- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

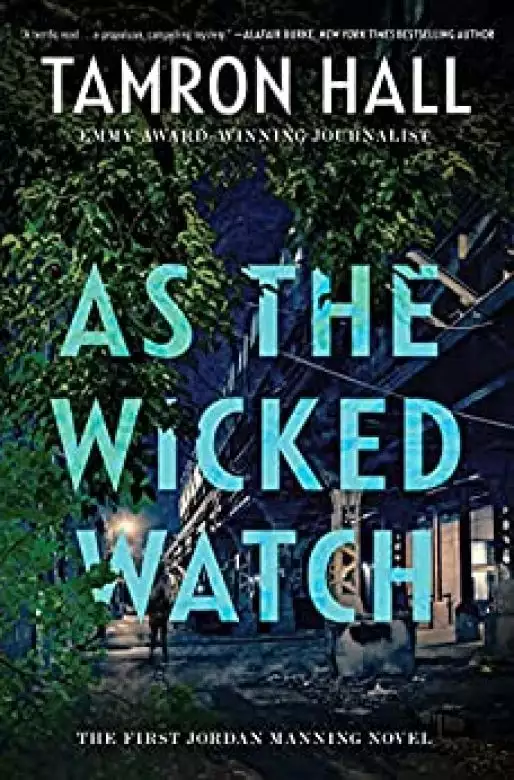

The first in a thrilling new series from Emmy Award-winning TV Host and Journalist Tamron Hall, As The Wicked Watch follows a reporter as she unravels the disturbing mystery around the deaths of two young Black women, the work of a serial killer terrorizing Chicago.

When crime reporter Jordan Manning leaves her hometown in Texas to take a job at a television station in Chicago, she’s one step closer to her dream: a coveted anchor chair on a national network.

Jordan is smart and aggressive, with unabashed star-power, and often the only woman of color in the newsroom. Her signature? Arriving first on the scene—in impractical designer stilettos. Armed with a master’s degree in forensic science and impeccable instincts, Jordan has been able to balance her dueling motivations: breaking every big story—and giving a voice to the voiceless.

From her time in Texas, she’s covered the vilest of human behaviors but nothing has prepared her for Chicago. Jordan is that rare breed of a journalist who can navigate a crime scene as well as she can a newsroom—often noticing what others tend to miss. Again and again, she is called to cover the murders of Black women, many of them sexually assaulted, most brutalized, and all of them quickly forgotten.

All until Masey James—the story that Jordan just can’t shake, despite all efforts. A 15-year-old girl whose body was found in an abandoned lot, Masey has come to represent for Jordan all of the frustration and anger that her job often forces her to repress. Putting the rest of her work and her fraying personal life aside, Jordan does everything she can to give the story the coverage it desperately requires, and that a missing Black child would so rarely get.

There’s a serial killer on the loose, Jordan believes, and he’s hiding in plain sight.

Release date: October 26, 2021

Publisher: William Morrow

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

As the Wicked Watch

Tamron Hall

November 2007

Top-of-the-afternoon broadcast

“Jordan, we’re live in sixty,” said Tracy Klein, my favorite field producer, nudging me to get into place.

“Okay, hang on,” I said, distracted by a rush of butterflies and the sudden urge to pee, which happened every single time I was about to go on the air. I guess it was my body’s way of preparing me for the moment that never got old, but soon panic struck. My earpiece was in, but the anchors’ voices sounded like Charlie Brown’s parents.

“Hey, you guys. I can’t hear. You’re not coming through very clearly. The echo is killing me,” I said.

I looked up.

Please, not today.

In an instant, the sky darkened over historic Bronzeville on Chicago’s South Side, a sign of the dip in temperatures I recalled hearing on this morning’s weather forecast. Chicagoans and people all across this state have to deal with one inescapable fact, and that’s the cold. Sure, I’d heard people who claimed to love the change of seasons. But to a person from Austin, Texas, that sounded like a case of Stockholm syndrome. Or at least that’s what I told my friends from the Midwest when they tried to convince me otherwise.

“Guys, are you trying to blow my ears out?” I shouted at the men a few feet away in the news van. Clearly, whatever they did had fixed the problem. The sound coming out of my earpiece could now be heard in the next county. I stretched as far as my arms could go in this super cute, single-button fitted jacket that looked tailored but wasn’t—I’d bought it off the rack—and turned down the literal voices in my head.

“Tracy, when are we getting new equipment? This earpiece was around when . . .”

“Jordan, focus,” she interrupted. I could tell Tracy wasn’t in the mood for my climbing up on my soapbox today. I glanced down and noticed the heels of my most expensive pair of pumps had slowly disappeared into the soft soil beneath the “L” train track. The low-lying area was prone to flashflooding, and my poor shoes were the latest casualty.

What was I thinking?

“Scott, how’s your sound?”

Scott Newell hoisted the camera off the static tripod and steadied it against his right shoulder. He signaled all good with a left-handed thumbs-up.

So long as Scott’s sound is working, I’ll be okay.

Scott is my steady hand and the antidote to my impulsive nature. My voice of reason out in these streets. The irony of us falling into stereotypical gender roles was particularly strange in a business where independent, successful women still kept secrets about gender bias and sexual harassment while reporting on these very matters. But I guess it didn’t hurt that he had a smile that had melted a few women and, heck, some men, too, when I’d tried to negotiate a longer interview with an unwilling participant.

For that, Scott is my favorite cameraman, but also because he has steady hands and one of the best points of view behind a lens I’ve ever seen. And he’s reliable—probably one of the most reliable men in my life right now, to tell the truth. In television, allies are everything, and for reporters, the natural first ally when you arrive at a new station is the cameraperson. A unique trust developed quickly with long hours on the road, especially on those occasions when we had to chase down some guy accused of foul play in his wife’s disappearance—in my case in heels. You need someone willing to drag you along like those poor women in the campy horror films who’d break a heel and fall just as the killer closed in on them with a chainsaw. Leave no screaming injured woman behind due to her poor choice of footwear. That’s Scott.

“Thirty seconds, Jordan.” The voice in the earpiece had reverted back to a whisper.

“I don’t know what it is, Scott, but my sound is terrible. Can you hear me?”

Scott shrugged his shoulders, not worried that I was seconds from being one of those reporters pressing against their ear, yelling, “Can you repeat the question?”

“Tracy, I still can’t hear you guys.”

“Hold on, Jordan,” Tracy said. “Hold on, we are trying to fix it.”

If the sound issues weren’t enough to make me want to run into the liquor store a few yards away and drown my nerves, the clouds had assumed the starting position and were waiting for a checkered flag. Hanging low and dense like an alien invader, they made Bronzeville appear more sinister than necessary. “Sketchy,” as my mother would say: with vacant lots, boarded-up retail shops and liquor lounges, and potholes the size of a kiddie pool.

The wind gusts this city is famous for sprayed a mix of prickly dirt, gravel, and rock against my bare legs. I could feel a few of the pebbles land inside the arches of my black Stuart Weitzman pumps, a splurge I permitted myself for my twenty-eighth birthday, now likely the dumbest purchase of my life but still one of the cutest. I could hear the words of assistant news editor and my newsroom BFF Ellen Holbrook come back to haunt me.

“I’m just saying, if it were me, I wouldn’t wear my four-hundred-dollar Stuart’s—not today, not where you’re going. Oh, that’s right, I don’t own any,” Ellen quipped, exposing a hint of the East Coast accent she picked up during summers spent with her grandparents in Menemsha, Massachusetts, a small fishing village on Martha’s Vineyard where everybody sounds like a Kennedy.

The wind whipped the air like a strap, and discarded handbills, plastic bags, and food wrappers were violently sucked into the honeycomb cells of the chain link fence surrounding the abandoned playground. Divided between areas for toddlers and for big kids, it was named in honor of Ida B. Wells-Barnett, a Black investigative journalist and a total badass in her day. I wonder if she would have done a show like 60 Minutes or Dateline.

It’s amazing where the mind travels at a crime scene. I’m convinced it’s how the brain copes with the sick reality of what humans are capable of.

The playground was wholly unrecognizable from its condition just a few weeks ago when Scott and I were the first to arrive at the scene. The city has since rid the cracked concrete slab and the adjacent grassy field of trash, dandelions, and what we back in Texas call horseweed or marestail, which grows more than six feet tall. When I was a child, I used to visit my cousins on my mother’s side in Galveston, Texas. A lot of time was spent running in and around the weeds. It was funny how different they looked erupting from the concrete jungle versus the soft soil beneath a Texas sun, as statuesque as pine trees. The bark was so thick that if you cut it, some inexplicable white liquid would’ve probably squirted out. My lack of appreciation for it all was lost in my understanding of why curious prepubescent boys would be drawn to a place that so effectively cloaked their mischief as they pored over their discoveries.

That it once was a children’s play area named after a Black woman who paved the way for people like me to work as investigative journalists only made its fate that much more of a shame.

“Jordan, five! Count it!” the producer yelled.

“Scott, you can hear them. Cue me in,” I instructed. “Just yell, ‘Go!’”

He nodded.

“Okay, Jordan,” Scott said. “The desk is about to hand it offfff!”

He pointed and mouthed Go, as if a Hollywood director had burst onto the scene. His over-the-top cue nearly made me laugh. I took a deep breath, fighting the visual of his absurd gesturing, and refocused on why I was here in the first place.

“Diana, I’m at the Ida B. Wells-Barnett playground at 45th and Calumet in Bronzeville. It’s been weeks since a crew of prisoners from Cook County Jail on cleanup detail made a gruesome discovery here. Now investigators believe they’ve established a connection between the body of an African American woman found behind a dumpster at a popular South Side restaurant last week and the victim found here.”

Other news media had referred to this latest victim as a prostitute. I didn’t have the heart to describe her that way after speaking with her mother. She was somebody’s child. Labels give people a reason not to care when aired out on the news. A murder? Oh, she was just a prostitute. A victim? Police said she was on drugs. As the forty-five-second clip of my prerecorded interview with the victim’s mother played, I thought about her face, hardened by heartbreak long before her daughter was found dead and partially burned outside a dumpster. Trust me, there was no describing the look. You knew it when you saw it watching from your sofa as the local news camera moved in on a heartbroken helpless parent.

“Powerful clip!” chimed in midday anchor Diana Sorano, her genuine enthusiasm making her more audible than I’d anticipated. The wind whipped my hair across my face, and in the moist air, my face morphed from dewy but tolerable into a sweaty mess likely to spark a viewer complaint that I looked too shiny. The first raindrop splashed across my nose. I tried not to frown, but felt my eyebrows furrow, a bad habit.

“Jordan, with yet another murder of a young African American woman, what are some of the community leaders saying? Are they questioning how police are handling these cases?”

Did she lob that question at me to get me to state the obvious? That people had doubts that the police would use all the resources available to draw a connection between these two homicides, if there was one? Or was she oblivious? Of course people were asking that question. Wouldn’t you if you lived here?

“Diana, there is a growing wave of discontent over the number of unsolved murders of Black women on the South and West Sides. Now, with the murder of Tania Mosley, that number stands at eight over the last two years.”

“Thank you, Jordan, and again, I look forward to your special report, which airs tonight during the ten o’clock broadcast, with Tania’s mom.”

I wondered whether Diana fully understood what this latest murder meant. Would she be looking forward to a special report about White girls being killed? My thoughts went dark, realizing my snap judgment was unfair. She wasn’t looking forward to a report on anyone’s being killed, no matter their race. It was just that scripted language trap many anchors tended to fall into after years of seeing the same kind of story over and over again. In a few seconds, this story would vanish and the commercial break would act as a palate cleanser until the next funny video everyone was talking about or the comforting kicker about someone or some company doing a good thing. From confronting you with a murder to making you feel motivated in twenty-five minutes or less.

“She looks like a fighter,” Diana said. “My heart goes out to her. I hope she has someone to lean on for support.”

Yeah, me too. But it won’t be me. Not this time.

It started to rain lightly, but I was frozen in place, eyes locked on the camera as I waited to hear all clear from Scott.

“Okay, we’re out!” Scott shouted. “Let’s go, Jordan. Run!”

Scott broke down his tripod and was halfway to the news truck by the time I pried my shoes out of the mud that now encased them, and the sky burst like a thumped piñata.

October 11, 2007

Scott and I drove up and down Martin Luther King Jr. Drive searching for the perfect spot to set up for the live broadcast. Numerous posters of Masey James’ dimpled face become the morbid bread crumbs leading us to where we want to be. She’d been missing for nearly three weeks, and the posters were a sign of time moving forward with no answers. Some were melted into a blob of ink, her face no longer decipherable or the hotline number half missing, erased by time and weather. The worn posters paled in comparison to the signs of time gone by as we looked around the historic Bronzeville community for a place to park. In the 1930s and ’40s, this community was known as the Black Metropolis, an enclave of upper-middle-class artists and entertainers, business owners and numbers runners. It possessed the same sentimental notes as Harlem in New York, Baldwin Hills in L.A., or Detroit’s Paradise Valley. They were all landmark communities built on black wealth, but the ups and downs of an economy not built on fairness had taken its toll. Today, under a slow boil appreciation, it was slowly gentrifying into something new but remained a crown jewel of a broader South Side community.

Earlier, Scott and I grabbed breakfast downtown before heading south to police headquarters. We didn’t want to be late for my one-on-one interview with Detective Mitch Fawcett. This interview was the talk of the newsroom, and the pressure was on for me to hold his feet to the fire. He had been adamant about not sitting down with me to talk about what he called “the case of a potential runaway.” It was a surprise to everyone on the crime beat that he had his comms team reach out with the stipulation that he wanted to talk with me. Was it because I was the most visible Black woman at the station? I viewed his offer with suspicion. I refuse to be his middleman to get out some generic message to tamp down the anger. The ol’ “We take this seriously and we are working so hard . . . harder than you could even imagine” spiel. Ellen told me I was overreacting.

“Oh, just go for it. Build the relationship. He knows you don’t suffer fools, Jordan.”

“Look, I know Mitch Fawcett. Either he has an agenda or his boss is making him do it. Let’s hope I don’t have to call him out.”

In contrast, his boss, police superintendent Donald Bartlett, was a pure softy, with a mild-mannered demeanor and a strong resemblance to Santa Claus. I struggled to take him seriously and often wondered how he got the job. This was a tough town. Under all that fluff must be a guy you didn’t want to meet in an alley.

Scott and I arrived at Chicago police headquarters a few minutes early. Walking up to the front desk, I felt dwarfed by the massive flags framing the entrance, leading to a well-worn desk. As I approached, it hit me that I hadn’t followed instructions. I was supposed to call Fawcett first to let him know we were parked out front.

Strike one! Great. Now this guy has an opening to scold me before we even get started.

I pulled my phone from my bag and called, realizing that since every camera in the lobby was recording my every move, he probably already knew I was in the building.

“This is Fawcett.”

“Hello, Detective Fawcett. It’s Jordan Manning. We’re here. I mean, we’re in the lobby.”

“Jordan, I told you to call from the parking lot.”

“Sir, I got distracted,” I said, trying to sound apologetic, but the snark came out anyway. “We are here. Should I go back out to the lot and call again?”

And here we go, Jordan!

“Just have a seat in the lobby,” he said. I sensed he was attempting to maintain control.

I can’t seem to get off his shit list. I guess I can expect a few extra parking tickets for the next year.

A uniformed officer who introduced himself as Ramirez met us at the security checkpoint. I felt like the kid picked up last from school after her parents admitted they forgot. Ramirez escorted us past the beat-up front desk to a fortified door leading to a series of cubicles, the detectives’ wing. I caught a few glances on the way to an elevator bank in the middle of the building. As we waited, I glanced at the many photos of officers recognized for outstanding performance on one side, those killed in the line of duty on the other.

“Ma’am, go ahead,” said Officer Ramirez, regaining my attention from the rabbit hole of reading every plaque and framed article on the wall.

“Where are we going?’’ I asked.

“Lockup,” he said with a smirk, proud of himself for injecting humor in what he must have processed as an awkward situation.

“Good,” I replied. “I should feel right at home. I’m sure it’s just like my newsroom.”

Ramirez remained silent after his cop humor fell a tad flat. Scott never said a word.

We got off on the third floor and were directed into a room with double doors already propped open.

“Ma’am. Sir,” Ramirez said, motioning for us to go into a conference room with a long rectangular table and a display of the American flag in one corner and the four-star flag of Chicago in another.

Scott surveyed the room to establish the best camera angle. “Can we dim the fluorescent lights?” Scott asked the officer.

Ramirez was looking up at the lights like he’d never noticed them before when Fawcett entered the room, clutching a notepad against his chest like it was Kevlar body armor.

“Hi, Jordan, thank you for coming,” Fawcett said a little too enthusiastically.

Phony does not suit this guy well. “Sure, Detective. I was surprised to hear from you.”

“Sit down.” He motioned me to the head of the table.

“Have a seat, Jordan,” would have been more appropriate.

The top of his pointy bald head glistened under the lights.

“Actually, Detective, if you could sit there instead, with the four-star flag at your back, and Jordan, you sit here.” Scott pointed. “If we face the other way, we’ll catch shadow from those blinds over there.”

“Sure,” Fawcett said.

“Detective, before we begin, I’d like to establish the focus of this interview,” I said half matter-of-factly, half “don’t try and play me, mister.”

“All right then,” he said. “Shoot.”

“Police have consistently called the disappearance of Masey James a runaway case. Is that changing?”

“We haven’t ruled it out,” he said. “Teens who run away from home can avoid detection for months.”

“But something’s changed. What?” I asked.

“Nothing’s changed, Jordan,” said Fawcett, his fake smile now transformed into a grimace of exasperation. “The young lady doesn’t fit the profile.”

I smile while thinking, You idiot. And you’re just now figuring that out?

From what Masey’s mother, Pamela Alonzo, had shared with me about her daughter, I was confident she was no teenage runaway. She reminded me too much of myself at fifteen—a girlie girl who took pride in her appearance, someone ambitious and sure of herself.

The interview began and ended in a flash. Fawcett’s admission off-camera that Masey didn’t fit the profile of a runaway wouldn’t come so easy on-camera. Typical.

“This is an ongoing investigation, but we’re adding personnel and considering some other potential scenarios,” Fawcett said.

“Can you elaborate?” I asked.

“I’d rather not, but I want to assure the community and all of Chicago that we will exhaust all resources to find Masey,” he said.

So that’s it? You called me here for this? Is this guy kidding me? I can’t take this back to the newsroom.

“Sir, with all due respect, did you lose valuable time dismissing this as a runaway case?” I asked.

“Not at all. We have a protocol and we followed it. But again, let me stress, this is a priority, and we want to assure Masey’s family and all of Chicago we are laser focused on this case and on finding Masey. We are working with the family to trace her every move.”

And there you have it—that’s the agenda. “We are working on it.”

I glared at him with the “That’s it?” look I’d mastered after years of interviewing cops, but he didn’t take the bait and ejected himself from the chair like a fighter pilot getting the hell out of the hot seat.

He didn’t even bother to walk us to the elevator. Where was Ramirez? Were we just supposed to pack up and leave on our own?

Scott looked at me shaking his head, his signature move when he had nothing to say or nothing he thought I wanted to hear. As he packed up his gear, I texted Ellen. What a bust!

She sent a quick reply. What happened?

But I just texted back Talk soon, because frankly reliving any part of what had just taken place was a waste of my time.

As Scott and I exited police headquarters, a familiar face stopped me in my tracks. It was Masey James smiling at me, her image captioned with MISSING in bold black letters tacked to a utility pole.

Perhaps Fawcett should pay more attention to what’s in his own backyard. It says MISSING, not HELP FIND A RUNAWAY.

Someone was sending a message, but it wasn’t getting through. I felt like grabbing the poster and running back inside and slapping it on Fawcett’s desk.

Masey’s mother had publicly rejected police assertions that her daughter had run away from home. But there still hadn’t been an Amber Alert issued by law enforcement, which was what the alert was meant for. This kid was looking at a future where she could write her own ticket. If it wasn’t used in a case involving a teenager any parent would be proud of, then when?

The missing posters were the community’s way of issuing an alert for one of its own. Fawcett might have tricked his mind into believing that police were doing their job, just following protocol. But I couldn’t ignore what I recognized as a plea for help, for the police to care, for attention from the media, and for answers.

Back in the news van, Scott and I headed toward King Drive, and I rolled down the window and tilted my head out and up toward the sky. The sunlight filtered through the trees that stood guard outside of the stately two- and three-flat brownstones—walk-ups, some people call them—that lined both sides of the boulevard. These houses were unlike any I had seen back in Austin, Texas, and portlier than the brownstones in Harlem. I was impressed with the architecture, though, the kind of regal, ornate design work most builders had abandoned years ago for sameness and simplicity.

The tree limbs, heavy with leaves changing into their fall brilliance, cast a shadow like an archipelago upon the ground below. If I was going to do my broadcast from here, the lighting had to be right.

Scott easily found parking on the street. I jumped out of the van and surveyed the sidewalk for rocks and cracks, anything that could trigger a misstep or snag the heel of my pumps during my walk and talk.

“It’s hard to look at these, isn’t it,” Scott said.

“What?” I asked.

“These posters. I mean, what a nightmare for a parent,” Scott said. I couldn’t pretend to completely understand what it was like for Scott, the father of a five-year-old son and an eight-year-old daughter he sees every other weekend and twice during the week since his divorce. “I mean, there’s been no sign of her in three weeks. What are the chances she’s still alive?”

I fought to hold back the answer, forcing the air down required to articulate what I was thinking.

Fawcett’s pronouncements spun around in my head. Finally, police no longer viewed Masey as a potential runaway. Five more detectives had been put on the case. His mission was accomplished. His effortless PR stunt playing out, leaving me feeling like a useful idiot. My mic and camera the tools he needed to make people think it was all okay.

Scott asked again, “Do you think she’s alive? What are the odds, Jordan?”

“Probably not good,” I responded. “Most missing persons cases don’t have happy endings. You heard what Fawcett said. This is a different investigation now. And they’re probably afraid they’re going to catch heat for misclassifying Masey as a runaway for damned near three weeks if she turns up dead.”

While I couldn’t fully wrap my head around what Scott was thinking as a dad, especially the dad of a young girl, I could fully understand the loss and helplessness Masey’s family must be feeling.

Jordan, don’t go there. Get out of your own head.

“Scott, look, Masey had just started attending this awesome STEM school. She dotes on her little brother and her cousin’s baby girl. She shops in her mother’s closet and redoes her nails every other day,” I said, bragging on Masey, a girl I’d never met, like I’d heard her mother do, a feeling of kinship that gave my words a tone of protectiveness.

My best friend in Austin, Lisette Holmes, and I had talked about this.

“Masey sounds like a loving, happy child,” Lisette said. “Not a girl that would just take off like that. Something’s not right.”

I ignored my own warning and went deeper into the dark recesses of my mind. While Scott set up, I told him about a case I’d covered while working at a Dallas station that haunts me to this day.

“Two sisters, six and eight years old, who lived in a small town about an hour from the city were reported missing by their mother, Luella Buford. She told police she last saw them playing in the backyard, which backed up to a wooded area. When I interviewed Luella one-on-one, she told me she’d seen a Black man in a black van circling the area, even driving past her house a couple times the day the girls went missing.”

A Black man in a black van. The color of fear. The descriptor of evil. Was it possible? Of course. Did I doubt her story? Yes, from the very start. The mental gamble it took to look at a presumed victim and see them as the villain was a hard place to be as a reporter. The urge to look them in the eye and flat out call them a liar was a disorienting circumstance to fight.

But the fact she went overboard with black—Black guy, black car, wearing dark clothing—it was something that even now, when I tell people the story, some get it right away. Others, like Scott, struggled to connect the signs and the red flags. I didn’t feel like explaining it to him.

“After about two weeks, their bodies were found in a well on an abandoned property,” I said. “They’d been sexually assaulted.”

“Let me guess. It wasn’t a Black guy,” Scott said, his tone indicating he knew where my story was going.

“Exactly!” I said, pointing my finger like a game show host when a contestant guessed the right answer. “But the mother wasn’t innocent. Luella had a boyfriend named Jerry Branahan. Jerry was well known around the area. A lot of people felt sorry for him because he’d had his struggles, and he was mentally disabled. He wasn’t the girls’ father. Luella met Jerry at a laundromat a year after her breakup with her baby daddy. His $568-a-month disability check was a big help to her. She was a piece of work. She manipulated him to the point that he knew to hand over that check before he could close the mailbox.”

All these years later, I still remember a mundane detail such as the amount of Jerry Branahan’s monthly disability paycheck, but not my own checking account number.

By now, Scott and I, but more important, the news truck had attracted attention, like it was an open invitation for someone to come over and ask, ‘‘What’s going on?’’

“To make a long story short,” I said, “it turned out Jerry had the girls at an abandoned house that was one of his former foster homes. Luella thought she could play on the townspeople’s and her family’s sympathy to extort money. But Jerry, high on glue, ended up raping the girls.”

“Wow, that’s terrible,” Scott said. “I didn’t know glue sniffing was still a thing.”

“It is in rural Texas,” I said. “Oh, oh. We’ve got company.”

The few people who’d gathered moved in closer. I was in no mood for random questions. I was here for answers, but I knew I’d have to help Scott escape the growing crew of folks around him.

“Hi . . . yes . . . we’re about to do a live shot. Do you mind . . . excuse me, do you mind moving back over this way?” Scott asked the gatherers.

Getting out of the van, I realized we were parked a few steps from a Masey missing poster tacked to a tree. For the first time, I looked beyond her striking features, noticing her perfect posture. The poise anyone who had ever taken a school picture understood. It was unnatural and regal at the same time. The photographer hired by the school accepted nothing less than pinpoint precision. Chin up, shoulders back. Smile.

Scott had managed to escape the enquiring minds. Without thinking, I said, “She borrowed that top.”

“How do you know that?” Scott asked.

“Her mother told me,” I said, my eyes still glued to Masey’s smile.

What a beautiful child.

“Really? When did she tell you that?” he asked.

“It’s cathartic, I think,” I said, avoiding Scott’s question. “You know, for her to describe mundane details like that to someone about her daughter. Anything to keep from going totally nuts.”

“So, you’ve spent some time with her?” Scott asked, rephrasing the question.

I wasn’t sure if Scott was probing because he was concerned or if he was just being nosy.

In either case, his questions began to feel like an interrogation. I’m to blame for my paranoia, for letting a potential victim’s relative become a tad too familiar with the lady from the news. How else was I supposed to cover this story if not intimately? With genuine concern?

“Oh, a couple times,” I said, and shrugged my shoulders.

It had been four, in fact, most recently two days ago. The first time was the day after Pamela reported Masey missing. She left a voice-mail message on the station’s tips hotline the morning after her daughter failed to come home. Everybody at the station knows that if it involves missing children, “send them to Jordan.”

My last two years of undergrad at Columbia College in Missouri, I chose a minor in forensic science. Later in graduate school, I wrote my thesis on “Covering Violent Crime: What the Media Misses” to earn my master’s. Though I’m not a native of Chicago, my prior experience on the crime beat in Texas, combined with my forensic education, gave me the street cred to design my own beat.

“I know my baby wouldn’t stay out overnight. I checked every place she could possibly be, and no one has seen her,” Pamela explained in a breathless voice on the tips hotline. “Something’s wrong, and the police won’t help me.”

I realized police were simply following protocol, not to take a missing person’s report until the individual had been unaccounted for for a full forty-eight hours. I called Pam, who told me the police suspected Masey had run off.

“That’s in most cases, they said,” Pam said. “The child has run away and usually comes home or turns up at a relative’s house in a few days. Masey wouldn’t do that. No way!”

Pamela declared emphatically: “Jordan, if the police think I’m not gonna be out here looking for my child, they’re crazy as hell!”

She and I met at a coffee shop not far from the television station by the train tracks on Lake Street. It would become our spot. She shared with me Masey’s excitement over Picture Day and told me that her daughter chose a blouse from her closet. “She’s always in my stuff,” Pam said.

Pamela pulled a wallet size of the image from her billfold. The blouse was a very feminine-looking dark blue and white gingham plaid, with a ruffle down the middle. Masey’s thick, shoulder-length hair spilled over the collar, slightly open at the neck, which revealed a heart-shaped pendant embossed with a rose that fit tightly across her neck. Her bang made a wide left turn like a canopy swooping across her perfectly arched eyebrows. Her hands weren’t visible in the image, but her nails that day were painted a bright pink, aqua green, and periwinkle blue, alternating fingers, Pam told me.

“She loves to make herself up,” said Pam, sitting across from me in the booth during our second meeting at the coffee shop. I hated making her come all the way downtown and felt even worse that she’d ordered and paid for my coffee before I arrived.

“I remembered how you like it, ...

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...