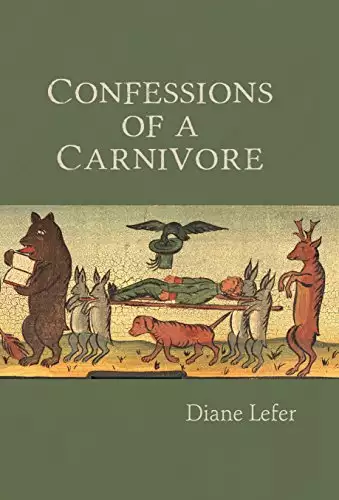

Confessions of a Carnivore

- eBook

- Paperback

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

As the US goes to war and baboons fall deeply, tragically, in love, Rae's involvement with Gorilla Theater--street agitators raising awareness of animal rights--leads inexorably to confrontations over human rights. Especially when Jennie is disappeared. Confessions of a Carnivore is an antic romp through a minefield, a novel about animal behavior, endangered species, endangered democracy, and love.

Release date: April 26, 2015

Publisher: Fomite

Print pages: 330

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Confessions of a Carnivore

Diane Lefer

Chapter One

It was Heaven to be drinking again and for that I could thank Jennie.

It’s not that I ever actually quit, except for the years when I was agonizing over my alcoholic ex, but I had stopped drinking for pleasure. I had forgotten what it was like to be reckless. My conscious mind had repressed the exhilaration of risk but now the memories were back: the blissful irresponsibility, all those moments when I’d given up fighting him for the car keys and had left us in the hands of fate; the intoxication as again and again I surrendered, even though I knew it was wrong, even knowing it might cost my life and the lives of innocent others. And each time, after the struggle? No conscience, no fear. The oceanic thrill of not caring.

I thought that was over for me. I’d seen the cost, even if he hadn’t. Living in LA and not being the world’s best driver even when sober, I didn’t allow myself so much as a taste if there was any chance I might end up behind the wheel which, until I became friends with Jennie, was more or less all the time.

Every time you get in the car, you’re demonstrating your faith in other people. Every time you reach your destination alive, your trust has been repaid. For this reason, I love the freeways. I don’t, however, love to drive them.

Where’s the lane markings? Is that a stripe, or a popped seam filled with tar? Is this one of the ramps where you have to merge at speed or one of those where if you don’t stop though it isn’t marked you’re gonna get killed? Why don’t the stripes and the reflectors coincide? Where are we anyway? The exit signs are draped in black. All I see are billboards for titty clubs. Right lane must exit. Let me over! I don’t want to get off. Or do I? Three left lanes exit west. Which three? Does that include the car pool lane? Use your turn signal, asshole. There’s debris flying off the back of that truck. There’s an axle in the middle of the road. There’s a piece of black plastic that just blew onto my windshield and now it’s caught in the wipers and oh my God I can’t see a fucking thing!

Jennie freed me from all this. Once we started going everywhere together, she preferred to do the driving. I preferred to sit back and revel in trust. Plus it seemed all right to have a thermos of margaritas in the car and for me to be drinking them.

I warned her: “Once we get to the reservation, alcohol is strictly forbidden. If it’s like other reservations I’ve been to, though I’ve never been to Basoba, I don’t really know, but in general, it’s a matter of sovereignty and the tribal police will at the very least confiscate it and maybe even fine or arrest us.”

“Public Law 280. California Indians aren’t allowed to have tribal police or enforce their own laws, if they have any,” Jennie said. “Anyway, how can you have a casino without liquor?”

“I don’t know. Maybe the casino isn’t on reservation land.”

“If it isn’t, the State wouldn’t allow them to have a casino,” Jennie said.

She held out her thermos cup for me to pour her another. Illegal, of course, but according to Jennie, Koreans had been oppressed for so long, they were no longer interested in following rules. According to me, if she was comfortable drinking and driving, well, that wasn’t my business. It was her choice. This kind of deluded thinking reminded me ever so pleasantly of my youth.

It’s sad to have become this stereotype, an older woman with a romantic past. As a useful aside, I should point out that in animal behavior studies, stereotyped behavior, or “stereotypy,” refers to the mechanical repetition of an action or gesture, seemingly beyond conscious control and indicative of psychological stress.

Jennie and I had been carousing ever since she took the bar exam and then decided not to look for work until she got the results in November. The truth is, she hadn’t done much studying for the exam. “If an idiot like Pete Wilson could pass,” she'd said, referring to a particularly unpleasant former governor, “why should I worry?” Being a true friend, I didn’t try to dissuade her from a course that led to all but certain failure. Success would mean being a lawyer which I was sure would lead to all but certain boredom and grief.

“When we get to Basoba,” I said, “don’t ask any direct questions. I mean don’t ask any questions at all. With Indians, it’s impolite. Even if the question is polite. Like right now, if I wanted to say, Do you mind if I roll down the window? what I’d do is say, Well...I’m thinkin’ ‘bout rollin’ down that window, and then I’d wait and see your reaction.”

“Roll down the friggin’ window,” Jennie said. “I don’t care.”

It was amazing to have a friend again and to be drunk.

The sign at the side of the freeway said, Lane closed ahead. Merge left. But as we came around the curve it was the left lane that was closed and there was much honking and screeching of brakes and Jennie’s car was a sure bet to rear end the red sports car in front, but she turned hard to the right, we went up on two wheels, wobbled, then slid onto the shoulder and jerked to a stop as Jennie pulled on the parking brake.

“My God,” she said. “That was close.”

“Someone should sue Caltrans. Putting the sign–”

”It wasn’t them,” Jennie said. “It was me.”

“The sign said Merge left.”

“Didn’t you see what just happened?”

“I saw a sign that said Merge left but–”

“I could’ve really fucked us up,” Jennie said.

“It’s not that big a deal,” I said. “It would just be the continuation of your life with certain changes,” I said, “that’s all. Facing and fighting societal and architectural barriers every day of your life, for sure, but–”

“Jesus,” Jennie said. “Give me the thermos.”

I said, “The prospect doesn’t frighten me.”

I poured margaritas, one for Jennie, one for me, and marveled at our closeness. Like many women–stereotyped again–I’d gone from trying to love the whole world to settling all my affections on a few, then on one, and then, the ultimate older woman cliché–i.e., those who cannot rely on humans turn their affections to animals–I fell in love with Molly, my cat. I’d come to a point in my life when instead of trying to make new friends, I was doing my best to lose the old ones. Jennie had come along and changed that.

In her company, I regretted what I’d lost. With her, I was able to expose myself and be honest: “Jennie, when you talk to your cat, do you just automatically say I love you? I mean does it just flow out of your mouth without the slightest inhibition? Do you call her angel and sweet girl–OK, I know yours is a boy–and darling? I do. But you know I used to actually feel a thrill watching her cat food come down the conveyor belt in the supermarket. The sight of those cans rolling over to the cashier and the scanner would set me aglow because it was food for her, and I could almost hear her purr and feel her head brushing against my hand, I swear I’d get orgasmic right there in the checkout line. I loved leaving the apartment because even on my way out the door I was imagining what it would be like when I got home and she’d come running to greet me. And Jennie, it’s gone,” I said. “I still say I love you I love you I love you but it’s just habit. Do you think that’s what happens after a long marriage when people suddenly realize there’s a total absence of feeling and after years of saying The Words they suddenly turn to each other and say, I never loved you. If that’s–”

“Your cat?” she said. “We’re talking about your cat when we almost got killed!”

“Yes, my cat.”

“I tried to brake and my foot went down and down and down and I felt nothing! No contact. No connection.”

Connection was the point, exactly. Sociologists say we need autonomy, security, and relatedness to be fully human. Sometimes I swear Molly is more human than I am.

“You need to trade this in for a reasonable vehicle,” I said. “God, it’s embarrassing riding around in an SUV!”

“This is not an SUV. It’s a big car.”

“Connection. That’s the whole point, Jennie.”

Jennie said, “I am not ecologically unsound.”

“No? You are such a brat.” What else can you call a vegetarian who loves red Naugahyde, who goes to steak houses to munch on iceberg lettuce and drink whiskey neat?

“And you’re a pest,” she said. “A real pest.” She turned the key in the ignition.

“Jennie,” I said, “are we friends?”

“What? You want permission to say something shitty to me?”

“No. I mean friends who care about each other? Do you think I care about you? I want to. You know I really want to.”

“What is this?”

Oh, God, I was crying. “Do you love your cat? You picked a good one. Castrated males are the most affectionate, don’t you think? My little girl isn’t a lap cat, Jennie. She just isn’t. And drinking and driving is bad. Really really bad. I think you have no idea how bad it is. It’s wrong, Jennie, I know it’s wrong, but I don’t cry anymore, did you know that? Thank God for tequila. Something to make my hard heart melt. Hey, we’ve got to get out of here before the highway patrol stops to help.”

"How can I drive without brakes?"

"The parking brake. Use the parking brake."

She also needed a break in the traffic. She got it when two cars coming around the curve veered to the right lane and collided.

“I hope no one’s hurt,” Jennie said, not waiting to find out.

Out onto the road we ventured again, exited the freeway and, using the parking brake at intersections, made it to a service station. Jennie’s big car up on the lift, we crossed the street, drawn by a poster that said Gorilla Theater, my heart heavy with my own admission.

I’d lost sympathy with myself because I no longer loved my cat. My beautiful and personal representative of the species to which we owe our civilization.

Until they killed and chased away the birds, we couldn’t plant. Until they killed the mice, we couldn’t store our grain. Living in one place, instead of being nomadic, building cities, none of this could have happened without them. And then... even when we didn’t need them anymore, even when they are of absolutely no practical use, we keep them and feed them. It’s no longer symbiotic. They don’t protect our property the way a dog does. They don’t behave like slaves to enhance our shaky self-esteem. We continue to live with cats because they awaken our most noble sentiments. It is only through our relationship with them that we learned altruism, caring about the well being of a creature that does nothing for us and does not perpetuate our gene pool. Cats awakened our inherent but unevolved aesthetic sense. They left us startled and breathless, contemplative with their beauty. They insist we be our best selves. You can beat a dog and you’re still the master and it will still love and obey but mistreat a cat, and she’ll leave. She’ll cooperate with you only if she values you. You cannot control her.

Yet at any moment for any reason I can have Molly put to death. What kind of legitimate relationship can there be between us? Though I didn’t “buy” her, though I “adopted” her, and though she is my “companion,” not my “pet,” in reality–though she is not a thing–by law she is thing-like, my possession. She doesn’t know it. But I do. Is it any wonder I hate the law? What does it do to a human being to have such power over another living thing, all the while using the word “love”?

Still, in spite of my hard heart and ultimate power, I let her guide me, as I expect she is leading me to a more evolved state I cannot, with the limitations of human vision, even imagine.

Weezie Wickham agrees with me.

There, I’ve mentioned Weezie–Louise. You'll meet her later. Now, back in the auto repair shop, any minute now, you’ll meet Marcia. But for the moment, you’re still with me and my guilt.

I was guilty, during these dark days of world crisis, to ignore the state of the union and instead spend hours at the LA Zoo watching the traumatized little markhor. If they’d given her a name, I didn’t know it.

I watched her nibble on browse. She took a few steps to the right, stamped her left hind leg three times in nervous succession, and reached for another leaf. She bent her head back and twisted her neck and I did the same to see if there was anything up in the sky. The big male moved closer to get at some leaves and she tripped daintily to the door and off-exhibit.

“Bambi!” cried a child. “Bambi! Don’t go!”

“That’s not a bambi,” said the mother. “That’s a sheep. Baa baa.”

The markhor is not a fawn or a sheep. She’s a refugee. A mountain goat, a species highly endangered, in greater danger of extinction each day, and this particular markhor was evacuated from a war zone in Afghanistan. Traumatized for sure, but by war, captivity, or by the big ram?

As I watched, she returned and thrust her front legs up against the wall and she stretched her head and twisted her neck. Stereotypy. When she stepped down, the stripe on her back trembled and quivered like a spinal cord made visible. She bent her front knees and lowered herself to the ground. Her tail beat against the planet with flashes of white. I watched her nod her head again and again, then bend her neck backwards till her head touched that spinal stripe.

We research department volunteers watch them to try to know how to make their lives better. What if we watched other people that way, not judging them, only judging how to bring them greater comfort?

And that’s how David hooked me. He was precisely not my type. Just the kind of white guy who thinks the earth and its inhabitants were created for his use, and I knew I’d be a better person than I’d ever been before if I could bring myself to know him and not judge him.

I’m throwing a lot at you all at once. Just relax. There’s no other way when you’re talking about the whole web of creation and all that cosmic blah blah. David never liked the way I tell a story. “The human mind is suited to linear thinking,” he told me. “You have to build a logical chain.” And be shackled in it? And you, do you really want to be like David? Anyway, he's wrong. There's nothing linear about us on a molecular level.

So hang on a bit and I’ll back up and introduce you to David and to Lyle. In the meantime, the markhor raised her legs up on the wall again and again in a mechanical stereotyped way without frenzy or passion or terror, as if resigned both to captivity and to a lifetime of ineffectual attempts to escape it.

But I was about to tell you about Marcia. A distraught partial blonde in tight shorts and ruffled midriff-baring top–her clothing as unsuited to her ungraceful middle age as my demeanor some would argue is to mine–who rushed into the garage soon after Jennie and I returned to find the big car still up on the lift.

“Hello, Marcia,” said the owner from behind the counter.

“Hi, Marcia,” said a mechanic passing by.

“Marcia! Hey!” called the guy who was working on Jennie’s car.

“Do you think she’s fucking all of them?” Jennie asked me.

“Is anyone that hard up?” I said, though her large breasts were very much in evidence and that often counts for a lot.

“You've got to help me!” Marcia said. “I'm in trouble!”

The owner said, “Sure, Marcia, what's wrong?”

“I forgot to go to jury duty and they're fining me $1500. So can you write up an invoice that claims my car broke down so I'll have an excuse?”

“Sure, Marcia," he said. “What date was it?”

“How the hell do I know?”

Then she sat down beside me, put a hand on my knee and said, “I'm an alcoholic. But the good part of it is, I've been certified mentally ill.”

I said, “That sounds like a good enough excuse to get off jury duty.”

“Not in California,” Jennie said.

The mechanic broke us the bad news. “Your brake cylinder went, but that’s not all. It’s the...” many more things there’s no way I’m going to remember. He said, “You’re going to have to leave it overnight.”

“No powwow,” said Jennie.

“Powwow?” Marcia’s eyes were wide.

“We were going to Basoba.”

“Hey-a-hey,” she said, “hey-a-hey. I’m a shamaness though I don’t practice anymore. At my job, they accused me of witchcraft. Me? Witchcraft, me? Of all people, when I’m a survivor of satanic abuse. My grandfather and the Governor of Ohio kidnap Amish children and eat them. You know in traditional societies, among the primary peoples, when someone exhibited signs of what we so ignorantly call schizophrenia or was in some other way different, that person was believed to have the depth of complexity of soul, the open communication to the spirit world, the vision and capacity to be a shaman. So when I was diagnosed as mentally ill, I started shamanic training. But you don’t get the same respect here. If you want to go to Basoba, I’m overdue for a visit. I’ll drive you.”

“Wow! Great! Thanks!” said Jennie.

And I remembered why I’d stopped hanging out with drinkers. The bad judgment thing.

Jennie passed the thermos to Marcia.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...