimsoned. ‘They, the presenters, they were talking about us. About me. The other one has a better voice though, one of them said, and the tall woman said right back, Plain as a pudding and two stone overweight once the cameras get on her. The blonde’s sexy, and she can be taught to sing.’

Her hands were trembling. She slid them between her knees and fought the tears back. ‘They didn’t know I was there. I left the glove and got out into the car park. Chloe was high as a kite and talking about going out to celebrate, and I couldna, I just couldna, so I said something about going to see Magnie, and I just drove away from there as fast as I could and kept going to the end of the road. I didn’t want to see anyone or try to talk to them. I just wanted to go somewhere I could howl like an animal, let it all out before I had to go back and face them. Chloe and I share a flat here in Brae, you see, and Tom still lives with his folk, but he’s always in and out, and they’d both be wanting to talk over every note and every little thing the producers said to us, and I just . . . I just couldn’t bear it.’ She sat in silence for a moment, then said bleakly, ‘So that’s Chloe in. She’ll get the invitation for the regional heats, and even if she says she’s my pal and doesn’t want to do it without me, I’ll have to tell her to take it. I’ll stay here being plain as a pudding and singing in pubs.’

There was nothing I could say to comfort her. She wasn’t as plain as a pudding, nor horribly overweight, not even in the clingy velour dress she wore under her black coat, but she wasn’t pretty either. She had wispy brown hair, with a fringe over her low forehead, sparse lashes over her brown eyes, plump cheeks, full red lips over a pudgy chin; the sort of face you might see every day behind a shop counter and fail to recognise on the bus home. She was pleasant girl-next-door, just like her fifties musical songs. She was the plain sidekick who got the comedy boy in the end, and went off with him to make apple pies for the church fete. The special thing about her was her voice, and it hadn’t been special enough.

Lizbet sighed, and rose. ‘I’d better go back and face them.’ She braced her shoulders and squared her chin. ‘Thanks.’

‘I wish I could help,’ I said. ‘I wish there was a magic wand I could wave to make the next few days better for you. But it’s like being at sea in a serious storm. There are times even I wish I was, well, maybe not onshore, but somewhere else. But there’s no magic wand. You just have to tough it out and believe it’ll get better.’

Something changed in her face the second time I said ‘magic wand’. She closed in on herself, her eyes moving quickly across the beach, the water, as if her thoughts were racing. Her carefully painted lips tightened, then she turned back to me. Her smile was mechanical. ‘Thanks, Cass. See you around.’

She strode up the beach to her car, did a several-points turn and drove away.

Dem at has muckle wid aye laek mair.

(Them that have much would always like more.)

Riches breed love of more riches.

It was a day atween weathers, as the old folk would say, a bonny, bright mid-March day with one gale just past and no doubt another few expected before March wore out. After the greys and blues of sea and sky as we’d crossed from Boston, the brightness and bustle of West African markets, the striplights of airports, it was good to be in the clear colours of home: a path of blue sea between low green hills, a great expanse of sky. It had been half-dark as we’d landed last night, but as the plane had come low in to the runway I’d glimpsed the sea pounding on rocks, and an old crofthouse with a sweep of hill behind it. My heart had lifted at the familiar sight. Home.

I’d seen gardens yellow with daffodils on the mainland, but Shetland was still poised on the transition from winter to spring. The sun danced on the water in the morning light, turning these northern seas back to spring blue, but the hills still wore their winter fur of weathered long grass, and there was no sign yet of the dark green heather shoots thrusting their way through last year’s brittle stems. The ghost of a half-moon hung in the sky.

I was on my way to check on my yacht, Khalida, sitting ashore at Brae. I called the cats from their investigation of the tideline, and put my shoulder to Herald Deuk, Gavin’s sixteen-foot motorboat, to shove her back into the water. My handsome grey Cat stayed up in the cockpit while I got the motor going, but tortoiseshell Kitten headed below to sit in her box and wash the sand from her white paws. I glanced down at her, lifevest glowing pink against her ginger-allspice-cinnamon fur. Her little face was pleased as she looked from Cat to me, then up at the moving sky. Cat sat upright in his corner, enjoying being at sea. He’d grown up as a ship’s cat, and I missed him on board Sørlandet, but my full-time live-aboard life had changed when our beautiful three-master had become an A+ Academy. Now we had sixty teenagers aboard for the school year, along with a set of teachers for academic lessons between watches. The ship’s crew worked eight weeks on, then flew home for eight off, which made it too awkward to take Cat back and forward; and besides, he’d miss his girlfriend, the Kitten, more than he missed me. Even as I thought that, he jumped down from the cockpit seat and went below to join her in the box. He bent his head to give her a lick on the forehead, and she sat up to sniff his whiskers and return the lick.

The eight weeks on, eight off, routine made things easier for Gavin and me too. DI Gavin Macrae, of Police Scotland. We’d met nearly two years ago, when I’d been his chief suspect in the Longship case, and, well, we’d liked each other then. I smiled, remembering the cautious way we’d moved around each other until spring last year, when we’d become lovers. We’d moved in together in October, when Gavin had accepted an Inspector post in Shetland on condition that life here included me. We’d had the last of my leave then, and another fortnight together over Christmas. This would be my first full leave at our cottage, and the longest I’d lived ashore since I was sixteen. I hoped it would all be okay, and that Gavin wouldn’t be so established in his own routines that I felt like an intruder – my fellow sailors had warned me about that one. I planned to spend his working days getting my own boat ready for mast-up, in April, as well as doing the partner stuff: cleaning, cooking, evenings together. I took a deep breath, gave one last look at the open road to the Atlantic shining behind me, and set my face landwards.

Gavin’s flash electric outboard took less than ten minutes to get us level with the bridge over to Muckle Roe. Five minutes more and I was bobbing gently in the marina. I’d meant to tie up at the dinghy pontoon sticking out into the circle of marina shorewards of the lines of larger boats, but this side of it was taken by a sizeable fishing boat bristling with those orange spools for unwinding baited longlines.

‘Hey!’ a voice called. A blonde girl in a black coat was stip-stepping along the wooden planking. ‘You can come behind us!’ she called out, and made a circular gesture. I eyed up the space between the high-tech fishing boat and the sticking-out tube, putted round in a circle and glided alongside. The girl leaned forward to take my line.

‘Thanks,’ I said.

She was a most improbable apparition to find on a pontoon on a March day. She had long blonde hair curving down over her face to hide one eye, and tumbling in carefully-crafted waves over her shoulders. Her skin was painted to porcelein smooth, the visible brow was gelled into a spiky shape, and her lashes were black as a ship’s funnel. Her lips were fashionably pale. She wore a painted-on red spangled dress under the open coat and heels which were completely out of place on a wood planks walkway.

She was, without question, Chloe, whose looks had taken Lizbet’s chances of stardom.

‘Thanks,’ I said again, and she gave a you’re welcome flip of her hand and sashayed back towards the flash fishing boat. A boyfriend? I was intrigued enough by the combination of her general looks and her obvious ease with boats to keep watching as I tied the Deuk up. She called ‘Aye aye’ into the boat, and a young man appeared.

He was no more likely than she was to be hanging around a fishing boat: a smooth-looking, polished man in his early thirties, ten years older than Chloe. His hair was cut smoothly to just above ear-length, and moussed in some way so that it curved out around his head from a centre parting. It gleamed in the light. Below it, he had dark brows and eyes, a thin line of moustache over full lips and a triangle of beard below them which ran down in a line to a curve around his chin. He was just taking off his oilskins – new, matching and an expensive brand – to show a white shirt and tailored trousers. He looked like a sooth-moother, and I was sure I’d never seen him before. Chloe draped herself over him and they kissed. I passed them with an ‘Aye aye’, the cats at my heels, and headed around the dinghy slip to the hard standing.

Out of water like this my little Khalida towered over me. She sat on her bulbed iron keel in a cradle cage, supported by six pads. Having been away from her made me see over again all that was needing done to her: antifouling, a good scrub of her white hull, new varnish on all the wood, repainting the decks, rewiring the guard rails.

Cat knew his own boat, even from this unfamiliar angle. He stretched his front paws . . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...