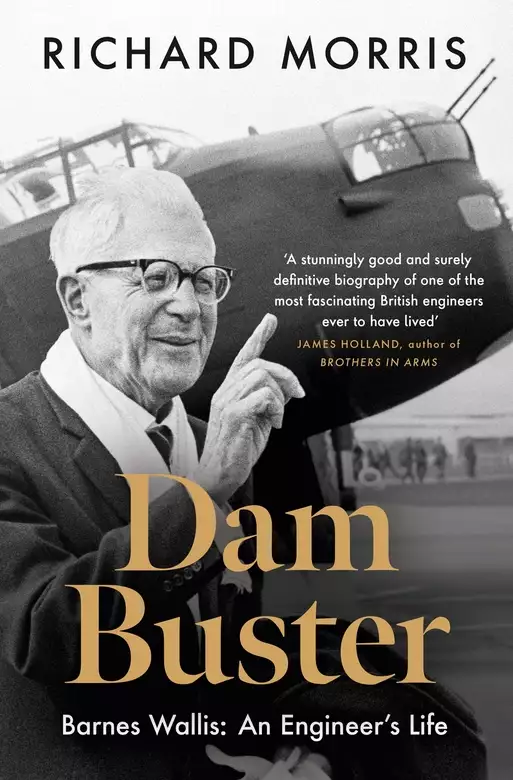

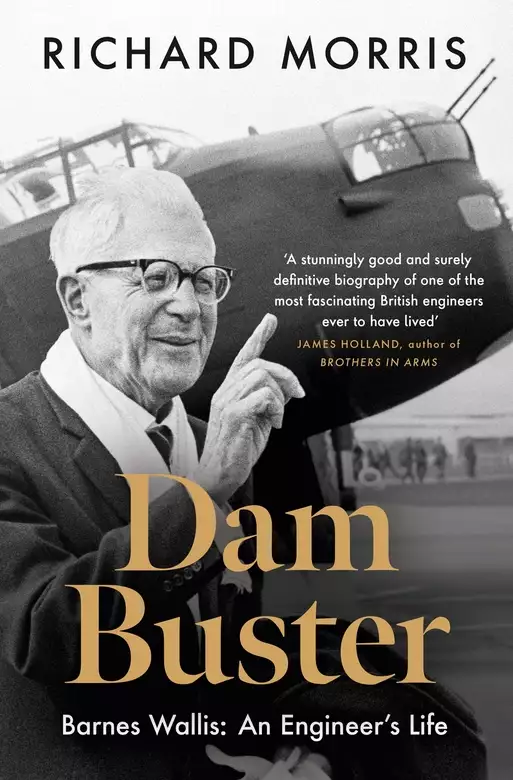

Dam Buster

- eBook

- Audiobook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Barnes Wallis became a household name after the hit 1955 film The Dam Busters, in which Michael Redgrave portrayed him as a shy genius at odds with bureaucracy. This simplified a complicated man.

Wallis is remembered for contributions to aviation that spanned most of the 20th century, from airships at its start to reusable spacecraft near the end. In the years between he pioneered new kinds of aircraft structure, bombs to alter the way in which wars are fought, and aeroplanes that could change shape in flight. Later work extended to radio telescopy, prosthetic limbs, and plans for a fleet of high-speed cargo submarines to travel the world's oceans in silence.

For all his fame, little is known about the man himself - the confirmed bachelor who in his mid-30s fell hopelessly in love with his teenage cousin-in-law, the enthusiast for outdoor life who in his eighties still liked to walk up a mountain, or the rationalist who dallied with Catholic spiritualty. Dam Buster draws on family records to reveal someone thick with contradictions: a Victorian who in his imagination ranged far into the 21st century; a romantic for whom nostalgic pastoral and advanced technology went together; an unassuming man who kept a close eye on his legacy.

Wallis was last in a line of engineers who combined hands-on experience with searching vision. Richard Morris sets out to locate him in Britain's grand narrative.

Release date: August 22, 2023

Publisher: Orion

Print pages: 416

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Dam Buster

Richard Morris

A&AEE: Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment

ACAS: Assistant Chief of the Air Staff

ACAS (Ops): Assistant Chief of the Air Staff (Operations)

ACAS (TR): Assistant Chief of the Air Staff (Technical Requirements)

Air Cdre: Air Commodore

ADGB: Air Defence of Great Britain

AHB: Air Historical Branch

AM: Air Marshal

AVM: Air Vice-Marshal

AOC: Air Officer Commanding

ARC: Aeronautical Research Committee

Baseball: Proposed water skipping munition to be fired at warships from motor torpedo boat

BLEU: Blind Landing Experimental Unit

BRS: Building Research Station

CAS: Chief of Air Staff

Catechism: Air operation against the warship Tirpitz, 12 November 1944

CCO: Chief of Combined Operations

Chastise: Air operation against German dams

C-in-C: Commander-in-chief

CID: Committee of Imperial Defence

COS: Chiefs of Staff or Chiefs of Staff Committee

CRD: Controller of Research and Development

Crossbow: Operations against V-weapons

D Arm D: Director(ate) of Armament Development

DB Ops: Director(ate) of Bomber Operations

DCAS: Deputy Chief of Air Staff

DD Arm D: Deputy Director, Armament Development

DD/RD Arm: Deputy Director, Research Directorate Armaments

DDSR: Deputy Director of Scientific Research

DELAG: Deutsche Luftschiffahrts-Aktiengesellschafft (German Airship Travel Corporation)

DMWD: Department of Miscellaneous Weapons Development

DSR: Director of Scientific Research

Emulsion: Project to develop streamlined casing for Britain’s atomic bomb

FAA: Fleet Air Arm

Fg Off.: Flying Officer

Flak: Fliegerabwehrkanone – anti-aircraft artillery

Flt Lt: Flight Lieutenant

g: Value of gravitational acceleration at sea level

Golf Mine: Family of water ricochet munitions ascending in weight and size from Baseball through Highball (Light), Highball (Heavy) to Upkeep (for all of which q.v.)

Grand Slam: Eventual codename for Tallboy L (q.v.)

Green Lizard: Early form of missile derived from wing controlled aerodyne Wild Goose (q.v.)

Grouse Shooting: Trials to test use of Highball against railway tunnels

Grp Capt.: Group Captain

GWR: Great Western Railway

H2S: Ground-scanning radar fitted to Allied aircraft

HAA: Heavy anti-aircraft (artillery)

Heyday: Rocket-powered torpedo

Highball: Water ricochet weapon. Highball (Light) was originally envisaged for use against lock gates, submarine shelters, beach defences and naval units. Highball (Heavy) was intended for Italian multiple arch dams, merchant ships, canal locks and hydro-electric barrages

Jabo: Jagdbomber – fighter-bomber

Kurt: Spherical bouncing mine developed by Germany

LAA: Light anti-aircraft (artillery)

LDV: Local Defence Volunteers (later, Home Guard)

Lt: Lieutenant

LZ: (of German airship) Luftschiff Zeppelin

M: Mach number

MAEE: Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment

MAP: Ministry of Aircraft Production

MEW: Ministry of Economic Warfare

MI5: Security Service with UK domestic remit – from Section 5 of the War Office’s Directorate of Military Intelligence (1916), having previously (from 1909) been a branch of the Directorate of Military Operations

MOS: Ministry of Supply

MU: Maintenance Unit

NACA: National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (US)

NASA: National Aeronautics and Space Administration (US)

NPL: National Physical Laboratory

Obviate: Operation against the warship Tirpitz, 29 October 1944

OC: Officer Commanding

OR: Operational Requirement

ORB: Operations Record Book

Oxtail: Projected Highball operation against Japanese fleet

Paravane: Operation against the warship Tirpitz, 15 September 1944

Plt Off.: Pilot Officer

R, r: (of UK airships) Rigid

RAAF: Royal Australian Air Force

RAE: Royal Aircraft Establishment

RD(T): Research and Development (Technical)

RAeS: Royal Aeronautical Society

RRL: Roads Research Laboratory

SABS: Stabilised Automatic Bombsight

SEAC: South-East Asia Command

Servant: Intended air operation against warship Tirpitz using Highball

SHAEF: Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force

SIS: Secret Intelligence Service, MI6

Source: Submarine operation against Tirpitz, September 1943

Speedee: US codename for inert Highball

SPOG: Special Projectile Operations Group

Sqn Ldr: Squadron Leader

SS: Submarine (or Sea) Scout

Swallow: Wing controlled aerodyne in development 1953–59

Tallboy L[arge]: 22,000 lb deep penetration bomb

Tallboy M[edium]: 12,000 lb deep penetration bomb

Tallboy S[mall]: 4000 lb deep penetration bomb

TR: Technical requirements

TRE: Telecommunications Research Establishment

Upkeep: Water ricochet mine for use against gravity dams

Wg Cdr: Wing Commander

Wild Goose: Wing controlled aerodyne in development 1946–53

My first thanks go to the late Barnes Winstanley Wallis and Mary Stopes-Roe for their invitation to write this book, and for the unlimited access to family papers that has enabled me to do so. For advice, encouragement and help of many, many kinds in the years that followed I thank Nicholas Bennett, Sebastian Cox, Eddie Crouch (clerk to Effingham Parish Council, 1953–2003), Bob Cywinski, Robin Darwall-Smith, Douglas Denny, Colin Dobinson, Anna Eavis, Peter Elliott, Elisabeth Gaunt, Martin Giles, Chris Henderson, James Holland, the late George Johnson, Nikki King, Axel Müller, Robert Pawson, Frank Phillipson, Martin Pickard, Anthea Pratt, Peter Rix, Alan Spence, the Earl Spencer, David Stocker, Cathy Stopes, Christopher Stopes, the late Harry Stopes-Roe, Helena Stopes-Roe, Jonathan Stopes-Roe, Heather Thorn, the late Richard Todd, and Kathryn White.

For assistance in archives and access to collections I thank the Airship Heritage Trust; BAE Systems Heritage; John Cochrane; staff and volunteers of the Brooklands Museum; the Manuscripts Department of Cambridge University Library; trustees of the Barnes Wallis Foundation; the Dock Museum, Barrow-in-Furness; East Riding Archives; Sue Morris and the Effingham Local History Group; Gina Hynard and the Hampshire Record Office; Collections of the Imperial War Museum; the Special Collections of the Brotherton Library at the University of Leeds; London Metropolitan Archives; The National Archives; the Royal Aeronautical Society; the Archive Collection of the Royal Air Force Museum; Doug Stimson and his colleagues at the Collections Centre of the Science Museum, Wroughton; Bethany Radcliff at the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin; the Estate of Mary Stopes-Roe; the Surrey History Centre; and Tyne and Wear Archives and Museums.

Robert Owen, historian of the 617 Squadron Aircrew Association, was throughout a wise sounding board, and at times acted also as unpaid research assistant in Cambridge University Library and the Collections Centre of the Science Museum. I am thankful, too, for the critical alertness of Anne Deighton and Jane Morris, who with Robert read the book in its successive drafts and did much to improve it.

Authors write; publishers produce; for all kinds of productive expertise I thank Kate Moreton, Natalie Dawkins and Lucinda McNeile.

Richard Morris

December 2022

Barnes Wallis was God-fearing, romantic, an English exceptionalist, a doting and patient son, a proud grandfather, at times a self-mythologising martyr, and a creator who approached each task from first principles. Upon what does his reputation now rest?

Many would say that he owes his place in national memory less to the significance of things he made than to their place, and his, in the way they are remembered. English popular culture and political life are awash with nostalgia for the Second World War.1 Upkeep and the deep penetration bombs seem to epitomise a legend of British scientific and inventive prowess in which Wallis provided the RAF with a succession of wonder weapons, each of which arrived in the nick of time to save Britain from some new threat and shorten the war. On this basis, he owes his standing more to 1950s mythologising and cultural memory than to historical assessment. But if we put that to one side, what does historical assessment say?

The R80 and R100 broke new ground in airship design and technology. R100 was arguably Britain’s most successful passenger airship and was all the more notable for having been built (in John Anderson’s words) on a shoestring. If there were drawbacks, they sprang from limitations of the materials then available and frailties of the airship genre itself. The legacy of R100’s gas cell wiring can be followed through geodetics and on into the Parkes radio telescope.

Geodetic construction was a waypoint in the evolution of aircraft. Looked at backwards it was a blind alley, but in the 1930s it liberated design from the truss frames upon which aero engineers had hitherto relied and offered unheard-of performance. In 1939 the Wellington had some 40 per cent greater range than any other bomber in the RAF; in 1945 it was the only British bomber still being built that had been in production before the Second World War began.

Wallis’s wartime work on weapons is summed up by Harris. Having called Upkeep ‘tripe’ in February 1943, a year later he answered the question with which this book began by saying there ‘were few civilians whose direct personal contribution to the war had been greater’.2

After the war Wallis generated ever more remarkable ideas. He did not invent the concept of variable geometry, but he was its main flagbearer during the mid-1950s when interest in it was at a low ebb. It was he and his team who sustained awareness of the form and showed that it was workable. Internationally, it has been noted that while some historians of aeronautics have acknowledged this pivotal role,3 others have either downplayed it or cut him out of the story altogether.4 A more fundamental point is that the unique aspects of Wild Goose and Swallow – no tail, differential sweep – were never realised at full scale. We know these aerodynes were aerodynamically viable, but as in the case of his late ideas – the square fuselage, isothermal flight, the Universal aircraft – it is difficult to point to the heritage of original concepts that have yet to be tried in the roles for which they were intended.

What of the received story of a patriotic genius who offered visionary ideas to his country and was snubbed by post-war governments? That story was led by Swallow, his most charismatic aircraft. Like most of his creations it was not beautiful, but it had rare presence. Swallow’s dramatic arrowhead also fed narratives, repeated in Parliament and the press, spanning the eras of Macmillan and Wilson, that by discarding it Britain had taken a wrong turn, and that Britain had gifted one of its best ideas to the Americans who then sold it back to Britain.5

The main reasons why the post-war ideas went unrealised were the lack of politically and industrially fundable formats and timescales into which they would fit. Wallis’s heart was set on civil transport several generations ahead, whereas the Cold War demanded prioritisation of military projects and fostered demand for near-term, guaranteeable results. Wallis’s department was too small properly to scale up his ideas; the production side of Vickers was focused on commercial work and government contracts; Wallis and Edwards were often at loggerheads; towards the end, the BAC was content to indulge his experimental work while getting on with mainstream projects. He was not always his own best advocate. His impatience could alienate those who tried to help him;6 his optimism occasionally bordered irrationality. His obsession with creation and grasp of the bigger picture repeatedly led him to pursue an idea wherever it led, and thereby outside his conventionally allotted role and into someone else’s. His interdisciplinarity and friction thus went together, and because of that, at times, there were some who responded by seeking to downplay his worth.7

Iain Murray reminds us that whereas some inventions (like the jet engine) will come about sooner or later regardless of whether particular individuals are behind them, others depend on particular people because they are non-imitative and stem from original thought.8 Wallis was an original thinker, and as his story has shown, originality brings risks: a task can be approached either through the improvement of an existing solution or through something new, and as Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527) pointed out, nothing is ‘more dangerous to handle’ than to initiate something new.9 But leaving it there would miss him entirely. Wallis lived not only for creation but through it. If an idea went unfulfilled it was still an idea. Behind all the particularity and intermittent grousing he was a joyful man. In October 1959, he mused that a stranger reading his fifteen-year cycle of unsent letters would come away with an impression of toil and disappointments – yet the concept of Cascade had just been revealed, and he was buoyant.

On and on, always some New Thing springing up, full of promise, meeting or avoiding all of the old difficulties.10

Or back in 1923, joining Burney:

Besides, Molly, it’s the most wonderful work in the world … You see it’s all new, and one is thinking out new things all the time.11

Or Swallow, his Unknown Symphony:

Laus Deo, and again, Laus Deo, what a life, what a World.12

Edith Eyre Ashby and Charles Wallis, both twenty-six, married in the church of St John, Woolwich, on 9 September 1885.

Edie was from an affectionate family that had pioneered progressive education. Charles was a medical student, one year short of qualification. His mother had died twelve days after his birth, whereafter his father George, a clergyman, delegated his upbringing, first to his dead wife’s grandparents and then to the rector of a remote parish in Lincolnshire. His education was supported by £2000 left in trust by a grandfather, Joseph Robinson. The costs of a new household and wife made inroads into what was left of these funds. Edie was uneasy, the more so when in November she realised she was pregnant. Next June, unease turned to panic. Some of the remaining trust money had been invested in India; ten days after the birth of their son, John, Charles told her that the company had gone into liquidation.1

Charles achieved membership of the Royal College of Surgeons in the same month. In the autumn he sat for the diploma of Licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians and passed. He was now qualified but lacked the means and connections to join a practice in London. Charles accordingly accepted a post as assistant to Dr Josiah Allen, district Medical Officer and Public Vaccinator in the industrial town of Ripley, east Derbyshire.

As 1886 neared its end an unexpected Christmas card arrived: ‘To Edith and Charlie from Uncle Barnes and Aunt, with love and best wishes.’ ‘Uncle Barnes’ was Lt Col. Barnes Slyfield Robinson, Charles’s mother’s brother. Until then they had heard little from him, mainly because he had usually been somewhere else enforcing Britain’s colonial will. Barnes’s regiment, the 89th Regiment of Foot, had fought in the Crimean War where he had served during the siege and fall of Sevastopol in 1855. The regiment then moved to Cape Colony (in what is now South Africa), there countering a rising by the Xhosa, followed by eight years in India that included service during the Indian Mutiny. Since then there had been another tour in India and Burma. By 1886 Barnes was living in Dover.

Early in the New Year Edie recorded that she was again in an ‘interesting condition’. The second child was born soon after 3 a.m. on Monday, 26 September. It was a quick labour, and the baby slept later in the morning. Edie’s mother was there to assist and described the newcomer to her eldest daughter: ‘a nice plump little man – weighs 8lbs – at present is very red and has a lot of darkish hair with a largish nose somewhat like the Father’s. In fact, I think it will resemble Charlie very much’.2

Names were aired. One was Victor (Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee had just been celebrated). Another was Edward Neville Wallis, after Edward Ashby, Edie’s favourite uncle, and Neville Frewer, a medical friend of Charles, both of whom were to be godfathers. Edie, however, was superstitious about Edwards: two relatives with that name had died young, and her sister Maria – to be godmother, but then away in India – knew of two more. Then came news that Uncle Barnes was poorly. Barnes was Charles’s last living link to the mother he had never known; on 25 October a telegram told that he was dying. Edie wrote at once to her sister Lily:

Charlie is much cut up. Col. Robinson was the last left of his mother’s family, and though Charlie saw so little of him, from that link to the past, I know he was sincerely attached to the little gentleman. I am so glad I wrote and told him Neville was also to be ‘Barnes’.3

Tuesday, 15 November was chilly, with a north-east wind, bright intervals, and flurries of snow. Early in the afternoon Edie held her new son and stepped up to the font in the church of All Saints, Ripley. George Wallis had received permission from the vicar to take the service. He dipped his hand in the water and said, ‘Barnes Neville, I baptise thee in the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost.’

Edie was the third daughter of John Eyre Ashby (son of a City grocer, an astronomer and dissenting minister) and Maria Smith (daughter of a coal and corn merchant). Her elder sisters were Maria Eyre Ashby (b.1849), known as Minna inside the family, and Elizabeth Eyre Ashby (b.1852), known as Lily.

In 1855 John and Maria bought a school. Its premises were a large Georgian house in Enfield called Gothic Hall, where young gentlemen were prepared for the Civil Service of the East India Company, military colleges and universities.4 Gothic Hall was a good place for young people. It had attics for hide and seek, roofs down which to slide, and a summer house roof on which to climb. In the grounds were forks of apple trees in which to perch, a walnut tree canopy, and beeches yielding nuts for which you could forage in autumn. Around the house were pet rabbits, guinea pigs, cats and dogs. There were hay parties (in which you were buried in hay), Christmas tree parties, expeditions into Epping Forest, and fireworks. John Ashby had a telescope through which the boys could study the moon, stars and the Great Comet that appeared in 1860. A natural science table bore a spectroscope, magnetic boxes, a skull, a Roman intaglio, and prehistoric flint tools.

Edith Eyre Ashby was born into this blooming environment on 17 March 1859. She was coddled by the boys, who admired her blue eyes and golden hair and noted her enthusiasm for animals in preference to dolls. As the sisters grew, differences of temperament emerged. Minna was calm and affectionate. Lily, energetic and generous, could also be explosive – bitten pillows, thumped walls. Edie was precocious and excitable.

The happy times ended in late 1863 when John Ashby succumbed to Bright’s disease and died. Maria sold up and moved to Brighton to start a school of her own. They called it Enfield House, in memory of John, and it opened with six pupils in the autumn of 1864. Enfield House did well enough as a school but was borderline as a business, and as years passed Maria became careworn. Minna worked as her assistant until 1870, when she married. Lily likewise taught until she too married. Both husbands were former Gothic Hall boys with whom the Ashbys had kept in touch. Minna’s young man was Tom Francis, now a solicitor. Lily’s marriage was to Theo Maxwell, who had studied medicine, and after qualification served as an ambulance officer in the Franco-Prussian war. Both couples moved to India, Tom to be legal adviser to the Maharaja of Dabhanga in Bihar, Theo as a medical missionary.

Minna, Lily and Edie were ardent letter writers. Lily told of long treks in the mountains of Kashmir, of poverty and beauty. Minna described moments of imperial grandeur, like the launch of Victoria, the Maharaja’s lake steamer, and of tragedy, like the death of her third child.

Edie took singing lessons, worked hard at the piano, and played chamber music. She loved her animals, which included rats (‘I think of giving them away, and am looking for an eligible person’), birds and hens. In that enthusiasm, however, was a kind of acquisitive carelessness which saw creatures of any kind as existing for her pleasure. She took creatures into captivity regardless of what they were or how, even whether, they could be kept. Her letters are full of chatter about their anthropomorphised personalities.

In 1877, Maria Ashby decided to close Enfield House. Edie was now eighteen, the age at which young women put their hair up. Her journal suggests someone assured, talkative, given to adolescent high spirits and flirtatious fun, but also to self-reproach over her lack of devotion. Before they left she went into the garden to look at old nooks where ‘I used to build fairy palaces of mud’ with spent matchsticks as little men. The garden was now overgrown with briar and meadowsweet; she recalled places where sunshine had fallen, or where the wall would be in shade: ‘At such points I would hang my bird’s cage, that poor old Dick might be happy as long as possible.’ ‘Ah well! I suppose now begins my real woman life. My old associations are all to be broken up, everything will be new.’

Lily and Theo, back from India, were setting up a practice to serve the middle classes around Woolwich Common and staff of the Royal Military Academy. They bought a large house on the edge of the Common, and in April 1878 Maria Ashby and Edie joined them. The following month, Minna arrived with her three children and a fourth in her womb, for whose birth she had returned. Lily herself was in the last weeks of pregnancy and gave birth to a daughter a fortnight later.

For a few months, then, most members of the family were back under one roof, Theo’s prospects looked good, and Maria was surrounded by her grandchildren. But there were shadows. Lily’s child died the following January, and when Minna returned to India in November 1879, it was in the knowledge that her husband Tom had begun to drink, and without her eldest sons. It was the British custom in India to send boys home for schooling when they reached seven or eight. Thomas (known as Taf) and John (known as Jef) were now left behind and sent to boarding school.5 When Minna said goodbye to Jef, he ‘did not know I was looking my last on him for long years.’

Thus did things stand when seven months later a young medical student called Charles Wallis was shown into Theo Maxwell’s drawing room. Charles was born in January 1859 at Paglesham, a fishing community in eastern Essex, where his father was curate. At his baptism he was given the names Charles (after a maternal uncle), George (after his father) and Robinson, the maiden name of his mother, Anne Georgina, who had died of a postnatal infection three days before.

Both grandparents came from military families. George’s father was a purser in the Royal Navy, Anne the daughter of Major Joseph Robinson of The King’s Royal Rifle Corps and Anne Bowles, of Dublin and Chester. The Robinsons were in their sixties, and it was to them that George turned for the care of his motherless son. Charles lived with them until he was six, whereupon he was put into the care of the Rev Henry Owen and his wife Catherine at Truthorpe, an agricultural parish of some 300 souls on the Lincolnshire coast, where Henry was rector.6 It was here, rimmed by wide skies, among fields of beans and turnips, overlooked by brick windmills, lapped by the sea along the long ribbon of Trusthorpe’s beach, that he spent the next six years.

The Owens had children of their own, and there was another boarder. Amid the bustle, Catherine did what she could to mother the outsider. Charles’s memories of himself as a solitary boy skating along frozen dykes on winter afternoons, pole-vaulting over ditches or wandering among the stumps of prehistoric trees revealed by neap tides were all of a piece with a conviction that he had been banished. This is possible: when George Wallis married Caroline Millett, the daughter of the rector of Lyng, Norfolk, in 1863, Charles was not at first invited to join them.

George Wallis was short and stubby, hot-tempered, with a squarish face framed by mutton-chop whiskers. He was a man of idiosyncrasies which included an insistence on bristly Jaeger woollen underwear, nightshirts, and pillowslips; a personal egg-boiler fuelled by a charge of methylated spirit sufficient to boil one egg; reliance upon fermented goats’ milk as a remedy for all ailments; and a system of ropes and pulleys of his own devising for hoisting the trunks and hatboxes of visitors to upper floors. His fiercely evangelical outlook was reflected in long sermons wherein torture loomed large, and daily family prayers in which the sins of those present were closely examined. George disliked anything that smacked of ritualism, such as flowers on an altar, insisted that the word ‘God’ be spoken softly as ‘Gawd’, and that each time it was written it had to be with a new pen nib. He was obsessive about words. A mispronunciation by a young relative was likely to trigger an on-the-spot lecture about its articulation and etymology. As he grew older and his hearing failed, such harangues became ever louder, and on occasion attracted bewildered crowds.7

His new wife Caroline led a gentle but persistent campaign to reunite her husband with his first-born son, in result of which Charles was eventually admitted to his father’s household. On the rare occasions when Charles later talked about his father it was with respect rather than affection. Charles was nonetheless imbued by George’s religiosity. He recoiled from risqué chat, and if he found himself in the presence of students using swear words or telling dirty jokes, he tried to summon ‘the courage to rise and go’. The young man who went up to Merton College Oxford in October 1877 was reserved, sometimes morose and given to sighs, with a latent expressive side which awaited someone to waken.

On the first anniversary of their meeting Edie wrote: ‘This time last year I saw Charlie first. He thought me prim, severe, frigid and one who would “district visit”. I thought him compact, and rather fast – with a very powerful face that I didn’t understand.’8 First impressions had since been revised. By November Charles had produced a hand-made book of sonnets, each page wreathed in leafy garlands and faced by a pen-and-ink drawing. Next May they became engaged.

Charles was now a medical student at Guy’s Hospital, and marriage was some way off. However, the wedding, when it came, came in a hurry. In August 1885 Minna was home from India; perhaps on impulse it was agreed that the marriage should take place before she returned. Since Minna’s passage was booked in mid-September, this meant a special licence for the ceremony. When the day arrived, Edie was led in on the arm of her father’s brother, Uncle Edward (coiner of ‘EdiePuss’), followed by two bridesmaids, Charles’s half-sister Ethel, and Minna’s nine-year-old daughter Elf. The ceremony was conducted by the vicar and Charles’s father, with whom, interestingly, Edie had formed a good relationship.

It is worth summarising characteristics of the two families that were now connected. Common to both were strong evangelical convictions, commitment to education, forebears in the military and holy orders, and careers spread across the British Empire. The Bible, learning through inquiry, and empire formed the ground on which their children would stand. In the background was recurrent giftedness in mathematics on Edie’s side, and a sense of victimhood on Charles’s.

Back at Woolwich in the autumn, Charles was Assistant Physician Clerk to his tutor, studying for final exams, and Edie was pregnant. In May the next year, just before the birth and the exams, they took a short holiday in Eastbourne. While they were there Edie wrote her only journal entry that year.

Now my Charlie has gone to church, I will just scribble a few lines. This is our second honeymoon, – I think it will be our last … For always after this I hope there will be someone else with us. It does seem strange! To think that next month I expect to have a baby in my arms, that little baby I feel stirring within me as I write. Oh! God, make us wise parents, and bless the little one …9

Looking back three years later, it had not turned out quite like that.

We married rashly, before he was qualified, and thus hampered ourselves. My John, my ever dear John, began to come too soon, and all those months of anxiety and terror, while Charlie worked for his exams, and every month was eating up our money, I carried with me – my John. The walks, the roads of Woolwich must be paved with my prayers, I prayed so much.10

Ripley was the company town of the Butterley Iron and Coal Co Ltd. Edie remembered it as ‘crowning a lonely, windswept hill – you could see it high up against the horizon for miles round – its tall square Church tower, oversized Town Hall, Factory chimney and Waterworks being landmarks that stood out against the cold grey sky.’11 The closest she and Charles had so far come to such places was from the windows of trains, and their first impressions in September 1886 were unnerving. Charles’s southern accent, Oxford education and dislike of profanity did not stand him in good stead with col

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...