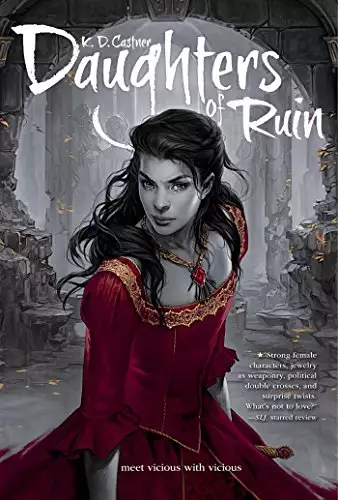

Daughters of Ruin

- eBook

- Paperback

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Game of Thrones meets Graceling in this thrilling debut that features four fierce princesses, “jewelry as weaponry, political double crosses, and surprise twists. What’s not to love?” ( School Library Journal, starred review). Rhea, Cadis, Suki, and Iren have lived together since they were children. They are called sisters. They are not. They are called equals. They are not. They are princesses…and they are enemies. Not long ago, a brutal war ravaged their kingdoms, and Rhea’s father was the victor. As a gesture of peace, King Declan brought the daughters of his rivals to live under his protection—and his ever-watchful eye. For ten years the girls have trained together as diplomats and warriors, raised to accept their thrones and unite their kingdoms in peace. But there is rarely peace among sisters. Sheltered Rhea was raised to rule everyone—including her “sisters”—but she’s cracking under pressure. The charismatic Cadis is desperately trying to redeem her people from their actions during the war. Suki guards deep family secrets that isolate her, and quiet Iren’s meekness is not what it seems. All plans for peace are shattered when the palace is attacked. As their intended futures lie in ashes, Rhea, Cadis, Suki, and Iren must decide where their loyalties lie: to their nations, or to each other.

Release date: April 5, 2016

Publisher: Margaret K. McElderry Books

Print pages: 320

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Daughters of Ruin

K. D. Castner

CHAPTER ONE

Rhea

First from the others was Meridan’s own

Lost a mother when she won a crown

Her daddy jumped up and defended the throne

Dance little queen, but don’t . . . fall . . . down.

—Children’s nursery rhyme

Rhea put up her hair as Endrit took off his shirt in the chamber below the private bedrooms of the castle.

Her maids were sent away.

The candles lit the room with warm halos floating a-pixie in the dark.

Rhea’s thick black curls took dozens of jeweled floral pins, stabbed in every direction, to stay aloft in the formal style.

As she fumbled in front of the full-length mirror, Rhea glanced at Endrit’s reflection. The years of assisting his mother in their training had made him the envy of all the noble sons at court, who seemed to be made of lesser mettle. Where the young lords would call for water and stop their coddled sword work at the first pain, Endrit had been the sparring partner—and punching bag—to the sisters, without the luxury of raising two fingers and storming off.

He was seventeen and looked like the flattering portraits hanging in the royal hall. Shoulders broad and tapering down across a barrel chest, and a taut abdomen. Rhea knew he kept his light brown hair a medium length because it looked soft and sandy when he lay under the trees in the orchards, regaling the swoony village girls with tales of castle comforts. And he knew it looked menacing when it hung wet over his obsidian eyes, in the heat of a fight.

After he pulled the linen tunic over his head, Endrit reached up and ran a hand through his wet hair. The third reason he kept it that length was to reach up and flex his arms and his abs and catch the princesses watching him in their mirrors.

Endrit smiled with mischief.

Rhea flushed and looked away. “Put your shirt back on,” she said.

“Excuse me, Princess, but it’s stifling in here. Some of us aren’t used to castle fineries.”

“Like clothing?” said Rhea.

“Like indoor heating,” said Endrit.

Rhea parried the jab with an unimpressed eyebrow. “Do you suffer a lot of cold nights, curled up with the old tabby cat?”

Endrit’s romantic exploits were the subject of endless teasing from the sisters . . . and endless speculation.

“I don’t know about that,” said Endrit. “Mrs. Wigglefoots never scratched so hard.”

Endrit turned to show a crosshatch of scars on his ribs stretching across the muscles of his back. Each was from Rhea, Cadis, Iren, or Suki missing their mark, swinging wildly, or losing control during their blade work over the years.

Rhea had no witty riposte.

The scars were deep and irregularly healed, as if some had been carved into already-scabbed tissue. Rhea remembered when she was first learning to throw her weighted knives, when she didn’t know to aim at the smallest target possible and was easily distracted. Endrit provided the human prey.

And if he wasn’t so skilled at diving clear, she would have skewered him a dozen times. As it was, she knew she was responsible for many of those graze marks along Endrit’s ribs. “Don’t feel bad, Princess,” said Endrit as he walked about the room, lifting the wooden dummies back onto their stands. “Some of these I remember fondly.” Endrit was the only one allowed to call the sisters “princess” in that puckish tone, and only in private. Rhea liked it when he did, because it made him feel like more than just the servant they had abused all these years so they could become masters of their arts. It made him feel like a friend.

Rhea finished with a last pin in her hair. Her head almost wobbled under the weight. Rhea didn’t spend any more time in front of the glass, not to admire herself as Cadis did. She simply used the glass to make sure her hair was ready for a royal ball and turned away. Not in disgust. Though maybe when she was younger. No, not disgust. Duty. Drive.

She was too busy to fuss about her thick mane or her inelegant posture. She was beautiful enough—though not as lovely as Cadis. And elegant enough—though not as regal as Iren.

Rhea caught herself thinking such thoughts and asked herself, And what about Suki? How do we measure against the youngest? Her answer was a welcome joke. She was certainly brave enough, but she would never be as wild as Suki.

Rhea straightened her red silk ball gown and said, “Aren’t you ready?”

“No,” said Endrit, lifting the last wooden dummy. “And neither are you.”

He threw a golden armband he had retrieved from the floor. Rhea caught it and clasped it around her left wrist.

It was a chunky piece of jewelry, made finer by delicate scrollwork patterns cut into the gold in the shape of a shining sun. It matched the elaborate necklace Rhea wore—the masterpiece of her family’s crown jewels. The lavish necklace began as a black lacy choker, set with hundreds of white diamonds all around and a giant ruby the size of an apricot at its center. Radiating from the ruby’s setting were long, thin, round black stones that tapered into impossibly sharp points.

When her father had first clasped the necklace around her neck on her thirteenth birthday, he’d told her they were the teeth of the crest-beast of their house—the onyx wyrm. It had been that evening after the shared birthday ceremony for all four sisters. Of course Rhea knew there were no dragons in the world, but she liked that her father told the tale as their ancestors would have, the way he had done when she was very young—before the war, before he had to treat her like her sisters, with no public sign of favor—like a bedtime story.

He looked at her in the mirror and she knew it must have been difficult for him, too. To pretend he had four daughters. To raise four queens—to pick up the burden their families had so recklessly dropped. She looked at him and saw a widower, a father, a great king. He was almost teary when he said, “You look a bit like your mother.”

As Rhea remembered the moment and stared into the same mirror as that evening, she touched the eight black diamond spikes that lay across her bare neck, reminding Rhea never to look down.

She was dressed for a coronation in full regalia. Nothing in the basement chamber shined as brightly as the crested sun-shaped ring on her right hand or the pointed dragon-shaped ring on her left.

Only Endrit and her father had seen her in ceremonial dress.

The wooden dummies stood around the open space in haphazard groups as if they were revelers at the grand ball. The walls of the basement space glimmered with weapon racks. A few punching bags hung in the corners. A replica of the throne of Meridan had been shoved to one side.

No windows.

No hearth.

Each of the sisters had her own private training room. It was Declan’s gift, a secret entrance leading down into a chamber below each of their bedrooms. Among the only things they didn’t share. Rhea was certain he had built the best room for her, though she couldn’t be sure. The sisters kept their rooms private. But she knew. She just knew. The girls had all run up to be the first to hug Declan. And as he hugged them back, Rhea had looked up, and her father had winked a conspiratorial wink. A sly and warm expression that said, We’ll keep the little secret between us. Of course, was it such a shocking secret that a father loved his daughter more than others? Rhea was sixteen now, and knew they were unlike any other father and daughter in the kingdom. And so, perhaps, their secrets were uncommon too.

Rhea stepped forward and bowed a very slight bow to Endrit.

He had put his shirt back on. He was dressed no better than a stable hand. He was no better than a stable hand. But, oh, terrible hells could he dance.

He stood tall and bowed deep, watching her the entire time. Rhea felt a shudder that rattled her earrings. Endrit opened his arms, holding them in the formal waltz position. It was an invitation every woman in Meridan would accept.

“Care for a dance, highness?” said Endrit.

The room was silent but for their breathing. Rhea imagined the royal musicians playing as they would the following night in the grand hall at the banquet of the Revels. She steadied her hands. It had to be perfect tomorrow.

Endrit laughed. “Oh, come now. The marquis isn’t worth a fright, is he? Should I slouch down, maybe snaggle up my face like he does?”

Rhea smiled, which threw off her concentration. Endrit swung his knees out into a bowlegged stance and twisted his lips into a sleazy grin. He made gross chupping noises with his lips. “Come now, my little sweet. Let me swing you around the room as only lovers do.”

“Ew! Geez!” said Rhea. “Does he say stuff like that?”

“I dunno.” Endrit shrugged. “Never met a prince before.” He continued to make awful smoochie faces. As she giggled at Endrit’s hideous caricature, Rhea felt her muscles relax. She breathed out and stepped into his arms, placed her hands into his.

Rhea looked up at Endrit’s dark eyes and said, “I have to kill you, you know.”

Endrit nodded. “And what if I kill you first?”

“Then you’ll ruin the Revels and they’ll probably hang you instead.”

“That is too bad,” he said. “I was beginning to like it here.”

Only twelve women in the world were capable of training in the grimwaltz of the high style, because it required two exceptionally rare traits. First, it required a country—or in the case of Maria Fermosa, a criminal cartel secretly running a country. Second, and more specifically, it required one of the twelve sets of crown jewels, crafted generations ago by a master of the extinct Grimlaw Smithy.

Legend had it that each of the weaponsmiths of the great guild created one set—manipulating precious metals and gems into deadly jewelry worthy of queens and weapons worthy of assassins. Rings with poison caps, necklaces with hidden garrote wires, bracelets suited as much for shielding against sabers as for displaying the elegant wrists of nobility. The empress of Tasan was known for a crown that folded inward into a buckler. Maria Fermosa’s corset was famously lined with diamond mail. “The better to help me sleep on the bed of knives my lieutenants like to set for me,” she’d say.

Each set hid its own secrets. “Surprise is the only weapon they all share,” said the master Grimlaw before he killed the eleven masters of his smithy and then himself.

The twelve crown arsenals passed down in the noble families, as did the martial art that governed their use. Just as monks of the steppe had created the art of wielding farm equipment to ward off mounted raiders and the magisters of Corent developed hand-to-hand warfare for the close quarters of the Academy spires, the grimwaltz, too, had a razor-sharp purpose. In formal state ceremonies, diplomatic parleys, and events of public address, the royals were the most exposed and the least armored. Born of the necessity to marry statecraft and spycraft, the tactical core of grimwaltz was defense of political assassination and preemptive murder.

The battlegrounds arose from the familiar settings: a throne, a feast, a dance.

Rhea held Endrit as they waltzed around the candlelit chamber.

Only queens trained with the crown jewels. But other forms of the martial art had spread among the commoners. Mothers would slip their daughters a razor bracelet before they went riding with a suitor. “Be happy, my love, but always take a bit of grim,” they’d say. “Just in case.”

The high style prized elegance and discretion over explicit warfare. Hundreds of years ago, the emira of Corent—Iren’s ancestor—was said to have kissed a would-be assassin on his cheek and injected a paralyzing toxin with the hand draped behind his neck. She sat him down. The musicians played on. No one saw him stiffen.

Rhea’s toe clipped over Endrit’s foot and she stumbled the next step. She cursed her own clumsiness.

“It’s okay,” said Endrit.

It wasn’t okay. Tomorrow was the Revels, when each of the sisters would perform for the crowds to showcase their training for the year. Cadis would fight like a typhoon and astonish them. Iren would flow as subtle and sublime as a zephyr, and Suki would shine like a wildfire.

As they traced an intricate pattern around the wooden dummies, Rhea asked, “Has Cadis polished her routine?”

They twirled a figure eight around two dummies that Endrit had arranged to look like a quarreling couple. Endrit smirked and looked away, as if sharing some joke with another partygoer. He was always the one that other men tried to impress—even if he was below them.

“Come on, now, Rhea,” he said.

“Come on, what?”

Endrit didn’t respond.

Rhea hated that. When he expected her to know things. And the knowing was somehow being grown-up enough to see things as he did. She hated it even more that she did know in this case. She knew he would have said, “I keep your secrets, Princess.” Meaning he’d keep the others’, as well.

Endrit lifted his arm to let Rhea take the inside turn under it. As her back was turned, Endrit reached behind him and pulled a thin filleting knife—of the kind Findish sailors used to cut rope and clean fish.

When Rhea whirled around to face him, Endrit kept the knife behind his back. With his other hand, he pulled her into his chest. He smelled like barn hay, sweat, and horse liniment.

This part of the dance was an intimate struggle between them. Rhea wanted to see what he held behind him, but Endrit thwarted the attempt. She stepped forward into the space that Endrit’s foot vacated. He held her in a cross-body lead, so that she faced in the same direction.

Her shoulders nested across his chest. She craned her neck upward to keep eye contact. She felt his breath waft over her lips.

They turned around the room. Any audience would see the blade glisten behind Endrit. But only sparring dummies shared the floor.

They stepped and cross-stepped, back and forth, feint and parry. With his firm hand on her lower back, Endrit always managed to turn Rhea before she could see the knife. They tangled and clutched, until finally the moment they both knew was coming, when the flautist would stand for a trilling climactic solo, and Endrit sent Rhea into a wild free spin toward the middle of the floor.

Rhea twirled at the center of the chamber hall with one arm above her head like an automaton in a music box. Her other hand rested on the ruby brocade hanging from her neck. She felt her skirt billow and corrected her balance for the weight of the sparkling jewels she wore. Her back arched. She spun on the ball of her foot and felt graceful for the first time all night.

And more than anything, she felt watched.

As Rhea straightened out of the spin, she lowered her arm. Endrit extended his hand and she took it. They knew the flautist would hit a note at this point that sounded like a goldfinch being crushed in a doorjamb.

Endrit reeled her in. She spun toward him. As she did so, Endrit lifted the knife and stabbed just as Rhea turned in to his arms.

The knife whistled downward.

It clanged on the ruby brocade, nestled in Rhea’s palm. The delicate gold chains strapped it around her fingers so that it held firm—and armored the inside of her left hand.

The tip of the fillet knife found a socket in the brocade to stick itself.

She stared at Endrit.

He whispered, “You’ve got this. Fight speed.”

Rhea’s hand shook, holding off the pressure, until she wrenched her hand and sent the blade scudding across the stone floor of the chamber.

In the same motion, she pivoted her hips and dug a right hook into Endrit’s ribs.

He grunted and let go.

Rhea dashed away, to a safe distance.

In the moment’s reprieve, Rhea made a formal ready position and inserted the point of the dragon ring on her right hand into the well of the sun-shaped ring on her left. With a twist, the head of the dragon punctured into a compartment of the sun ring and coated the tip in corkspider poison.

Endrit bored down on her with clenched fists. He opened with a left. Rhea smacked it down with the brocade in her open palm. He winced as his knuckles cracked on the stone. He swung with a heavy right. Rhea ducked under and punched twice on the same rib as before. This time she pulled short before stabbing him with the poisoned ring.

Endrit staggered back.

But not long.

He lunged with a vertical knee and caught Rhea’s chin in her crouched position. Rhea’s eyes flashed white. This part always hurt at full-contact fight speed.

Rhea moved with the impact and hit the ground at a midroll.

She scrambled behind a dummy to buy time to regain her footing and to reach for a hairpin. As Endrit approached, she flicked her hand and launched two of the weighted pins at his face. Endrit lurched sideways.

The darts planted into the face of the dummy.

The audience would understand the dummy was a stand-in for the attacker. Already, between the poison ring and the darts, she had killed two would-be assassins.

Endrit strode forward, reached down, and grabbed a broadsword from the belt of a dummy. Without hesitation, he marched toward her, raised his sword, and struck down across her body.

Rhea dove under the angled blade. She followed the motion into a sideways somersault. She ended in an alleyway formed by dummies standing in two rows. Endrit pressed the attack. He dashed around the dummies to one end of the rows.

His heavy blade would be carried only by soldiers or royal guards attempting to kill her, a simulation of the ultimate betrayal and a grim reality—the possibility of her own bodyguards turning coat of arms.

Her father used to whisper, “Even our men. Even Endrit or Marta. If they turn, you put them down like rabid dogs.”

She couldn’t blame him for worrying. It was betrayal and assassination that had taken the last king and queen of Meridan. She knew he was determined never to let that happen again. In the advent of such a paranoid outcome, Rhea would be woefully disadvantaged, just as she was now, with Endrit approaching.

Rhea gave ground and reached for more throwing blades. More and more locks of her hair tumbled onto her shoulders as she pulled the pins and sent them flying at Endrit.

He marched inexorably forward.

She showed off her precision. It had gotten even better over the last year.

Dummies on either side of Endrit sprouted gems between their eyes as he approached.

A whole unit of blackguards, dead.

Rhea stood at the end of the row.

Endrit closed the distance and swung again.

This time she caught it up high, early in the swing, with the side of her thick bracelet. A delicate shield for hacking blades.

Endrit slashed down again and again.

One.

Two.

Three.

Rhea counted in her head.

High block.

Step back.

Low block.

Step back.

The blows made her entire arm jolt. On the last step, she had a disarm maneuver that was new to the routine, the one that could maim both of them if she failed.

Don’t falter. Don’t falter, she thought.

Endrit swung the sword sideways at her neck, like a scythe cutting the heads of wheat. Instead of deflecting the strike, Rhea stepped to meet it. She blocked with her inner forearm—bless the smith for making her bracelet strong. When the sword clanged on her bracelet, Rhea followed it with her left hand and hit the blade up by the hilt with the brocade in her open palm.

The sword twisted between the two opposing forces and wrenched out of Endrit’s grip. The blade caught Endrit’s shoulder, slicing the tunic as it flew off, clattering on the stones.

Endrit winced, but he didn’t drop a step.

He grabbed Rhea around the neck, just above her choker.

She pulled two of the black stone sunrays from her necklace and made the motion of stabbing just inside his collarbone on either side.

Endrit let go, as any assailant would have been dead by then.

They moved into the big finish: a series of sparring drills where Endrit attacked from every direction—swinging wildly, changing forms from the Corentine ridge-hand to Tasanese grappling. Rhea exhausted the rays of her sun necklace, cutting off kicks at the knee, meeting “vicious with vicious,” as her father would say.

She was an exhibition of cold, efficient, and most of all, lethal control. That was the heart of grimwaltz and the heart of a ruler, after all—control.

The dummies in the dark room each found a new way to die.

The wound on Endrit’s shoulder bled.

The left side of his tunic was nearly soaked.

The final stunt was a subtle routine that began with Endrit grabbing Rhea’s wrists. Some of Marta’s best choreography. Rhea stepped out to break Endrit’s balance and twisted her hands around to grab his wrists. They struggled for leverage.

The music the next day would swell—every stringed instrument in full volume. Then, just as abruptly, the music would drop.

Rhea and Endrit straightened, hand in hand.

They were back in waltz position as if nothing had happened.

Except now Rhea’s curls were untamed and unbearably hot. Her hands still shook, twitch reflexes still set to caution. Endrit’s tunic was a sopping rag—sweat and blood. He said, “Well done,” but his grimace gave him away. He was hurt.

The chamber was a slaughterhouse strewn with two-dozen dummies—stabbed, poisoned, or crippled.

They each stepped back, bowed, turned, and bowed again to the pretend audience.

Rhea instinctively angled her bow in the direction where her father would be sitting—the king’s balcony of the Royal Coliseum.

The instant they finished, Rhea rushed to Endrit’s side. “I’m so sorry,” she said, helping him take a seat.

Endrit took the help, but didn’t seem to need it.

“Don’t worry. That was perfect.”

“I cut your shoulder open.”

“They want realism. Your dad would have loved it.”

Rhea paused a moment from examining the shirt.

“You think?”

“I’m telling you, Princess, it was perfect.”

Rhea took a moment to relish the idea of gaining back the honor she had lost after the Revels of the previous year. No one told her she had lost it, but she saw it in the eyes of the king and in the way Marta patted her on the shoulder and said, “Good work. Learn from this and you’ve won.”

She only ever said that to the loser.

Rhea had certainly lost her sparring exposition to Cadis. In front of all the nobles of Meridan, Rhea had dropped to a knee before the future queen of Findain. It may as well have been surrender—a banner that read THE BLOOD RUNS THIN IN MERIDAN KEEP. The entire crowd had been stunned. Her father, who loved her—she knew he loved her—still couldn’t hide his disappointment.

It wasn’t his fault. Rhea knew she had caused him endless jibes in the court of public opinion. Rhea had subordinated the house of Declan to a bunch of treacherous Findish merchants in one clumsy step.

She heard a voice.

Endrit’s.

Rhea snapped out of her memory to see his obsidian eyes peering at her.

“Where’d you go, Rhea?”

“Nothing,” said Rhea. “Take your shirt off.”

Endrit laughed. Rhea added, “So I can see your cut, you dandified peacock.”

“Of course,” said Endrit. “And anyway, to the victor go the spoils.” He gave a cheeky grin.

Rhea rolled her eyes and helped him pull the sleeve so he didn’t have to move his left shoulder. The cut was shallow. It would be scabbed by tomorrow.

“We have bandages in the outer hall,” said Rhea.

“We’re done? Are you saying all I had to do was stab myself?”

Rhea pressed down on Endrit’s shoulder. He howled with laughter and pain.

“You’re lucky we got it perfect,” said Rhea, standing. “Otherwise I’d make you go until you bled out.”

“A noble way to die. I’m sure there’d be a royal funeral.”

“A royal funeral? Ha! We’d flop you down behind the barn,” teased Rhea. She left the jewels scattered around the private chamber: the pins stuck in the dummies, the blades of the sun necklace embedded in several wooden posts. She’d return the next morning.

“I suppose that’s fair enough,” said Endrit. “That happens to plenty of royals too.”

When Rhea and Endrit walked into the common hall that connected the rooms of the four queens, Rhea was disappointed to find her sisters and Marta there, thus ending her privacy with Endrit. And Rhea’s sisters seemed disappointed to see a shirtless Endrit—not because of his partial nudity, but because he was in that state with Rhea.

The six-sided room had one door on every wall—four leading to the queens’ rooms, one coming from the throne room, and one for the servants to use coming from the kitchen.

At the center of the room sat a giant round oaken table large enough to seat fifteen and sturdy enough to stage a Tasanese circus. The sisters ate their meals at the table, studied there for Hiram’s exams, and on nights such as these, when they couldn’t sleep, they convened around it to while away the hours.

Cadis had been regaling them with an improvised tale of Rusila, the Maid Marauder, something about winning a race to a treasure by lashing her ship to the back of a sea dragon. Only Suki had been listening, as she lay on her back in the middle of the giant table, throwing an iron ring up to the vaulted ceiling between the segments of the chandeliers and catching it on her feet.

Iren and Marta sat together on the far side. Before them were several sheets of stained glass. Iren used a long steel cutter that looked like a fountain pen, with a diamond tip, to cut intricate shapes into the glass. Marta used Iren’s nippers to snap the cut pieces out of the sheets.

At first blush, it looked like she was making an elaborate set of wind chimes in the old Corentine style. The spires of her home were famous for decorative glasswork, situated as they were in the windy mountains, above the cloud line. The Corentines admired the elegant and delicate work. Many of the balconies of the Academy spires were hued of colored glass.

When Rhea and Endrit entered from the bedroom, everyone stopped—the storytelling, the juggling, the glasswork.

In that short instant, as Rhea weighed all the disappointment in the room, she couldn’t help but feel hurt. Hers was not malicious. She just wanted more time with Endrit. Why shouldn’t she? But theirs, well, their disappointment was because they wanted to spend less time with her.

Marta stood up when she saw Endrit bleeding. The pliers in her hand fell to the table. Just as quickly Marta controlled herself, as she always did. She wouldn’t embarrass him by doting over it. But for the slightest of moments—every time one of them injured her son—they would see the shadow of outrage pass over her.

“What happened?” said Marta in a controlled voice.

Only then did Rhea realize she was in bigger trouble than she’d thought. She had summoned Endrit to her chamber after-hours. She had continued to train at full contact, though they all knew that Marta forbade training the day before the Revels, to give them time to mentally prepare. And she had cut a bleeding gash into her son’s shoulder.

Rhea’s answer caught in her throat.

To her eternal gratitude, Endrit stepped forward. “This? This is nothing,” he said.

“How did it happen?” said Marta.

“Game of checkers,” said Endrit, gr

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...