- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

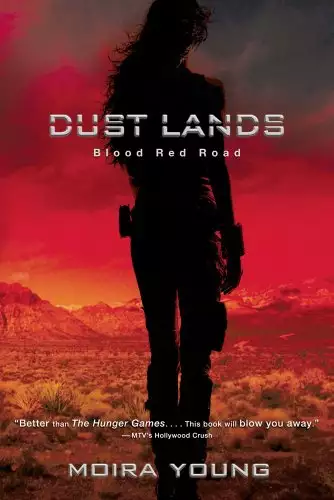

A shining new talent in young adult literature, author Moira Young explodes on the scene with this riveting tale set in a dystopian future. Blood Red Road follows Saba, an 18-year-old who knows nothing but the barren landscape of Silverlake where she lives with her family. Then four mysterious horsemen arrive at her home, kidnap her twin brother, and murder her father. To get her brother back, Saba must leave Silverlake in search of the horsemen. But her journey takes her to strange lands where corruption and violence run rampant.

Release date: January 3, 2012

Publisher: Margaret K. McElderry Books

Print pages: 464

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Blood Red Road

Moira Young

SILVERLAKE

THE DAY’S HOT. SO HOT AN SO DRY THAT ALL I CAN TASTE IN my mouth is dust. The kinda white heat day when you can hear th’earth crack.

We ain’t had a drop of rain fer near six months now. Even the spring that feeds the lake’s startin to run dry. You gotta walk some ways out now to fill a bucket. Pretty soon, there won’t be no point in callin it by its name.

Silverlake.

Every day Pa tries another one of his charms or spells. An every day, big bellied rainclouds gather on the horizon. Our hearts beat faster an our hopes rise as they creep our way. But, well before they reach us, they break apart, thin out an disappear. Every time.

Pa never says naught. He jest stares at the sky, the clear cruel sky. Then he gathers up the stones or twigs or whatever he’s set out on the ground this time, an puts ’em away fer tomorrow.

Today, he shoves his hat back. Tips his head up an studies the sky fer a long while.

I do believe I’ll try a circle, he says. Yuh, I reckon a circle might be jest the thing.

Lugh’s bin sayin it fer a while now. Pa’s gittin worse. With every dry day that passes, a little bit more of Pa seems to . . . I guess disappear’s the best word fer it.

Once we could count on pullin a fish from the lake an a beast from our traps. Fer everythin else, we planted some, foraged some, an, all in all, we made out okay. But fer the last year, whatever we do, however hard we try, it jest ain’t enough. Not without rain. We bin watchin the land die, bit by bit.

An it’s the same with Pa. Day by day, what’s best in him withers away. Mind you, he ain’t bin right fer a long time. Not since Ma died. But what Lugh says is true. Jest like the land, Pa’s gittin worse an his eyes look more’n more to the sky instead of what’s here in front of him.

I don’t think he even sees us no more. Not really.

Emmi runs wild these days, with filthy hair an a runny nose. If it warn’t fer Lugh, I don’t think she’d ever wash at all.

Before Emmi was born, when Ma was still alive an everythin was happy, Pa was different. Ma could always make him laugh. He’d chase me an Lugh around, or throw us up over his head till we shrieked fer him to stop. An he’d warn us about the wickedness of the world beyond Silverlake. Back then, I didn’t think there could be anybody ever lived who was taller or stronger or smarter’n our pa.

I watch him outta the corner of my eye while me an Lugh git on with repairs to the shanty roof. The walls is sturdy enough, bein that they’re made from tires all piled one on top of th’other. But the wicked hotwinds that whip across the lake sneak their way into the smallest chink an lift whole parts of the roof at once. We’re always havin to mend the damn thing.

So, after last night’s hotwind, me an Lugh was down at the landfill at first light scavengin. We dug around a part of it we ain’t never tried before an damn if we didn’t manage to score ourselves some primo Wrecker junk. A nice big sheet of metal, not too rusted, an a cookin pot that’s still got its handle.

Lugh works on the roof while I do what I always do, which is clamber up an down the ladder an hand him what he needs.

Nero does what he always does, which is perch on my shoulder an caw real loud, right in my ear, to tell me what he’s thinkin. He’s always got a opinion does Nero, an he’s real smart too. I figger if only we could unnerstand crow talk, we’d find he was tellin us a thing or two about the best way to fix a roof.

He’ll of thought about it, you can bet on that. He’s watched us fix it fer five year now. Ever since I found him fell outta the nest an his ma nowhere to be seen. Pa warn’t too happy to see me bring a crow babby home. He told me some folk consider crows bring death, but I was set on rearin him by hand an once I set my mind on somethin I stick with it.

An then there’s Emmi. She’s doin what she always does, which is pester me an Lugh. She dogs my heels as I go from the ladder to the junk pile an back.

I wanna help, she says.

Hold the ladder then, I says.

No! I mean really help! All you ever let me do is hold the ladder!

Well, I says, maybe that’s all yer fit fer. You ever think of that?

She folds her arms across her skinny little chest an scowls at me. Yer mean, she says.

So you keep tellin me, I says.

I start up the ladder, a piece of rusty metal in my hand, but I ain’t gone more’n three rungs before she takes hold an starts shakin it. I grab on to stop myself from fallin. Nero squawks an flaps off in a flurry of feathers. I glare down at Em.

Cut that out! I says. What’re you tryin to do, break my neck?

Lugh’s head pops over the side of the roof. All right, Em, he says, that’s enough. Go help Pa.

Right away, she lets go. Emmi always does what Lugh tells her.

But I wanna help you, she says with her sulky face.

We don’t need yer help, I says. We’re doin jest fine without you.

Yer the meanest sister that ever lived! I hate you, Saba!

Good! Cuz I hate you too!

That’s enough! says Lugh. Both of yuz!

Emmi sticks her tongue out at me an stomps off. I shin up the ladder onto the roof, crawl along an hand him the metal sheet.

I swear I’m gonna kill her one of these days, I says.

She’s only nine, Saba, says Lugh. You might try bein nice to her fer a change.

I grunt an hunker down nearby. Up here on the roof, I can see everythin. Emmi ridin around on her rickety two-wheeler that Lugh found in the landfill. Pa at his spell circle.

It ain’t nuthin more’n a bit of ground that he leveled off by stompin it down with his boots. We ain’t permitted nowhere near it, not without his say so. He’s always fussin around, sweepin clear any twigs or sand that blow onto it. He ain’t set out none of the sticks fer his rain circle on the ground yet. I watch as he lays down the broom. Then he takes three steps to the right an three steps to the left. Then he does it agin. An agin.

You seen what Pa’s up to? I says to Lugh.

He don’t raise his head. Jest starts hammerin away at the sheet to straighten it.

I seen, he says. He did it yesterday too. An the day before.

What’s all that about? I says. Goin right, then left, over an over.

How should I know? he says. His lips is pressed together in a tight line. He’s got that look on his face agin. The blank look he gits when Pa says somethin or asks him to do somethin. I see it on him more an more these days.

Lugh! Pa lifts his head, shadin his eyes. I could use yer help here, son!

Foolish old man, Lugh mutters. He gives the metal sheet a extra hard whack with the hammer.

Don’t say that, I says. Pa knows what he’s doin. He’s a star reader.

Lugh looks at me. Shakes his head, like he cain’t believe I jest said what I did.

Ain’t you figgered it out yet? It’s all in his head. Made up. There ain’t nuthin written in the stars. There ain’t no great plan. The world goes on. Our lives jest go on an on in this gawdfersaken place. An that’s it. Till the day we die. I tell you what, Saba, I’ve took about all I can take.

I stare at him.

Lugh! Pa yells.

I’m busy! Lugh yells back.

Right now, son!

Lugh swears unner his breath. He throws the hammer down, pushes past me an pratikally runs down the ladder. He rushes over to Pa. He snatches the sticks from him an throws ’em to the ground. They scatter all over.

There! Lugh shouts. There you go! That should help! That should make the gawdam rain come! He kicks Pa’s new-swept spell circle till the dust flies. He pokes his finger hard into Pa’s chest. Wake up, old man! Yer livin in a dream! The rain ain’t never gonna come! This hellhole is dyin an we’re gonna die too if we stay here. Well, guess what? I ain’t doin it no more! I’m outta here!

I knew this would come, says Pa. The stars told me you was unhappy, son. He reaches out an puts a hand on Lugh’s arm. Lugh flings it off so fierce it makes Pa stagger backwards.

Yer crazy, you know that? Lugh shouts it right in his face. The stars told you! Why don’t you jest try listenin to what I say fer once?

He runs off. I hurry down the ladder. Pa’s starin at the ground, his shoulders slumped.

I don’t unnerstand, he says. I see the rain comin. . . . I read it in the stars but . . . it don’t come. Why don’t it come?

It’s okay, Pa, says Emmi. I’ll help you. I’ll put ’em where you want. She scrabbles about on her knees, collectin all the sticks. She looks at him with a anxious smile.

Lugh didn’t mean it Pa, she says. I know he didn’t.

I go right on past ’em.

I know where Lugh’s headed.

† † †

I find him at Ma’s rock garden.

He sits on the ground, in the middle of the swirlin patterns, the squares an circles an little paths made from all different stones, each their own shade an size. Every last tiny pebble set out by Ma with her own hands. She wouldn’t allow that anybody should help her.

She carefully laid the last stone in place. Sat back on her heels an smiled at me, rubbin at her big babby-swolled belly. Her long golden hair in a braid over one shoulder.

There! You see, Saba? There can be beauty anywhere. Even here. An if it ain’t there, you can make it yerself.

The day after that, she birthed Emmi. A month too early. Ma bled fer two days, then she died. We built her funeral pyre high an sent her spirit back to the stars. Once we’d scattered her ash to the winds, all we was left with was Em.

A ugly little red scrap with a heartbeat like a whisper. More like a newborn mouse than a person. By rights, she shouldn’t of lasted longer’n a day or two. But somehow she hung on an she’s still here. Small fer her age though, an scrawny.

Fer a long time, I couldn’t stand even lookin at her. When Lugh says I shouldn’t be so hard on her, I says that if it warn’t fer Emmi, Ma ’ud still be alive. He ain’t got no answer to that cuz he knows it’s true, but he always shakes his head an says somethin like, It’s time you got over it, Saba, an that kinda thing.

I put up with Emmi these days, but that’s about as far as it goes.

Now I set myself down on the hard-packed earth so’s my back leans against Lugh’s. I like it when we sit like this. I can feel his voice rumble inside my body when he talks. It must of bin like this when the two of us was inside Ma’s belly together. Esseptin that neether of us could talk then, of course.

We sit there fer a bit, silent. Then, We should of left here a long time ago, he says. There’s gotta be better places’n this. Pa should of took us away.

You ain’t really leavin, I says.

Ain’t I? There ain’t no reason to stay. I cain’t jest sit around waitin to die.

Where would you go?

It don’t matter. Anywhere, so long as it ain’t Silverlake.

But you cain’t. It’s too dangerous.

We only got Pa’s word fer that. You do know that you an me ain’t ever bin more’n one day’s walk in any direction our whole lives. We never see nobody essept ourselves.

That ain’t true, I says. What about that crazy medicine woman on her camel last year? An . . . we see Potbelly Pete. He’s always got a story or two about where he’s bin an who he’s seen.

I ain’t talkin about some shyster pedlar man stoppin by every couple of months, he says. By the way, I’m still sore about them britches he tried to unload on me last time.

They was hummin all right, I says. Like a skunk wore ’em last. Hey wait, you fergot Procter.

Our only neighbor’s four leagues north of here. He’s a lone man, name of Procter John. He set up homestead jest around the time Lugh an me got born. He drops by once a month or so. Not that he ever stops proper, mind. He don’t git down offa his horse, Hob, but jest pulls up by the hut. Then he says the same thing, every time.

G’day, Willem. How’s the young ’uns? All right?

They’re fine, Procter, says Pa. You?

Well enough to last a bit longer.

Then he tips his hat an goes off an we don’t see him fer another month. Pa don’t like him. He never says so, but you can tell. You’d think he’d be glad of somebody to talk to besides us, but he never invites Procter to stay an take a dram.

Lugh says it’s on account of the chaal. We only know that’s what it’s called because one time I asked Pa what it is that Procter’s always chewin an Pa’s face went all tight an it was like he didn’t wanna tell us. But then he said it’s called chaal an it’s poison to the mind an soul, an if anybody ever offers us any we’re to say no. But since we never see nobody, such a offer don’t seem too likely.

Now Lugh shakes his head. You cain’t count Procter John, he says. Nero’s got more conversation than him. I swear, Saba, if I stay here, I’ll eether go crazy or I’ll end up killin Pa. I gotta go.

I scramble around, kneel in front of him.

I’m comin with you, I says.

Of course, he says. An we’ll take Emmi with us.

I don’t think Pa ’ud let us, I says. An she wouldn’t wanna go anyways. She’d rather stay with him.

You mean you’d rather she stayed, he says. We gotta take her with us, Saba. We cain’t leave her behind.

What about . . . maybe if you was to talk to Pa, he might see sense, I says. Then we could all go to a new place together.

He won’t, Lugh says. He cain’t leave Ma.

Whaddya mean? I says. Ma’s dead.

Lugh says, What I mean is . . . him an Ma made this place together an, in his mind, she’s still here. He cain’t leave her memory, that’s what I’m sayin.

But we’re the ones still alive, I says. You an me.

An Emmi, he says. I know that. But you see how he is. It’s like we don’t exist. He don’t give two hoots fer us.

Lugh thinks fer a moment. Then he says, Love makes you weak. Carin fer somebody that much means you cain’t think straight. Look at Pa. Who’d wanna end up like him? I ain’t never gonna love nobody. It’s better that way.

I don’t say naught. Jest trace circles in the dirt with my finger.

My gut twists. Like a mean hand reached right inside me an grabbed it.

Then I says, What about me?

Yer my sister, he says. It ain’t the same.

But what if I died? You’d miss me, wouldn’t you?

Huh, he says. Fat chance of you dyin an leavin me in peace. Always followin me everywhere, drivin me nuts. Since the day we was born.

It ain’t my fault yer the tallest thing around, I says. You make a good sunshade.

Hey! He pushes me onto my back.

I push him with my foot. Hey yerself! I prop myself up on my elbows. Well, I says, would you?

What?

Miss me.

Don’t be stupid, he says.

I kneel in front of him. He looks at me. Lugh’s got eyes as blue as the summer sky. Blue as the clearest water. Ma used to say his eyes was so blue, it made her want to sail away on ’em.

I’d miss you, I says. If you died, I’d miss you so much I’d wanna kill myself.

Don’t talk foolish, Saba.

Promise me you won’t, I says.

Won’t what?

Die.

Everybody’s gotta die one day, he says.

I reach out an touch his birthmoon tattoo. High on his right cheekbone, jest like mine, it shows how the moon looked in the sky the night we was born. It was a full moon that midwinter. That’s a rare thing. But twins born unner a full moon at the turnin of the year, that’s even rarer. Pa did the tattoos hisself, to mark us out as special.

We was eighteen year our last birthday. That must be four month ago, near enough.

When we die, I says, d’you think we’ll end up stars together, side by side?

You gotta stop thinkin like that, he says. I told you, that’s jest Pa’s nonsense.

Go on then, if you know so much, tell me what happens when you die.

I dunno. He sighs an flops back on the ground, squintin at the sky. You jest . . . stop. Yer heart don’t beat no more, you don’t breathe an then yer jest . . . gone.

An that’s it, I says.

Yeah.

Well that’s stupid, I says. I mean, we spend our lives doin all this . . . sleepin an eatin an fixin roofs an then it all jest . . . ends. Hardly seems worth the trouble.

Well, that’s the way it is, he says.

You . . . hey Lugh, you wouldn’t ever leave without me, would you?

Of course not, he says. But even if I did, you’d only follow me.

I will follow you . . . everywhere you go! When I say it, I make crazy eyes an a crazy face because it creeps him out when I do that. To the bottom of the lake, I says, . . . to the ends of the earth . . . to the moon . . . to the stars. . . !

Shut up! He leaps to his feet. Bet you don’t follow me to skip rocks, he says an runs off.

Hey! I yell. Wait fer me!

† † †

We run a fair ways out onto the dry lakebed before we find water enough to skip stones. We pass the skiff that Pa helped me an Lugh build when we was little kids. Now it lies high an dry where the shoreline used to be.

We walk till we’re outta sight of the shanty, outta sight of Pa an Emmi. The fierce noonday sun beats down an I wrap my sheema around my head so’s I don’t fry too much. I wish I took after Ma, like Lugh, but I favor Pa. It’s strange, but even with our dark hair, our skin burns if we don’t cover up.

Lugh never wears a sheema. Says they make him feel trapped an anyways the sun don’t bother him none. Not like me. When I tell him it’ll deserve him right if he drops dead from sunstroke one day, he says, well if that happens you can say I told you so. I will, too.

I find a pretty good stone right off. I rub my fingers over its flat smoothness. Feel its weight.

I got a lucky one here, I says.

Lugh hunts around to find one fer hisself. While he does it, I walk up an down on my hands. It’s about th’only thing I can do that he cain’t. He pretends he don’t care, but I know he does.

You look funny upside down, I says.

Lugh’s golden hair gleams in the sun. He wears it tied back in one long braid that reaches almost to his waist. I wear mine the same, only my hair’s black as Nero’s feathers.

His necklace catches the light. I found the little ring of shiny green glass in the landfill an threaded it on a piece of leather. I gave it to him fer our eighteen year birthday an he ain’t took it off since.

What did he give me? Nuthin. Like always.

Okay I got a good one, he calls.

I go runnin over to take a look. Not as good as mine, I says.

I’m gonna skip eight today, he says. I feel it in my bones.

In yer dreams, I says. I’m callin a seven.

I whip my arm back an send the stone skimmin over the water. It skips once, twice, three times. Four, five, six. . .

Seven! I says. Seven! Didya see that?

I cain’t hardly believe it. I ain’t never done more’n five before.

Sorry, Lugh says. I warn’t lookin. Guess you’ll hafta do it agin.

What! My best ever an you didn’t . . . you rat! You did see! Yer jest sick with jealousy. I fold my arms over my chest. Go on. Let’s see you do eight. Betcha cain’t.

He does seven. Then I do my usual five. He’s jest pullin his arm back fer another try when, outta nowhere, Nero comes swoopin down at us, cawin his head off.

Damn bird, says Lugh, he made me drop my stone. He gits on his knees to look fer it.

Go away! I says, flappin my hands at Nero. Shoo, you bad boy! Go find somebody else to—

A dustcloud’s jest appeared on the horizon. A billowin orange mountain of dust. It’s so tall, it scrapes aginst the sun. It’s movin fast. Headed straight at us.

Uh . . . Lugh, I says.

There must be somethin in my voice. He looks up sharpish. Drops the stone in his hand. Gits slowly to his feet.

Holy crap, he says.

We jest stand there. Stand an stare. We git all kinda weather here. Hotwinds, firestorms, tornadoes, an once or twice we even had snow in high summer. So I seen plenty of dust storms. But never one like this.

That’s one bastard of a cloud, I says.

We better git outta here, says Lugh.

We start to back away slow, still starin. Then, Run, Saba! Lugh yells.

He grabs my hand, yankin at me till my feet move, an then we’re runnin. Runnin fer home, fast as wolfdogs on the hunt.

I look over my shoulder an git a shock. The dustcloud’s halfways across the lake. I never seen one move so fast. We got a minute, two at most, before it’s on us.

We cain’t outrun it! I yell at Lugh. It’s comin too fast!

The shanty comes into view an we start to shout an wave our arms.

Emmi’s still ridin around on her two-wheeler.

Pa! we scream. Pa! Emmi! Dust storm!

Pa appears in the doorway. Shades his eyes with his hand. Then he makes a dash fer Emmi, snatches her an runs full pelt fer the unnerground storm cellar.

The cellar ain’t more’n fifty paces from the shanty. He hauls up the wooden door set into the ground an drops Emmi inside. He waves his arms at us, frantic.

I look back. Gasp. The great mountain of orange dust races towards us with a roar. Like a ravenous beast, gobblin the ground as it goes.

Faster, Saba! Lugh yells. He rips off his shirt an starts wrappin it around his face.

Nero! I says. I stop, look all around. Where’s Nero?

No time! Lugh grabs my wrist, pulls at me.

Pa yells somethin I cain’t hear. He climbs into the storm cellar an pulls the door to.

I cain’t leave him out here! I pull myself free. Nero! I yell. Nero!

It’s too late! Lugh says. He’ll save hisself! C’mon!

A fork of lightnin slashes down an lands with a almighty crack an hiss.

One Missus Ippi, two Missus Ippi, three—

There’s a sullen rumble of thunder.

Less’n a league! Lugh says.

Everythin goes black. The cloud’s on us. I cain’t see a thing.

Lugh! I scream.

Hang on! he yells. Don’t let go!

The next thing I know, a tingle runs across my skin. I gasp. Lugh must feel it too because he lets go my hand like he’s bin scalded.

Lightnin’s comin! he yells. Git down!

We hunker down, some ways apart. We crouch as low to the ground as we can git. My heart’s stuck in my throat.

One more time, Saba. If lightnin catches you out in the open, whaddya do?

Crouch down, head down, feet together, hands on knees. Don’t let my hands or knees touch the ground. That’s right, ain’t it, Pa?

An never lie down. Don’t ferget that, Saba, never lie down.

I hear Pa’s voice loud an clear in my head. He got struck by lightnin as a boy. Nearly got killed from not knowin the right thing to do, so he’s made damn sure we all know what to—

Crack! The darkness splits open with a bright flash an a slam boom. It sends me flyin. I bang my head aginst the ground—hard. Try to pull myself up but fall back. Dizzy. My head spins round an round. I groan.

Saba! Lugh shouts. Are y’okay?

Another flash an boom splits the darkness. I think it’s headed away from us, but I cain’t be sure, my head’s so muddled. My ears ring.

Saba! Lugh yells. Where are you?

Over here! I call out, my voice all thin an shaky. I’m here!

An then Lugh’s there, kneelin beside me an pullin me up to sit.

Are you hurt? he says. Are y’okay? He slips his arm around me, helps me to stand. My legs feel all wobbly. Did it hit you?

I . . . uh . . . it . . . knocked me offa my feet, is all, I says.

Then, as we stand there, the dark rolls away.

An the world’s turned red.

Bright red like the heart of a fire. Everythin. The ground, the sky, the shanty, me, Lugh—all red. Fine red dust fills the air, touches every single thing. A red red world. I ain’t never seen nuthin like it before.

Me an Lugh stare at each other.

Looks like the end of the world, I says. My voice sounds muffled, like I’m talkin unner a blanket.

An then, outta that red dust haze, the men on horses appear.

† † †

There’s five of ’em. Ridin sturdy, shaggy coat mustangs.

Even in normal times we don’t git folk passin by Silverlake, so it’s a shock to see strangers blowin in on the tail of the worst dust storm in years. The horsemen pull up near the shanty. They don’t dismount. We start over.

Let me do the talkin, Lugh says.

Four of the riders is dressed in long black robes. They got on heavy leather vests strapped over top an sheemas wrapped round their heads. They’re dusted head to foot with red earth. As we git closer, I can see the fifth man’s our neighbor, Procter John. He’s ridin his horse, Hob.

As we come in earshot, Lugh calls out, Strange kinda day fer a ride, ain’t it, Procter John?

Nobody says nuthin. Their sheemas cover the riders’ faces so’s we cain’t see their expressions.

Now we’re right up near ’em.

Procter, Lugh nods. Who’s yer friends?

Procter still says naught. Jest stares down at his hands holdin the reins.

Look, I whisper to Lugh. Blood trickles out from unner Procter John’s hat, snakes down his face.

What’s goin on here? says Lugh. Procter? By the sound of his voice, I can tell he thinks somethin ain’t right about this. Me too. My heartbeat picks up.

Is this him? says one of the men to Procter John. Golden Boy here? Is he the one born at midwinter?

Procter John don’t look up. He nods. That be him, he says in a low voice.

How many years you got, boy? the man says to Lugh.

Eighteen, says Lugh. What’s it to you anyways?

An you was fer definite born at midwinter?

Yeah. Look, what’s all this about?

I told you he’s the right one, says Procter John. I should know. I bin keepin a eye on him all this time like you told me to. Can I go now?

The man nods.

Sorry, Lugh, says Procter John, still not lookin at us. They didn’t give me no choice.

He clicks Hob an makes to leave. The man slides a bolt shooter from his robe. I know he must be movin fast, but it all seems to go so slow. He pulls the trigger an shoots Procter. Hob rears in fright. Procter slides off an lands in a heap on the ground. He don’t move.

A cold jolt runs through me. We’re in trouble. I grab Lugh’s arm. The four men start movin towards us.

Fetch Pa, Lugh says. Quick. I’ll draw ’em away from the house.

No, I says. It’s too dangerous.

Move, gawdammit!

He turns. Starts runnin back towards the lake. The men heel their horses an head after him. I run like stink fer the storm cellar, fast as my feet’ll carry me.

Pa! I yell. Pa! Come quick!

I look over my shoulder. Lugh’s halfways to the lake. The four riders is spreadin out to make a big circle. Lugh

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...