One

David Rush was an Eagle Scout.

Was.

In addition to his scout training, he had secured an ROTC scholarship for his first two years at Missouri State and frequently spent weekends camping with his uncle, Lt. John Rush, a retired medical officer in the United States Marine Corps.

If there was anyone in Paul Tillerson’s B-field that fateful night who possessed the know-how to survive the carnage—possibly even lead the other victims out of danger—it was David.

David Rush had the skills to survive.

And his attackers knew that.

Which is why he was one of the first targets of the ambush.

What follows in this documentary is not conjecture. These are facts, confirmed and verified by a panel of independent researchers and forensic specialists.

“Is this going to be gory? I can’t deal with gore. Especially eye stuff. And finger—”

“Shhhh.”

—first crossbow bolt to enter David Rush’s body entered below his knee, severing tendons and chipping bone. The pain must have been excruciating.

“Ew.”

“Shut up!”

—vestigators unanimously agree that the second bolt entered David’s rib cage while he was lying on his stomach, already prone. Despite being fired at close range, this second shot missed all of David’s vital organs. Which means that he would have been able to survive both of these injuries if he had received light triage and been taken to a hospital.

But there was no hospital. An hour after he had been shot, the injured David Rush was finished off by the group’s ringleader with a single, smooth cut across his jugular vein.

“Where is this going?”

“No, I’m serious, be quiet. You got me to watch this thing. Now let me watch it. She’s my roommate and I want to—”

“Okay.”

—as widely reported by the mainstream media, the perpetrators of the Kettle Springs Massacre were each dressed as Frendo the Clown, a character used to promote Baypen corn syrup and the town’s unofficial mascot.

But, as the next hour will show, this is one of the very few accurate details circulated by the media in the days and weeks after the crimes. What follows will—

“My bullshit sense is tingling. Where did you find this, Pete?”

“My uncle.”

“By any chance an uncle who thinks the president is a lizard person?”

“I’m kicking you both out soon. I can’t hear.”

“Sorry.”

—nica Queen. Matthew Trent. David Rush. It will sound shocking. Maybe even offensive to some viewers, but the truth is that there were only three teenage victims of the Kettle Springs Massacre. Not twenty-six as reported. And the killers were not Sheriff Dunne and the townsfolk. Nor was the mastermind Arthur Hill, the town’s main jobs creator. No—the killers were the students of Kettle Springs themselves.

The police, the FBI, the media corporations that control our television and internet and want to keep us in a perpetual state of fear, all were complicit in this cover-up. All furthered the false narrative of twenty-six helpless school-age casualties. Why? Why would they undertake such an elaborate false flag operation? Why lie to the American people? And who were the real victims, lured to first the field and then the Baypen refinery that night?

“Okay. True. This does seem far-fetched, but hear it out.”

“SHHHH!”

—to understand why, we have to take a closer look at the real sociopath at the heart of this story. The first person in Kettle Springs to don a Frendo the Clown mask in anger. The organizer of the entire plan. The girl who leveraged the pain of a divided small town, a divided nation, and has gone on to make that schism even worse.

The girl who dragged a hunting knife across David Rush’s throat while he lay begging for help.

The girl who hatched the plan to kill and frame the town’s authority figures.

A girl who, before the murders, if you were to believe everything you hear on the news, had been living in Missouri for less than a week at the time of the attack. None other than—

“Quinn Maybrook.”

“See! Told you. She’s been lying!”

“Oh please. That isn’t real footage. I recognize the costume. It’s from that Lifetime movie they made.”

“Keep watching. It’s not about the footage, which, yeah, is a little janky. They have facts. I was skeptical, too, at first, but—”

“Shh. Do you hear that?”

“Oh fuck, hide it, hide it.”

Quinn Maybrook stood in the doorway and saw her face on the laptop screen before Mason could fumble the computer closed.

Then she shrugged.

It wasn’t worth getting mad about anymore. She couldn’t get away from this shit. No matter where she went. Not even after a long day of classes, not even in her own dorm room.

Figured.

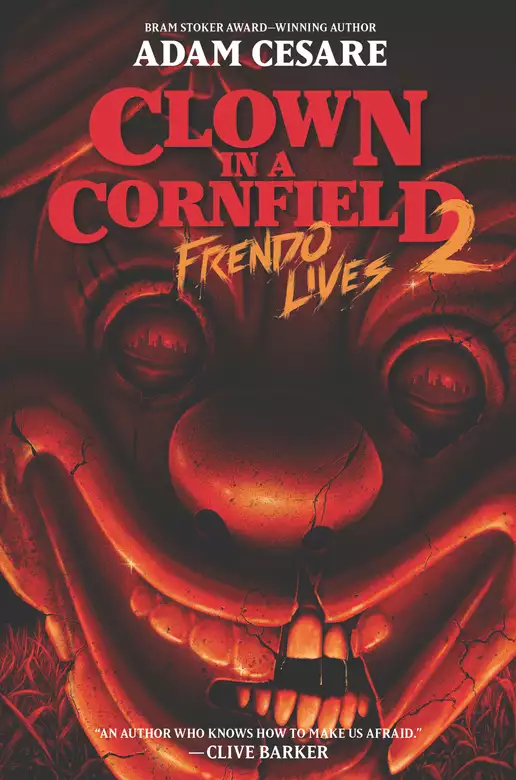

She was familiar with the specific video they were watching. It was the most popular one for some reason. The “documentary” was titled The Baypen Hoax, and even though Quinn, Cole, and Rust had successfully petitioned to have the original video removed from Facebook, the same “documentary” was re-uploaded to YouTube multiple times a day, the takedown notices unable to keep up. The facts in the video were all wrong, of course. And the conclusion that Quinn, Cole, and Rust had committed mass murder and then framed their victims—Sheriff Dunne, Arthur Hill, and the rest of the town’s adults—was as laughable as it was convoluted. There were even sequences where Quinn’s face had been deepfaked (poorly) onto the actress who played Ronnie Queen in one of the made-for-TV movies. Bad as the effect was, the image seemed to stick with an audience eager to see what Quinn would look like wearing a Frendo the Clown costume herself.

Never discount the gullibility of people on the internet, though. Janky production values and all, there were people who believed. Or at least wanted to believe, needed that outrage in their lives like a handrail.

Quinn had thought Dev was smarter than that.

“If you’re going to watch conspiracy theory videos about me, there are better ones. More fun ones,” Quinn said. She didn’t know why she was engaging with this right now. “There’s one where I’m secretly Cole’s half sister and we framed Arthur Hill to split his fortune. That’s a good one. And one where I was trained by the Zodiac Killer at a defunct summer camp in Virginia. Also good.”

Sitting on the carpet, Dev swallowed a big gulp of air. Guilt stuck in her throat.

Quinn didn’t wait to hear what excuse her roommate was going to stammer out. She hitched up her computer bag, leaned into the dorm room, and plucked the pillow off her bed.

“Oh, and FYI,” she said, “David Rush wasn’t even a real person. But Rust Vance really is an Eagle Scout, so that’s probably where they got that tidbit from.”

Dev started to get up from the floor, where Pete and Mason, two boys from down the hall, were sitting cross-legged and staring at the carpet.

Good. Let them squirm.

“Quinn—I’m sorry, we were just . . . ,” Dev started.

“I guess I’ll go sleep in the study lounge tonight,” Quinn said, and slammed the door in Dev’s face as she approached.

Quinn had only made it a couple of feet down the hall when she heard their door open again. She forced herself not to look back.

“I’m sorry!” Dev yelled. “I’m really sorry!” Her apology was loud enough that she must have embarrassed herself, because their door squeaked closed just as quickly as it was opened.

Quinn and Dev had only known each other for a few weeks. They hadn’t talked much in that time, despite sleeping in twin beds five feet apart, facing each other. Every night was like an awkward sleepover. Even so, most of their conversations had been Dev apologizing to Quinn. Sorry, but I mixed up our shower caddies and used your shampoo. Sorry, but did you take Econ notes? Sorry if I’m loud on the phone, but it’s still early where my parents are.

And there were more apologies. Dev was sorry about the smell of her microwaved breakfast burritos. And also sorry that the RA had found the contraband microwave she kept in their shared closet.

Even with all these annoyances, Quinn didn’t dislike the girl. She didn’t think much about Dev at all, outside of pitying her for the hard time she seemed to be having adjusting to city life; the long hours she spent on the phone with her parents; and the trunk of arts and crafts materials, markers, and bracelet looms that she kept under her bed. But now the thought of Dev gossiping with those boys, speculating about Quinn’s complicity in a mass murder . . .

Quinn was angry. So angry it’d be hard to sleep.

In the hallway, a few faces prairie-dogged out of their rooms to see what was up, who was doing all this yelling and stomping. It was a long walk. Quinn and Dev were the last door at the end of the hallway. The lookie-loos caught a glimpse of Quinn marching to the elevator before they each disappeared back inside.

Oh. Her. The Clown Girl. Figures.

It wasn’t that everyone in the country believed the lunatic theories they saw online. No, those were fringe ideas with tiny fringe audiences. Most of America knew what really happened in Kettle Springs. Or knew a close-enough-to-the-ballpark version of the truth, which varied depending on the documentaries they’d seen, the podcasts they listened to, or which cable news station was on at their parents’ house. But a few rejected that truth, thought Quinn was a criminal mastermind who’d roped two small-town gay lovers into a heavily armed assault against traditional American values.

It was only a few weeks after the attack that the conspiracy theories and abuse started. And as a result, Quinn had spent most of the last year with her social media deactivated to try to step away from the toxic stew of lies online and stem the constant—and sometimes quite detailed—death threats. She didn’t have Instagram or TikTok on her phone, but still she never went anywhere without the device. It connected her to the people she loved. It could connect her to help.

Before leaving for college, she’d sat with her dad at the kitchen table and they’d performed timed drills to see how quickly she could set the phone to emergency mode. Then they’d tested which was faster, emergency mode or dialing 911 the traditional way. If she needed, Quinn could reach the Philly police without even looking down at her phone screen.

The dorm elevator smelled like chicken fingers, and Quinn could see why. Someone had let half a nugget slip from their late-night snack, probably while trying to hit a button for their floor, judging from the streaks of ketchup.

Quinn pressed M for Mezzanine. This building used to be a hotel, before the university bought it and converted it, quickly and cheaply, into freshman and sophomore suites. During that construction, they’d also portioned up the ballrooms of the second floor into residence life offices and study lounges.

The elevator car shuddered, and Quinn stared at the oily splotch of ketchup.

For the rest of the students in this building, college life was all fun and parties. With a little bit of learning thrown in. Maybe college wasn’t the total freedom they’d imagined, but it was much more freedom than they’d ever had at home. Quinn’s classmates had a bustling city at their front door. They knew about that one corner store that didn’t card. There was a small dining hall in the building’s basement that served fried food any time you were hungry, even at—Quinn checked her phone—nearly midnight.

Quinn wished she felt the same way. Was able to feel the same way.

She wanted to enjoy the curly fries. A little over a year ago, after pulling into Kettle Springs for the first time, coming back to Philly for school had been the plan. The dream.

This, being here, being back in the city she called home, was what she’d wanted. She’d wanted to be far from Missouri, live right on Broad Street, a few blocks’ walk from City Hall and the heart of Philadelphia. But now that she’d seen death—now that she’d killed to survive—Quinn just couldn’t get as excited about an eight a.m. Intro to Lit class, or how much detergent was enough in the dorm’s strange washing machines, or complaining that her roommate was taking so long in the shower. The alienness of college, its freedoms, all seemed like inconveniences at best, dangers at worst.

DING!

The elevator doors opened onto darkness.

The building’s second floor was often like this when Quinn came down late at night, looking for a little peace, but the darkness was still sometimes unnerving.

Quinn readjusted her pillow under one arm and waved a hand over her head.

There was a mechanical click somewhere, a circuit switched on, and cool bright fluorescent lights lit the hallway.

The lights were on a motion sensor. The darkness was good, actually, Quinn told herself. It meant she was alone down here.

Quinn walked forward into the hall, her phone buzzing with a text. She looked down.

Oh. Surprise, surprise. Dev was sorry.

Quinn opened Messages and silenced the conversation. She did not silence her phone. She never silenced her phone, even while she slept. There was always a chance that her dad or Cole or Rust could call with an emergency.

It was quiet down here, abandoned on this floor that the school hadn’t bothered to remodel from when it was a hotel. Even with the sound-dampening qualities of the carpet and the popcorn ceilings that must’ve dated back to the ’70s, Quinn’s footsteps seemed to echo. The university offered cleaner, more modern places for students to study at night, but this one was closest, and a place where Quinn Maybrook could be alone. Maybe the only location on campus without classmates whispering into their hands, a barista asking her for her autograph on the back of a receipt, or a group in the dining hall trying to “accidentally” catch her in the background of a selfie.

At the end of this hall there was a large, open room with circular tables, booths, and a small kitchenette to make coffee or tea, but Quinn wasn’t headed that way. Instead, she turned on her phone’s flashlight and directed it into the slim, rectangular windows of the doors on either side of her.

These were private study rooms. They were empty now, but during midterms and finals were so in demand that they had to be reserved ahead of time.

She peered into a few windows before settling on a room with three chairs and stepping inside.

“Shit.”

A blanket.

She’d left her room in such a hurry, she hadn’t grabbed a blanket. It was fine. At least she had her bag, which meant she had her laptop, her phone charger, and the small collapsible combat baton she kept for self-defense.

Quinn rarely arrived back at the dorm after dark, but on Thursdays it was unavoidable. Her only elective was a film class that consisted of an hour of lecture on Friday mornings and a two-hour screening block the night before. Tonight’s film had been Man of a Thousand Faces. Rust would have liked it. It was an old black-and-white movie starring an old black-and-white movie star that was about an even older black-and-white movie star. She’d been enjoying it well enough until there was a scene where the actor was in clown makeup. Then she had a hard time focusing on anything but the faces in the screening room around her. How some of her classmates were watching for her reaction.

Quinn placed her laptop on the desk and opened it, not to use the computer but just to make it look plausible if anyone peeked in that she could be studying. She then pushed the three chairs together in a line to make a kind of bed.

She put her pillow against her back and stretched her feet out, trying to get cozy.

In the hallway, through the long rectangular window, she watched as the overhead lights clicked off, one by one. She liked that. Liked that the timer attached to the motion sensor was pretty short. It let her know there was nobody else on this floor with her. This dorm, of all the housing on campus that allowed freshmen, was the only one with a single entrance. This entrance was guarded overnight, and every guest, even if they were students, had to sign in and leave their IDs kept in a flex-folder behind the desk for the length of their stay.

In the dark, feeling safe, Quinn scrolled her phone and hoped she’d soon get sleepy.

Apple News was all depressing stories. But at least she wasn’t featured in any of them. Two months ago, there’d been an entire week where she hadn’t shown up in any Google Alerts. Which was nice, but it was the calm before the storm. Two weeks and a few days ago had been the one-year anniversary of the Kettle Springs Massacre, and the retrospective think pieces had been out of hand. And the coverage was still ongoing.

She left the News app and went to Messages.

The top message, most recent, was Dev.

Quinn left the girl muted and unread.

Under Dev was her father, not in her phone as “Glenn Maybrook” but as “Dad.” His last message—was it this morning or had he sent it before she went into the screening room for the movie?—was a simple Love you.

Under Glenn Maybrook was a group chat she’d labeled “The Boys.”

That was Cole and Rust.

Then there was an automatic message from the last time she’d ordered takeout. And under that, inactive for days, was a three-person group text labeled “The Girls.” Tessa and Jace. Were her best friends from high school still “The Girls” if she had only seen them once since moving back to Philly? Nothing had gone wrong, not outwardly at least, the last time they’d been together. Tessa was even living here, on campus, a five-minute walk from Quinn. But there was something about the way they both looked at her. Like they had questions they weren’t sure they were allowed to ask. Like Quinn was someone famous that they used to know. Or maybe that was too self-serving. Maybe Tessa and Jace looked at Quinn like a curiosity. The damaged girl they used to know.

She didn’t want to think about that right now, wonder if she still had two of her closest friends, so instead she opened up the text with the boys and tried to focus on something that made her happy. Something she’d been looking forward to.

Where are you now?

She waited a few seconds; then when neither of them replied, she buzzed their phones with an emoji. If they were trying to sleep? Then tough. She wanted to know how close they were.

CH: Motel outside Pittsburgh.

She smiled, then responded.

Motel? You’re in my state! Can’t you just drive it in shifts? You’d get here tonight.

CH: It’s a very long state. If you didn’t know.

Ha. I know. You two be safe in Pennsultucky. Try not to be an asshole.

RV: What’s that?

Oh he can text.

RV: I do if I’m not allowed to sleep.

Quinn started to type them out an explanation of Pennsultucky, but halfway through looked up, the smile on her face wilting.

She’d been so absorbed in the conversation, so looking forward to her friends coming in for a visit tomorrow as part of their road-trip week away from Kettle Springs, that she hadn’t even noticed that the hallway lights had switched back on.

There was somebody out there.

Was it Dev? Had she come down to apologize in person since her texts had gone unanswered?

Had Quinn been so wrapped up in texting Cole and Rust that she hadn’t heard the elevator ding?

She didn’t stand from her makeshift bed, but did stare at the skinny privacy window that faced into the hall.

There. Softened by the carpet, but still distinct, she could hear footsteps.

Footsteps and something else. Between the steps there was a kind of dragging sound. Something rubbing against the wall.

The sound came closer. And Quinn, her legs still propped up on the bed she’d made, moved her hands to her computer bag.

A shadow fell over the wall opposite the window; then whoever was casting the shadow stopped. They were trying not to be seen.

She unzipped the top compartment on her bag and reached inside.

The combat baton was not legal to own in Pennsylvania. Or most of the states that bordered PA. But for thirty dollars, shipping included, she’d had a couple of them delivered to her Missouri address no problem. Rust had suggested the baton. It was light, easy to carry . . . discreet enough for college.

Quinn gripped the handle of the baton, but didn’t take it out of the bag. If she needed to take it out, she would also need an extra second to flick her wrist and extend the steel bar, tipped with a textured steel knob, to its full length.

“Dev?”

A face appeared in the window. It was certainly not Dev.

It wasn’t a fellow student, either.

“Knock knock?” the man at the window said, and smiled.

As he stepped forward, filling the sliver of window, she could see he was wearing maroon coveralls.

Quinn’s hand unclenched. Her heart rate slowed. Those coveralls meant he worked in the building. That he was one of the maintenance crew.

Quinn nodded and the man opened the door a crack, just wide enough for his face.

The man had a couple days’ worth of salt-and-pepper scruff, a wrinkled neck, and a bad tooth that she could only see because he was smiling so wide.

“You aren’t sleeping down here, are youse?”

Youse. She’d missed that.

“No. I’m studying.”

Was there a rule against sleeping in one of these rooms? She didn’t think so. She’d done it before. But she didn’t feel like debating that fact if there was.

“Where’s your books, then?”

Where’s your cleaning supplies? And let me see what you’re dragging behind you. But she didn’t say that. Instead she said:

“Do you know how expensive course textbooks are?” She pointed to her laptop and added: “PDFs.”

“Well, I’m going to be running my vacuum, so I’m sorry if it disturbs you.”

She nodded. “No problem.”

He started to let the door close.

A vacuum. He’s a maintenance man with a South Philly accent who’s wheeling a vacuum behind him. And you’re ready to bash his head in with a two-pound steel baton. Dad’s right—therapy should be more than once a week.

She felt silly. Then angry that she felt so silly.

As tired as she was—and she was tired all the time—anger was the one thing Quinn never seemed to run out of energy for.

“Hey,” the maintenance man said, stopping the door before it could close. “You’re her, aren’t you?”

Quinn slowly put her hand back into her bag and wrapped her fingers around the baton.

“Yes. I’m her.”

His expression changed. His mouth was a line. She could no longer see the bad tooth. What kind of videos would they find, in this guy’s search history? Was he more of a Baypen Hoax or an Antipatriot Agenda kind of guy?

He seemed to carefully think about what he was about to say next, then started:

“I want you to know, I—”

DING!

He stopped what he was saying, snapped out of whatever starstruck or indignant path he was about to take their conversation down, and looked to his left to watch the stretch of hallway that led to the elevator.

Over the last year, Quinn had been part of so many interactions that started with “I want you to know . . .” Sometimes they ended with “. . . how sorry I am for all that happened to you.”

And sometimes they didn’t. Sometimes it was something cryptic like “I know what you did.”

A few moments later, Dev was in the doorway, holding the blanket from Quinn’s bed folded in front of her. ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved