- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

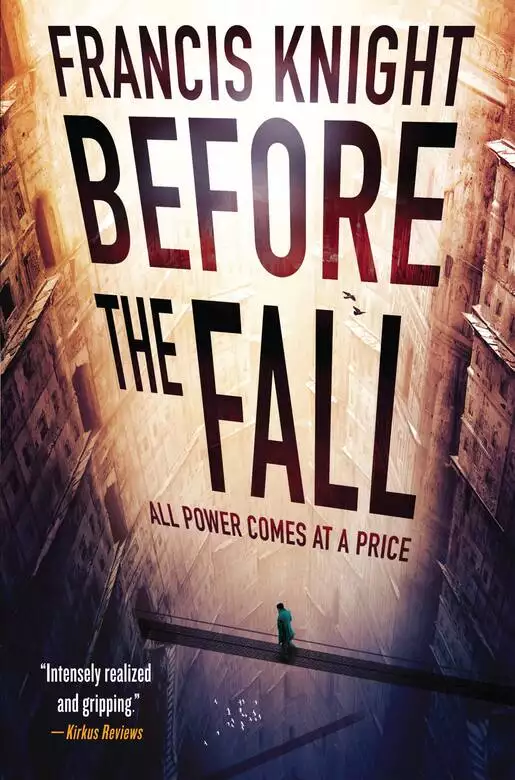

Synopsis

MAHALA IS A CITY OF CONTRASTS:

LIGHT AND DARK. HOPE AND DESPAIR.Rojan Dizon just wants to keep his head down. But his worst nightmare is around the corner.

With the destruction of their power source, his city is in crisis: riots are breaking out, mages are being murdered, and the city is divided. But Rojan's hunt for the killers will make him responsible for all-out anarchy. Either that, or an all-out war.

And there's nothing Rojan hates more than being responsible.

The fantastic follow-up to FADE TO BLACK!

Release date: June 18, 2013

Publisher: Orbit

Print pages: 288

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Close

Before the Fall

Francis Knight

No-Hope-Shitty: the name says it all really. This particular part of the city, so far down it was almost the even-worse Boundary, was one of the crappier shit-pits. The smell of hopelessness, fear and the sweat of too many people seemed ground into the dank buildings that crammed every available space.

I made my way along a swaying walkway that was only nominally attached to the clutch of gently mouldering boxes they called houses down here and tried not to think how far down the gap underneath went. To keep my mind off the drop, I swore at Dendal in my head. Some damn-fool notion he’d had was why I was here in the arse end of the city. Trying to find someone I wasn’t even sure existed in a maze of synth-ridden houses and rotting walkways that looked as though they’d turn on me at any time and dump me down twenty, thirty, floors to the bottom of Boundary, or even further to the newly opened ’Pit–to Downside.

Heights, or, rather, depths, make me nervous and nervous makes me cranky, so I kept on swearing at Dendal in my head. Downsider music, all wailing voices and thumping drums, rattled crumbling walls unused to anything more raucous than the occasional bland hymn. Wary eyes peered out at me from cracked windows. Here was somewhere I really didn’t want to be, not an Upsider like me. The whole area was crammed with recent Downsider refugees, fearful, and not without cause.

I’d ditched my usual outfit: the leather allover and the flapping jacket that made me look like a Special. It was handy for scaring the crap out of people, but Downsiders had a particular hatred for the elite guards and that hatred was just as likely to overcome the fear that was radiating through the thin walls. I am many things but suicidal isn’t one of them, so I’d dressed to blend in with an old-fashioned button-up shirt and a pair of tatty trousers I’d found that didn’t quite fit. Just another guy feeling his way in this new and strange part of a city most of the Downsiders hadn’t even seen before a couple of months ago. To them, the Upside of Mahala was the mythical come true, the alien place where things and people were weird. I kept having to remind myself of that. I’d even tried my best with my face, tried to give myself that Downsider blue-white undertone to my skin, rearranged things so I didn’t look as threatening.

That disguise had its drawbacks, though. I’d been scowled at, sniffed at, spat on and sworn at on my way here. The sudden influx of refugees into Upside–only into the less salubrious areas such as No-Hope, but still–on top of the demise of our major power source and the resulting loss of trade, jobs, food and everything else, had made everyone, Upsider and Down, tense. There had been incidents all over just lately, from both sides, events that made parts of No-Hope a dangerous place for someone like me, for anyone not a Downsider. They’d also made other places just as dangerous for the refugees. If I showed my real face here, if they knew it was me who had caused all those things, I’d have been pitched over the side of the walkway before I’d taken half a dozen steps from the office.

I stopped on a corner between a boarded-up apothecary and a little grocery store that had run out of even really crappy food, wishing I’d brought a light of some kind, but candles were scarcer than food then, and I don’t like to use rend-nut oil. The mingled smell of rotting fish and day-old farts wasn’t a nice kind of aftershave and doesn’t pull in the chicks. Sadly, it was that or nothing, so I went with nothing.

Since the Glow had been destroyed by yours truly, power was at a premium. Down this far in the city sun was a rumour. It wasn’t much past noon up in the rarefied air of Over Trade. In Heights and Clouds and Top of the World, Ministry lived in the sun, shielding it, stealing it from us dregs. That much hadn’t changed–yet. It might never. Down here in Under, beneath the factories and warehouses of Trade that were eerily silent now, it might as well have been midnight. Even the cunning network of mirrors and twisted light wells that gave my office a shred of real, actual sunlight for about three minutes around noon and an almost constant dusk for the rest of the day, failed this far down.

I told myself that I didn’t need light for what I was here for. True, I didn’t. Rather, what I needed was pain, my pain. Which was a bitch, but I’d tried everything else, and everything else hadn’t worked. Dendal was waiting and I didn’t like to disappoint, and not just because he’s my landlord and boss. He’s my boss because if he concentrated he could spread me over a large portion of the city. He could do it accidentally too, which was more likely, but I always found it best not to make him wait. He gets all insistent about his little obsessions and it’s easiest just to go along. Besides, I owe him a couple of legs, in that without his help I probably would have blown mine off long since while I learnt my magic. So, here I was.

The boy Dendal was after was a Downsider refugee; no records, no known address, not even a name to go on. All I had was a scrap of cloth and a hunch of Dendal’s. It was magic, or nothing.

Left to my own devices, I’d have said screw the little sod and abandoned him to fend for himself, no better or worse off than thousands of others quietly starving to death in the dark down here. Responsible isn’t high on my list of qualities. In fact, I usually try to make sure it doesn’t even appear on the list. But Dendal’s persuasive, and also really good at guilt-tripping me even if he doesn’t mean to. I hoped he would appreciate it, because this was going to hurt, and I don’t like to hurt.

With my good hand, I rummaged in my pocket for the scrap of cloth Dendal had given me. There wasn’t anywhere to sit that didn’t involve what was probably synth-tainted water. The damn stuff still lingered, still made people sick from the inside out even now, so I crouched down and leant back against a rickety wall that I hoped would take my weight. I was getting better at this, but still had a tendency to end up on my knees when I tried because it usually felt as though I was about to pop an eyeball, or perhaps a bollock.

I laid the scrap of cloth on my lap and stroked it with my good hand. My anchor, that cloth, the little bit of someone that would help me find them, in this case a boy. If I didn’t know someone well then I needed a prop to help me find them–something of theirs usually, something intimate to them.

On the plus side, I didn’t need to dislocate my thumb to power up my magic today. On the minus side, that was because I’d fucked up my whole left hand in the incident that had led to all the Glow disappearing. The hand was still healing and all I needed to do was try to make a tight fist to have white spots run in front of my eyes and power run through my veins. There has to be a better way to cast a find spell–any kind of spell–but I haven’t figured out what it is yet. When I do, they’ll hear the halle-fucking-lujah from Top of the World all the way down to the bottom of the ’Pit.

I made a fist and pain spiked through me along with magic, sweet and alluring, and oh so dangerous. It spun around me, through me, calling, always calling. In and out, quick as I could, that was the best way. Before it tempted me, before the black rushed up to claim me. I’d beaten the black before, once, but I wasn’t so sure I could do it again. It was always there, waiting to trap the unwary, seductive and tempting. The price of my magic wasn’t pain, it was the threat of falling into the black and never coming out, of losing my fragile sanity to it.

It came quickly, flowing up my arm from the scrap of cloth–the sure and certain knowledge that the boy was to the east, a hundred yards away and two levels down. The pungent smell of a rend-nut oil lamp overlaying the more insidious chemical tang of synth, an ominous flicker of shadows. Even more ominous-looking men. Four Upsiders in a half-circle around a boy on the ground. Upsiders who looked seriously pissed off. One of them made a grab for the boy and a knife gleamed in his other hand. In that gleam I thought I saw the rumour that was spreading everywhere but officially. Someone was killing Downsiders, and not just in fights either. Three dead boys already, and this looked like another in the making. No wandering along the walkways to find this particular boy; not now, not if I wanted to find him alive.

See, now this is why I don’t like responsibility. Not only does my magic hurt like fuck, now it seemed I was going to have to risk a stabbing and I really liked that shirt. It would certainly look better without my blood on it. I could have left the boy, I could have turned away. It certainly would have been better for my health. But, despite what my exes will tell you, at length and in gruesome detail, I am not completely heartless. Only mostly. Besides, we needed this boy if what Dendal suspected was true.

Muttering under my breath about fucking Dendal and his fancy fucking notions of fucking charity, I clenched my fist tighter. The black sidled up behind me like a thief, waiting for its chance to drag me into its madness, its joy. Come on, Rojan, you know you want me, you need me.

“I’m not afraid of you,” I lied. “So fuck off.”

Pain was everything, magic was everything, every part of me. Universes were born, spun across my vision and died. I knew I was going to regret this but I shut my eyes, let the where of the boy seep in. The rend-nut stench grew stronger, surrounded me and made me gag. The air grew danker, colder. One final squeeze of my hand that had me groaning and then I opened my eyes and tried not to throw up.

A ring of very surprised faces in the flickering dark. Not very happy faces. I had, of course, announced that I was a mage about as subtly as having a big flashing arrow pointing at my throat saying “Please rip here”, which, all things considered, could be said to be a Very Bad Idea. Way to go, Rojan, always leaping before you look.

The man with the knife recovered from his surprise the quickest and loomed over me with a menace that seemed to come naturally.

I always come prepared.

I didn’t fancy any more pain so I pulled my gun, pressed the end of the barrel against his nose and made a show of cocking it. Everyone stopped. Guns were still new enough, still expensive and rare enough, that I was pretty confident I had the only one for half a mile in any direction. “Hello. Anyone want to tell me what the fuck they think they’re doing?”

Knife-man took two slow, careful steps backwards, but he didn’t lower the blade. A quick glance round and I realised why. In my rush towards responsibility I had failed to see the other men outside the circle. The crowd of them behind me. Looking big and mean and very ugly. I’d heard of this in whispers, of Upsiders going around mob-handed into the refugee areas when it was quiet, finding some poor Downsider on his own and stomping him before getting the hell out. Of them boasting about it afterwards in Upsider bars. Is it any wonder I’m such a cynic?

Three of the men stepped forward. I’m a fairly big guy, broad enough with it, and I can look threatening when I need to, but these guys had it down to an art. A mean look to them, like they probably kicked their way out of their mothers’ wombs, head-butted the midwife and then got stuck into mugging their parents and strangling the cat.

I was beginning to wish I hadn’t bothered getting out of bed that morning, or that I’d never met Dendal, or even that I’d stayed dead when I’d had the chance.

The boy crouched by my feet, dripping sweat and fear.

“In my pocket,” I said. “Left-hand side.”

He didn’t hesitate, but delved into the pocket and pulled out my pulse pistol. A very specialised and until recently ever so slightly illegal piece of kit. The kid stared at it for a moment as if it were a live snake before he seemed to get a grip of himself, and the pistol.

The Upsiders were moving in, wary, careful, but closer every second. I risked a glance behind: a shabby door that looked half eaten by synth and damp. I backed towards it and the boy came with me. He was shaking fit to bust and what happened next was probably inevitable.

He pulled the trigger. Now, a pulse pistol is, as I said, a specialised piece of kit. It doesn’t fire bullets, it fires magic, at least provided it’s a mage pulling the trigger.

Dendal had been right about the boy. He fired, the razor flipped out and sliced his thumb and the whirring mechanism took the pain, the magic, magnified it and blasted it out of the end.

I imagine the Upsiders were ever so grateful that it was non-lethal. Eventually grateful, at least. The pulse leapt out and jumped from one to another, far more power there than anything I’d ever been able to coax out of it. The zapping pulse dropped everyone it touched, shorting out their brains and sending them slumping to the dilapidated floor to wallow in shallow synth-tainted pools.

The boy had let out a yelp when the razor cut his thumb, but now he stood as though his own brain was shorted out, staring dumbly at the pile of limp bodies.

We didn’t have time for that. The pistol knocks them out but they soon wake up again, and I only had one set of cuffs on me.

I made a mental note to congratulate Dwarf on the improvements he’d made to the pulse pistol, grabbed the boy and made a run for it. Courageous to the end, that’s me.

It took some persuading to get the boy to come with me–I’d saved him from a good kicking, or worse, but he knew from my voice I was an Upsider and from his point of view that meant I was a bastard. I can’t say he was wrong, but I can be persuasive when I want to be, not to mention he was half starved and I had come prepared with food. Not much, and it was a crap not much, but it was all we could find, all there was. He shovelled it in like he’d not eaten in a week, which he probably hadn’t, and followed me with a suspicious scowl that said he’d be off at the first hint of trouble.

Mesh walkways crisscrossed above us, leaving no shadow in the gloom. They sagged away from walls, dripped who knows what down our necks. The further we got away from the ’Pit that Downsiders had once called home, the more jittery the boy became. At least once we got to the level of the office, the walkways were firmer–but the drop was longer. Further up the buildings get less squashed looking, but down here the weight of the city above, below, all around, was a pressure you could feel in your bones.

By the time I got the boy back to our new offices it had begun to rain, a slow cold seeping through all the levels above us, a steady drip that always seemed to find the crevices in your jacket or around your neck to sidle into. We’d had to move office because being associated with the old me was now a dangerous thing. I have this way with people–I’m great at really pissing them off, and this time I’d outdone myself. Whole battalions of Upsiders were pissed with me, or would be if they found out I was still alive. The Downsiders weren’t far behind and, to top it off, most of the ruling Ministry, while unofficially ignoring the fact I was still alive, would be pleased if I ended up in lots of small, messy bits. So currently I was not me, Rojan, bounty hunter, pain-mage, shirker of responsibility, pathological womaniser and physical coward. I was Makisig, Maki for short. I was still all the other things, though I was trying to be subtle about them. Especially the mage bit. We’d only been legal a few weeks but there was still a hell of a lot of hate about, and legal isn’t the same as safe.

Dendal had a knack for picking sodding awful offices, too. This one had previously been a front for a Rapture dealer and off-their-faces lowlives had a habit of wandering in and asking if they could score. Some of them got quite unhappy when all they got was a lecture from Dendal about the evils of drugs, beer, sex and anything else he could think of before he sent them on to the other huge drawback of the offices.

The temple next door.

I could hear them now, chanting and praying their sanitised, Ministry-approved prayers. People playing with their imaginary friend. Not that I would ever say that to Dendal. He gets very focused when the Goddess is involved. I suppose a bit of faith gave people hope, which was about all that could be said for it. They needed hope now more than ever.

At least we were far up enough that some of the little power there was ran a light at the end of the street, so even if we didn’t see more than a minute or two of the sun at noon, and a hazy fourth-hand light after that, bounced down through the mirrors, we could see where we were going. Sometimes I wished we didn’t have the light; all it illuminated was grubby, damp and depressing.

I aimed the boy at the office door. He would come in handy as a shield against Lastri–secretary, harridan and person who made sure Dendal ate occasionally and didn’t bump into anything too hard while he was away with the fairies. Also one of the very few women over eighteen and under about forty-five I’ve ever met who, despite her severe and primly attractive features, I have never tried to talk into bed. I’d never make it out alive.

She smiled at the boy as we came in, put a motherly hand around his shoulder and steered him to the small kitchen at the back while flinging me a look that said it hoped I strangled myself in my sleep.

Dendal was at his desk in the corner; he always was. His grey hair puffed round him like an errant cloud and his thin, monk-like face was pinched in what looked like concentration but might just as likely have been a daydream. More likely even. Paperwork surrounded him, as did an array of candles that put the temple next door to shame. I said a quick hello and got a vague, dreamy look in return. Not quite with it, our Dendal. Oh, he’s a genius all right, smartest mage I ever met. When he’s anywhere approaching reality that is, which is about once a week if I’m lucky.

“Hello, Perak,” he murmured. At least he’d got the gender right, if not the sibling. Then something on one of his pieces of paper caught his eye and he burrowed into his little fairyland again. He only really concentrated on his messages. To him it was his Goddess-given duty whether he used his magic or not, to help people communicate. It looked like today he was up to the more mundane pastime of writing letters for the majority of people around here who couldn’t. No magic, no dislocated fingers, just Dendal’s vague tuneless hum and the scritch-scratch of pen on paper that had been part of my life for so long I only noticed it when it stopped.

So far, so normal.

I chucked my jacket on to the sofa squashed in the corner, patted Griswald, the stuffed tiger, on the head and aimed for my desk. At least the boy hadn’t generated any paperwork, for which I was thankful. I checked the desk carefully, making sure it hadn’t laid any ambushes for me, and sat down, ready to do something about my hand. At this rate it was never going to heal, what with finding people and my little sideline at Dwarf’s lab.

One of Lastri’s pointed notes sat on the desktop, a superior sneer in the slope of the handwriting. Another boy to find but at least I had a name to go on, so maybe I could get away with just searching some records rather than buggering up my hand any more than I already had. It would have been even better if someone was actually paying me for all this searching, but all I’d got so far was Dendal’s assurance that I was doing the Goddess’s work. All very well, but she wasn’t paying my rent. Luckily the landlord–Dendal–tended to forget what I owed, though Lastri was distressingly accurate, not to mention insistent.

The other reason for the change of offices, an extra partner in our motley little crew, sat at his desk. Pasha still had a face like a sulky monkey nesting in a rumple of dark hair, but since the Glow had gone, and with it the ill-gotten pain that powered it, he’d seemed to grow. Less jumpy now, but still plenty angry.

He looked up from the news-sheet he’d been scowling over. “What happened to you? You look like shit.”

He was still a git. I braved the vagaries of my desk drawer. The trick was to open it up, grab what you wanted and get your hand out quick, before it realised what you were doing and slammed shut. It was unreasonably possessive of its contents, I felt, and I only had one good hand left anyway.

I managed to get out the mirror without incurring any broken bones and studied my reflection. Pasha was right: I did look like shit. I would like to point out that the mirror was a new thing and not lurking in my drawer because I’m incredibly vain. Well, I am quite vain, but that’s not why it was there. No, it was there because of the new direction my magic had taken, and because a lot of people thought I was dead and I wanted it to stay that way, or I would be.

I still had a bit of juice left from my earlier hand-mangling so I did the best I could to tidy myself up, rearranging my face back to my more usual disguise. It’s weird seeing someone else’s face in the mirror every day, but better than being dead. I only let the disguise drop when I slept, or when I shaved. Shaving the wrong-shaped face is hard and, I’d discovered, usually ends in blood and swearing.

I couldn’t do anything about the rather spectacular shiner, though. My new skills weren’t up to that yet, in the same way that I couldn’t rearrange my voice, though I was working on it.

Pasha wandered over, sat on the edge of the desk and grinned his monkey grin. I couldn’t help but like him, no matter how hard I tried not to.

“So, who gave you that and why did you let them?”

“She caught me by surprise. I’ve decided to give up women.”

His snorted in disbelief before he closed his eyes and twisted his hands in his lap.

“You can stop that as well. I told you: you don’t read my mind, I won’t permanently rearrange your face.” It came out sharper than I’d intended, mainly because I didn’t want him figuring out just why the lady in question had belted me one. And the lady before that and, come to think of it, the lady before that as well. Let’s just say, saying the wrong name at a delicate moment isn’t a good move and leave it at that. I was definitely swearing off women. Definitely, for sure this time.

The Kiss of Death, Lastri calls me. I never mean to, but I kill any budding relationship stone dead. Usually it was for more varied reasons, granted. Being unable to resist temptation tops the list. Like responsibility, willpower rarely makes it on to my list of good points. Why deny all those women their chance? So many, and all so lovely…

My wandering eyes had stilled for a while, but were back to their old tricks in something like self-defence for my heart, which, if I’m brutally honest, was as mangled as my hand. Playing my old games took my mind off that, meant I didn’t need to think about it, what I’d lost and Pasha had gained.

Pasha took the hint and changed the subject. “So, the boy, you found him? Any joy?”

“Found him, and, yes, he’s a pain-mage all right. Lastri’s feeding him up, I expect. Built like a stick, and he was about to get the crap kicked out of him by a load of Upsiders. Makes me wonder what the little sod’s done.”

Pasha gave me a cryptic look, but the words were pure viciousness. “Was born, perhaps. Had the audacity to come up here when we stopped the Glow and opened the ’Pit. Got the wrong skin tone, the wrong accent, worships the wrong way. Take your pick.”

His tone took me aback–Pasha looked like a monkey that’s lost its nut, but he could be a lion when he wanted to be, and he would always roar in the defence of Downsiders.

I hadn’t meant it that way; it had just come out as part of my sparkling and charming personality because I was pissed at having to use my magic, but I was still getting used to Pasha’s way of looking at things. “I don’t think––”

“No, I’ve noticed.”

I did think then, though. All the insults when I’d worn a Downsider face, the snarls and spits. The rumours of the Upsider gangs stomping lone Downsiders. Pasha still had it, that blue-white tone lurking under dusky skin. Brought up in the ’Pit with no sun, not even the few minutes a day someone Upside managed. You could usually tell a Downsider at a glance, and the accent was what really gave them away. Given that the Ministry would rather they weren’t here, the embarrassment of them even existing when they’d been denied for decades, the chances of them getting a look at the real sun from up in Heights or above was slim. It might take years for that unearthly pallor to go. It might never go.

“You seen this?” Pasha slapped down the news-sheet he’d been reading on my desk. I caught sight of the headline: DOWNSIDERS SPREAD NEW DISEASE. Near the bottom was another article about Downsiders scattering malicious rumours of what had gone on in the ’Pit, and how it wasn’t true, followed by a frankly laughable account of what had “really” happened. Which, naturally, given that this was a shadow–not officially sanctioned, but a mouthpiece for some of their more vocal ministers–Ministry news-sheet, was a load of old bollocks. As was the bit about mages and our unholy ways and it was all our fault. Well, it was mostly untrue. I am fairly unholy. And I had screwed ever. . .

I made my way along a swaying walkway that was only nominally attached to the clutch of gently mouldering boxes they called houses down here and tried not to think how far down the gap underneath went. To keep my mind off the drop, I swore at Dendal in my head. Some damn-fool notion he’d had was why I was here in the arse end of the city. Trying to find someone I wasn’t even sure existed in a maze of synth-ridden houses and rotting walkways that looked as though they’d turn on me at any time and dump me down twenty, thirty, floors to the bottom of Boundary, or even further to the newly opened ’Pit–to Downside.

Heights, or, rather, depths, make me nervous and nervous makes me cranky, so I kept on swearing at Dendal in my head. Downsider music, all wailing voices and thumping drums, rattled crumbling walls unused to anything more raucous than the occasional bland hymn. Wary eyes peered out at me from cracked windows. Here was somewhere I really didn’t want to be, not an Upsider like me. The whole area was crammed with recent Downsider refugees, fearful, and not without cause.

I’d ditched my usual outfit: the leather allover and the flapping jacket that made me look like a Special. It was handy for scaring the crap out of people, but Downsiders had a particular hatred for the elite guards and that hatred was just as likely to overcome the fear that was radiating through the thin walls. I am many things but suicidal isn’t one of them, so I’d dressed to blend in with an old-fashioned button-up shirt and a pair of tatty trousers I’d found that didn’t quite fit. Just another guy feeling his way in this new and strange part of a city most of the Downsiders hadn’t even seen before a couple of months ago. To them, the Upside of Mahala was the mythical come true, the alien place where things and people were weird. I kept having to remind myself of that. I’d even tried my best with my face, tried to give myself that Downsider blue-white undertone to my skin, rearranged things so I didn’t look as threatening.

That disguise had its drawbacks, though. I’d been scowled at, sniffed at, spat on and sworn at on my way here. The sudden influx of refugees into Upside–only into the less salubrious areas such as No-Hope, but still–on top of the demise of our major power source and the resulting loss of trade, jobs, food and everything else, had made everyone, Upsider and Down, tense. There had been incidents all over just lately, from both sides, events that made parts of No-Hope a dangerous place for someone like me, for anyone not a Downsider. They’d also made other places just as dangerous for the refugees. If I showed my real face here, if they knew it was me who had caused all those things, I’d have been pitched over the side of the walkway before I’d taken half a dozen steps from the office.

I stopped on a corner between a boarded-up apothecary and a little grocery store that had run out of even really crappy food, wishing I’d brought a light of some kind, but candles were scarcer than food then, and I don’t like to use rend-nut oil. The mingled smell of rotting fish and day-old farts wasn’t a nice kind of aftershave and doesn’t pull in the chicks. Sadly, it was that or nothing, so I went with nothing.

Since the Glow had been destroyed by yours truly, power was at a premium. Down this far in the city sun was a rumour. It wasn’t much past noon up in the rarefied air of Over Trade. In Heights and Clouds and Top of the World, Ministry lived in the sun, shielding it, stealing it from us dregs. That much hadn’t changed–yet. It might never. Down here in Under, beneath the factories and warehouses of Trade that were eerily silent now, it might as well have been midnight. Even the cunning network of mirrors and twisted light wells that gave my office a shred of real, actual sunlight for about three minutes around noon and an almost constant dusk for the rest of the day, failed this far down.

I told myself that I didn’t need light for what I was here for. True, I didn’t. Rather, what I needed was pain, my pain. Which was a bitch, but I’d tried everything else, and everything else hadn’t worked. Dendal was waiting and I didn’t like to disappoint, and not just because he’s my landlord and boss. He’s my boss because if he concentrated he could spread me over a large portion of the city. He could do it accidentally too, which was more likely, but I always found it best not to make him wait. He gets all insistent about his little obsessions and it’s easiest just to go along. Besides, I owe him a couple of legs, in that without his help I probably would have blown mine off long since while I learnt my magic. So, here I was.

The boy Dendal was after was a Downsider refugee; no records, no known address, not even a name to go on. All I had was a scrap of cloth and a hunch of Dendal’s. It was magic, or nothing.

Left to my own devices, I’d have said screw the little sod and abandoned him to fend for himself, no better or worse off than thousands of others quietly starving to death in the dark down here. Responsible isn’t high on my list of qualities. In fact, I usually try to make sure it doesn’t even appear on the list. But Dendal’s persuasive, and also really good at guilt-tripping me even if he doesn’t mean to. I hoped he would appreciate it, because this was going to hurt, and I don’t like to hurt.

With my good hand, I rummaged in my pocket for the scrap of cloth Dendal had given me. There wasn’t anywhere to sit that didn’t involve what was probably synth-tainted water. The damn stuff still lingered, still made people sick from the inside out even now, so I crouched down and leant back against a rickety wall that I hoped would take my weight. I was getting better at this, but still had a tendency to end up on my knees when I tried because it usually felt as though I was about to pop an eyeball, or perhaps a bollock.

I laid the scrap of cloth on my lap and stroked it with my good hand. My anchor, that cloth, the little bit of someone that would help me find them, in this case a boy. If I didn’t know someone well then I needed a prop to help me find them–something of theirs usually, something intimate to them.

On the plus side, I didn’t need to dislocate my thumb to power up my magic today. On the minus side, that was because I’d fucked up my whole left hand in the incident that had led to all the Glow disappearing. The hand was still healing and all I needed to do was try to make a tight fist to have white spots run in front of my eyes and power run through my veins. There has to be a better way to cast a find spell–any kind of spell–but I haven’t figured out what it is yet. When I do, they’ll hear the halle-fucking-lujah from Top of the World all the way down to the bottom of the ’Pit.

I made a fist and pain spiked through me along with magic, sweet and alluring, and oh so dangerous. It spun around me, through me, calling, always calling. In and out, quick as I could, that was the best way. Before it tempted me, before the black rushed up to claim me. I’d beaten the black before, once, but I wasn’t so sure I could do it again. It was always there, waiting to trap the unwary, seductive and tempting. The price of my magic wasn’t pain, it was the threat of falling into the black and never coming out, of losing my fragile sanity to it.

It came quickly, flowing up my arm from the scrap of cloth–the sure and certain knowledge that the boy was to the east, a hundred yards away and two levels down. The pungent smell of a rend-nut oil lamp overlaying the more insidious chemical tang of synth, an ominous flicker of shadows. Even more ominous-looking men. Four Upsiders in a half-circle around a boy on the ground. Upsiders who looked seriously pissed off. One of them made a grab for the boy and a knife gleamed in his other hand. In that gleam I thought I saw the rumour that was spreading everywhere but officially. Someone was killing Downsiders, and not just in fights either. Three dead boys already, and this looked like another in the making. No wandering along the walkways to find this particular boy; not now, not if I wanted to find him alive.

See, now this is why I don’t like responsibility. Not only does my magic hurt like fuck, now it seemed I was going to have to risk a stabbing and I really liked that shirt. It would certainly look better without my blood on it. I could have left the boy, I could have turned away. It certainly would have been better for my health. But, despite what my exes will tell you, at length and in gruesome detail, I am not completely heartless. Only mostly. Besides, we needed this boy if what Dendal suspected was true.

Muttering under my breath about fucking Dendal and his fancy fucking notions of fucking charity, I clenched my fist tighter. The black sidled up behind me like a thief, waiting for its chance to drag me into its madness, its joy. Come on, Rojan, you know you want me, you need me.

“I’m not afraid of you,” I lied. “So fuck off.”

Pain was everything, magic was everything, every part of me. Universes were born, spun across my vision and died. I knew I was going to regret this but I shut my eyes, let the where of the boy seep in. The rend-nut stench grew stronger, surrounded me and made me gag. The air grew danker, colder. One final squeeze of my hand that had me groaning and then I opened my eyes and tried not to throw up.

A ring of very surprised faces in the flickering dark. Not very happy faces. I had, of course, announced that I was a mage about as subtly as having a big flashing arrow pointing at my throat saying “Please rip here”, which, all things considered, could be said to be a Very Bad Idea. Way to go, Rojan, always leaping before you look.

The man with the knife recovered from his surprise the quickest and loomed over me with a menace that seemed to come naturally.

I always come prepared.

I didn’t fancy any more pain so I pulled my gun, pressed the end of the barrel against his nose and made a show of cocking it. Everyone stopped. Guns were still new enough, still expensive and rare enough, that I was pretty confident I had the only one for half a mile in any direction. “Hello. Anyone want to tell me what the fuck they think they’re doing?”

Knife-man took two slow, careful steps backwards, but he didn’t lower the blade. A quick glance round and I realised why. In my rush towards responsibility I had failed to see the other men outside the circle. The crowd of them behind me. Looking big and mean and very ugly. I’d heard of this in whispers, of Upsiders going around mob-handed into the refugee areas when it was quiet, finding some poor Downsider on his own and stomping him before getting the hell out. Of them boasting about it afterwards in Upsider bars. Is it any wonder I’m such a cynic?

Three of the men stepped forward. I’m a fairly big guy, broad enough with it, and I can look threatening when I need to, but these guys had it down to an art. A mean look to them, like they probably kicked their way out of their mothers’ wombs, head-butted the midwife and then got stuck into mugging their parents and strangling the cat.

I was beginning to wish I hadn’t bothered getting out of bed that morning, or that I’d never met Dendal, or even that I’d stayed dead when I’d had the chance.

The boy crouched by my feet, dripping sweat and fear.

“In my pocket,” I said. “Left-hand side.”

He didn’t hesitate, but delved into the pocket and pulled out my pulse pistol. A very specialised and until recently ever so slightly illegal piece of kit. The kid stared at it for a moment as if it were a live snake before he seemed to get a grip of himself, and the pistol.

The Upsiders were moving in, wary, careful, but closer every second. I risked a glance behind: a shabby door that looked half eaten by synth and damp. I backed towards it and the boy came with me. He was shaking fit to bust and what happened next was probably inevitable.

He pulled the trigger. Now, a pulse pistol is, as I said, a specialised piece of kit. It doesn’t fire bullets, it fires magic, at least provided it’s a mage pulling the trigger.

Dendal had been right about the boy. He fired, the razor flipped out and sliced his thumb and the whirring mechanism took the pain, the magic, magnified it and blasted it out of the end.

I imagine the Upsiders were ever so grateful that it was non-lethal. Eventually grateful, at least. The pulse leapt out and jumped from one to another, far more power there than anything I’d ever been able to coax out of it. The zapping pulse dropped everyone it touched, shorting out their brains and sending them slumping to the dilapidated floor to wallow in shallow synth-tainted pools.

The boy had let out a yelp when the razor cut his thumb, but now he stood as though his own brain was shorted out, staring dumbly at the pile of limp bodies.

We didn’t have time for that. The pistol knocks them out but they soon wake up again, and I only had one set of cuffs on me.

I made a mental note to congratulate Dwarf on the improvements he’d made to the pulse pistol, grabbed the boy and made a run for it. Courageous to the end, that’s me.

It took some persuading to get the boy to come with me–I’d saved him from a good kicking, or worse, but he knew from my voice I was an Upsider and from his point of view that meant I was a bastard. I can’t say he was wrong, but I can be persuasive when I want to be, not to mention he was half starved and I had come prepared with food. Not much, and it was a crap not much, but it was all we could find, all there was. He shovelled it in like he’d not eaten in a week, which he probably hadn’t, and followed me with a suspicious scowl that said he’d be off at the first hint of trouble.

Mesh walkways crisscrossed above us, leaving no shadow in the gloom. They sagged away from walls, dripped who knows what down our necks. The further we got away from the ’Pit that Downsiders had once called home, the more jittery the boy became. At least once we got to the level of the office, the walkways were firmer–but the drop was longer. Further up the buildings get less squashed looking, but down here the weight of the city above, below, all around, was a pressure you could feel in your bones.

By the time I got the boy back to our new offices it had begun to rain, a slow cold seeping through all the levels above us, a steady drip that always seemed to find the crevices in your jacket or around your neck to sidle into. We’d had to move office because being associated with the old me was now a dangerous thing. I have this way with people–I’m great at really pissing them off, and this time I’d outdone myself. Whole battalions of Upsiders were pissed with me, or would be if they found out I was still alive. The Downsiders weren’t far behind and, to top it off, most of the ruling Ministry, while unofficially ignoring the fact I was still alive, would be pleased if I ended up in lots of small, messy bits. So currently I was not me, Rojan, bounty hunter, pain-mage, shirker of responsibility, pathological womaniser and physical coward. I was Makisig, Maki for short. I was still all the other things, though I was trying to be subtle about them. Especially the mage bit. We’d only been legal a few weeks but there was still a hell of a lot of hate about, and legal isn’t the same as safe.

Dendal had a knack for picking sodding awful offices, too. This one had previously been a front for a Rapture dealer and off-their-faces lowlives had a habit of wandering in and asking if they could score. Some of them got quite unhappy when all they got was a lecture from Dendal about the evils of drugs, beer, sex and anything else he could think of before he sent them on to the other huge drawback of the offices.

The temple next door.

I could hear them now, chanting and praying their sanitised, Ministry-approved prayers. People playing with their imaginary friend. Not that I would ever say that to Dendal. He gets very focused when the Goddess is involved. I suppose a bit of faith gave people hope, which was about all that could be said for it. They needed hope now more than ever.

At least we were far up enough that some of the little power there was ran a light at the end of the street, so even if we didn’t see more than a minute or two of the sun at noon, and a hazy fourth-hand light after that, bounced down through the mirrors, we could see where we were going. Sometimes I wished we didn’t have the light; all it illuminated was grubby, damp and depressing.

I aimed the boy at the office door. He would come in handy as a shield against Lastri–secretary, harridan and person who made sure Dendal ate occasionally and didn’t bump into anything too hard while he was away with the fairies. Also one of the very few women over eighteen and under about forty-five I’ve ever met who, despite her severe and primly attractive features, I have never tried to talk into bed. I’d never make it out alive.

She smiled at the boy as we came in, put a motherly hand around his shoulder and steered him to the small kitchen at the back while flinging me a look that said it hoped I strangled myself in my sleep.

Dendal was at his desk in the corner; he always was. His grey hair puffed round him like an errant cloud and his thin, monk-like face was pinched in what looked like concentration but might just as likely have been a daydream. More likely even. Paperwork surrounded him, as did an array of candles that put the temple next door to shame. I said a quick hello and got a vague, dreamy look in return. Not quite with it, our Dendal. Oh, he’s a genius all right, smartest mage I ever met. When he’s anywhere approaching reality that is, which is about once a week if I’m lucky.

“Hello, Perak,” he murmured. At least he’d got the gender right, if not the sibling. Then something on one of his pieces of paper caught his eye and he burrowed into his little fairyland again. He only really concentrated on his messages. To him it was his Goddess-given duty whether he used his magic or not, to help people communicate. It looked like today he was up to the more mundane pastime of writing letters for the majority of people around here who couldn’t. No magic, no dislocated fingers, just Dendal’s vague tuneless hum and the scritch-scratch of pen on paper that had been part of my life for so long I only noticed it when it stopped.

So far, so normal.

I chucked my jacket on to the sofa squashed in the corner, patted Griswald, the stuffed tiger, on the head and aimed for my desk. At least the boy hadn’t generated any paperwork, for which I was thankful. I checked the desk carefully, making sure it hadn’t laid any ambushes for me, and sat down, ready to do something about my hand. At this rate it was never going to heal, what with finding people and my little sideline at Dwarf’s lab.

One of Lastri’s pointed notes sat on the desktop, a superior sneer in the slope of the handwriting. Another boy to find but at least I had a name to go on, so maybe I could get away with just searching some records rather than buggering up my hand any more than I already had. It would have been even better if someone was actually paying me for all this searching, but all I’d got so far was Dendal’s assurance that I was doing the Goddess’s work. All very well, but she wasn’t paying my rent. Luckily the landlord–Dendal–tended to forget what I owed, though Lastri was distressingly accurate, not to mention insistent.

The other reason for the change of offices, an extra partner in our motley little crew, sat at his desk. Pasha still had a face like a sulky monkey nesting in a rumple of dark hair, but since the Glow had gone, and with it the ill-gotten pain that powered it, he’d seemed to grow. Less jumpy now, but still plenty angry.

He looked up from the news-sheet he’d been scowling over. “What happened to you? You look like shit.”

He was still a git. I braved the vagaries of my desk drawer. The trick was to open it up, grab what you wanted and get your hand out quick, before it realised what you were doing and slammed shut. It was unreasonably possessive of its contents, I felt, and I only had one good hand left anyway.

I managed to get out the mirror without incurring any broken bones and studied my reflection. Pasha was right: I did look like shit. I would like to point out that the mirror was a new thing and not lurking in my drawer because I’m incredibly vain. Well, I am quite vain, but that’s not why it was there. No, it was there because of the new direction my magic had taken, and because a lot of people thought I was dead and I wanted it to stay that way, or I would be.

I still had a bit of juice left from my earlier hand-mangling so I did the best I could to tidy myself up, rearranging my face back to my more usual disguise. It’s weird seeing someone else’s face in the mirror every day, but better than being dead. I only let the disguise drop when I slept, or when I shaved. Shaving the wrong-shaped face is hard and, I’d discovered, usually ends in blood and swearing.

I couldn’t do anything about the rather spectacular shiner, though. My new skills weren’t up to that yet, in the same way that I couldn’t rearrange my voice, though I was working on it.

Pasha wandered over, sat on the edge of the desk and grinned his monkey grin. I couldn’t help but like him, no matter how hard I tried not to.

“So, who gave you that and why did you let them?”

“She caught me by surprise. I’ve decided to give up women.”

His snorted in disbelief before he closed his eyes and twisted his hands in his lap.

“You can stop that as well. I told you: you don’t read my mind, I won’t permanently rearrange your face.” It came out sharper than I’d intended, mainly because I didn’t want him figuring out just why the lady in question had belted me one. And the lady before that and, come to think of it, the lady before that as well. Let’s just say, saying the wrong name at a delicate moment isn’t a good move and leave it at that. I was definitely swearing off women. Definitely, for sure this time.

The Kiss of Death, Lastri calls me. I never mean to, but I kill any budding relationship stone dead. Usually it was for more varied reasons, granted. Being unable to resist temptation tops the list. Like responsibility, willpower rarely makes it on to my list of good points. Why deny all those women their chance? So many, and all so lovely…

My wandering eyes had stilled for a while, but were back to their old tricks in something like self-defence for my heart, which, if I’m brutally honest, was as mangled as my hand. Playing my old games took my mind off that, meant I didn’t need to think about it, what I’d lost and Pasha had gained.

Pasha took the hint and changed the subject. “So, the boy, you found him? Any joy?”

“Found him, and, yes, he’s a pain-mage all right. Lastri’s feeding him up, I expect. Built like a stick, and he was about to get the crap kicked out of him by a load of Upsiders. Makes me wonder what the little sod’s done.”

Pasha gave me a cryptic look, but the words were pure viciousness. “Was born, perhaps. Had the audacity to come up here when we stopped the Glow and opened the ’Pit. Got the wrong skin tone, the wrong accent, worships the wrong way. Take your pick.”

His tone took me aback–Pasha looked like a monkey that’s lost its nut, but he could be a lion when he wanted to be, and he would always roar in the defence of Downsiders.

I hadn’t meant it that way; it had just come out as part of my sparkling and charming personality because I was pissed at having to use my magic, but I was still getting used to Pasha’s way of looking at things. “I don’t think––”

“No, I’ve noticed.”

I did think then, though. All the insults when I’d worn a Downsider face, the snarls and spits. The rumours of the Upsider gangs stomping lone Downsiders. Pasha still had it, that blue-white tone lurking under dusky skin. Brought up in the ’Pit with no sun, not even the few minutes a day someone Upside managed. You could usually tell a Downsider at a glance, and the accent was what really gave them away. Given that the Ministry would rather they weren’t here, the embarrassment of them even existing when they’d been denied for decades, the chances of them getting a look at the real sun from up in Heights or above was slim. It might take years for that unearthly pallor to go. It might never go.

“You seen this?” Pasha slapped down the news-sheet he’d been reading on my desk. I caught sight of the headline: DOWNSIDERS SPREAD NEW DISEASE. Near the bottom was another article about Downsiders scattering malicious rumours of what had gone on in the ’Pit, and how it wasn’t true, followed by a frankly laughable account of what had “really” happened. Which, naturally, given that this was a shadow–not officially sanctioned, but a mouthpiece for some of their more vocal ministers–Ministry news-sheet, was a load of old bollocks. As was the bit about mages and our unholy ways and it was all our fault. Well, it was mostly untrue. I am fairly unholy. And I had screwed ever. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved