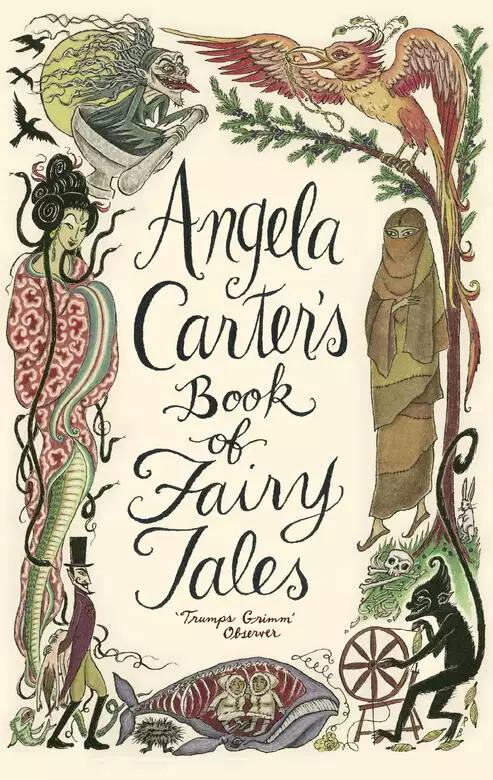

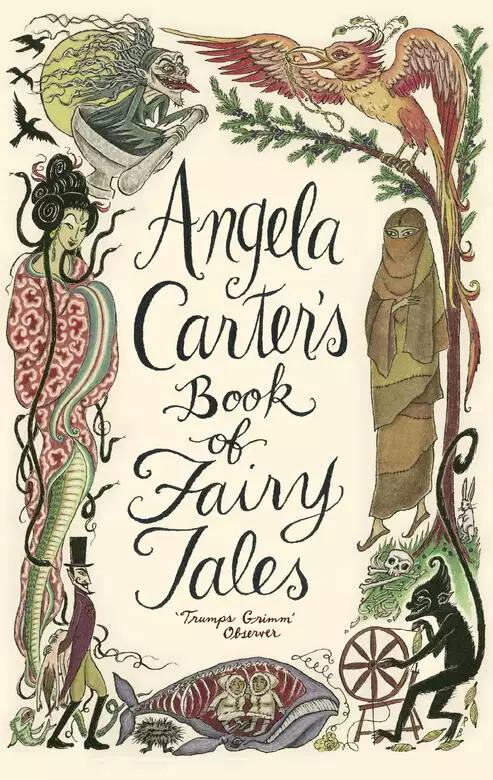

Angela Carter's Book Of Fairy Tales

- eBook

- Hardcover

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

Once upon a time fairy tales weren't meant just for children, and neither is Angela Carter's Book of Fairy Tales. This stunning collection contains lyrical tales, bloody tales and hilariously funny and ripely bawdy stories from countries all around the world- from the Arctic to Asia - and no dippy princesses or soppy fairies. Instead, we have pretty maids and old crones; crafty women and bad girls; enchantresses and midwives; rascal aunts and odd sisters. This fabulous celebration of strong minds, low cunning, black arts and dirty tricks could only have been collected by the unique and much-missed Angela Carter. Illustrated throughout with original woodcuts.

Release date: November 19, 2015

Publisher: Virago

Print pages: 587

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Angela Carter's Book Of Fairy Tales

Angela Carter

Introduction

Sermerssuaq

1. BRAVE, BOLD AND WILFUL

The Search for Luck

Mr Fox

Kakuarshuk

The Promise

Kate Crackernuts

The Fisher-Girl and the Crab

2. CLEVER WOMEN, RESOURCEFUL GIRLS AND DESPERATE STRATAGEMS

Maol a Chliobain

The Wise Little Girl

Blubber Boy

The Girl Who Stayed in the Fork of a Tree

The Princess in the Suit of Leather

The Hare

Mossycoat

Vasilisa the Priest’s Daughter

The Pupil

The Rich Farmer’s Wife

Keep Your Secrets

The Three Measures of Salt

The Resourceful Wife

Aunt Kate’s Goomer-Dust

The Battle of the Birds

Parsley-girl

Clever Gretel

The Furburger

3. SILLIES

A Pottle o’ Brains

Young Man in the Morning

Now I Should Laugh, If I Were Not Dead

The Three Sillies

The Boy Who Had Never Seen Women

The Old Woman Who Lived in a Vinegar Bottle

Tom Tit Tot

The Husband Who Was to Mind the House

4. GOOD GIRLS AND WHERE IT GETS THEM

East o’ the Sun and West o’ the Moon

The Good Girl and the Ornery Girl

The Armless Maiden

5. WITCHES

The Chinese Princess

The Cat-Witch

The Baba Yaga

Mrs Number Three

6. UNHAPPY FAMILIES

The Girl Who Banished Seven Youths

The Market of the Dead

The Woman Who Married Her Son’s Wife

The Little Red Fish and the Clog of Gold

The Wicked Stepmother

Tuglik and Her Granddaughter

The Juniper Tree

Nourie Hadig

Beauty and Pock Face

Old Age

7. MORAL TALES

Little Red Riding Hood

Feet Water

Wives Cure Boastfulness

Tongue Meat

The Woodcutter’s Wealthy Sister

Escaping Slowly

Nature’s Ways

The Two Women Who Found Freedom

How a Husband Weaned His Wife from Fairy Tales

8. STRONG MINDS AND LOW CUNNING

The Twelve Wild Ducks

Old Foster

Šāhīn

The Dog’s Snout People

The Old Woman Against the Stream

The Letter Trick

Rolando and Brunilde

The Greenish Bird

The Crafty Woman

9. UP TO SOMETHING – BLACK ARTS AND DIRTY TRICKS

Pretty Maid Ibronka

Enchanter and Enchantress

The Telltale Lilac Bush

Tatterhood

The Witchball

The Werefox

The Witches’ Piper

Vasilissa the Fair

The Midwife and the Frog

10. BEAUTIFUL PEOPLE

Fair, Brown and Trembling

Diirawic and Her Incestuous Brother

The Mirror

The Frog Maiden

The Sleeping Prince

The Orphan

11. MOTHERS AND DAUGHTERS

Achol and Her Wild Mother

Tunjur, Tunjur

The Little Old Woman with Five Cows

Achol and Her Adoptive Lioness-Mother

12. MARRIED WOMEN

Story of a Bird Woman

Father and Mother Both ‘Fast’

Reason to Beat Your Wife

The Three Lovers

The Seven Leavenings

The Untrue Wife’s Song

The Woman Who Married Her Son

Duang and His Wild Wife

A Stroke of Luck

The Beans in the Quart Jar

13. USEFUL STORIES

A Fable of a Bird and Her Chicks

The Three Aunts

Tale of an Old Woman

The Height of Purple Passion

Salt, Sauce and Spice, Onion Leaves, Pepper and Drippings

Two Sisters and the Boa

Spreading the Fingers

Afterword by Marina Warner

Notes on Parts 1–7 by Angela Carter

Notes on Parts 8–13 by Angela Carter and Shahrukh Husain

Acknowledgements

lthough this is called a book of fairy tales, you will find very few actual fairies within the following pages. Talking beasts, yes; beings that are, to a greater or lesser extent, supernatural; and many sequences of events that bend, somewhat, the laws of physics. But fairies, as such, are thin on the ground, for the term ‘fairy tale’ is a figure of speech and we use it loosely, to describe the great mass of infinitely various narrative that was, once upon a time and still is, sometimes, passed on and disseminated through the world by word of mouth – stories without known originators that can be remade again and again by every person who tells them, the perennially refreshed entertainment of the poor.

Until the middle of the nineteenth century, most poor Europeans were illiterate or semi-literate and most Europeans were poor. As recently as 1931, 20 per cent of Italian adults could neither read nor write; in the South, as many as 40 per cent. The affluence of the West has only recently been acquired. Much of Africa, Latin America and Asia remains poorer than ever, and there are still languages that do not yet exist in any written form or, like Somali, have acquired a written form only in the immediate past. Yet Somali possesses a literature no less glorious for having existed in the memory and the mouth for the greater part of its history, and its translation into written forms will inevitably change the whole nature of that literature, because speaking is public activity and reading is private activity. For most of human history, ‘literature’, both fiction and poetry, has been narrated, not written – heard, not read. So fairy tales, folk tales, stories from the oral tradition, are all of them the most vital connection we have with the imaginations of the ordinary men and women whose labour created our world.

For the last two or three hundred years, fairy stories and folk tales have been recorded for their own sakes, cherished for a wide variety of reasons, from antiquarianism to ideology. Writing them down – and especially printing them – both preserves, and also inexorably changes, these stories. I’ve gathered together some stories from published sources for this book. They are part of a continuity with a past that is in many respects now alien to us, and becoming more so day by day. ‘Drive a horse and plough over the bones of the dead,’ said William Blake. When I was a girl, I thought that everything Blake said was holy, but now I am older and have seen more of life, I treat his aphorisms with the affectionate scepticism appropriate to the exhortations of a man who claimed to have seen a fairy’s funeral. The dead know something we don’t, although they keep it to themselves. As the past becomes more and more unlike the present, and as it recedes even more quickly in developing countries than it does in the advanced, industrialized ones, more and more we need to know who we were in greater and greater detail in order to be able to surmise what we might be.

The history, sociology and psychology transmitted to us by fairy tales is unofficial – they pay even less attention to national and international affairs than do the novels of Jane Austen. They are also anonymous and genderless. We may know the name and gender of the particular individual who tells a particular story, just because the collector noted the name down, but we can never know the name of the person who invented that story in the first place. Ours is a highly individualized culture, with a great faith in the work of art as a unique one-off, and the artist as an original, a godlike and inspired creator of unique one-offs. But fairy tales are not like that, nor are their makers. Who first invented meatballs? In what country? Is there a definitive recipe for potato soup? Think in terms of the domestic arts. ‘This is how I make potato soup.’

The chances are, the story was put together in the form we have it, more or less, out of all sorts of bits of other stories long ago and far away, and has been tinkered with, had bits added to it, lost other bits, got mixed up with other stories, until our informant herself has tailored the story personally, to suit an audience of, say, children, or drunks at a wedding, or bawdy old ladies, or mourners at a wake – or, simply, to suit herself.

I say ‘she’, because there exists a European convention of an archetypal female storyteller, ‘Mother Goose’ in English, ‘Ma Mère l’Oie’ in French, an old woman sitting by the fireside, spinning – literally ‘spinning a yarn’ as she is pictured in one of the first self-conscious collections of European fairy tales, that assembled by Charles Perrault and published in Paris in 1697 under the title Histoires ou contes du temps passé, translated into English in 1729 as Histories or Tales of Past Times. (Even in those days there was already a sense among the educated classes that popular culture belonged to the past – even, perhaps, that it ought to belong to the past, where it posed no threat, and I am saddened to discover that I subscribe to this feeling, too; but this time, it just might be true.)

Obviously, it was Mother Goose who invented all the ‘old wives’ tales’, even if old wives of any sex can participate in this endless recycling process, when anyone can pick up a tale and make it over. Old wives’ tales – that is, worthless stories, untruths, trivial gossip, a derisive label that allots the art of storytelling to women at the exact same time as it takes all value from it.

Nevertheless, it is certainly a characteristic of the fairy tale that it does not strive officiously after the willing suspension of disbelief in the manner of the nineteenth-century novel. ‘In most languages, the word “tale” is a synonym for “lie” or “falsehood”,’ according to Vladimir Propp. ‘“The tale is over; I can’t lie any more” – thus do Russian narrators conclude their stories.’

Other storytellers are less emphatic. The English gypsy who narrated ‘Mossycoat’ said he’d played the fiddle at Mossycoat’s son’s twenty-first birthday party. But this is not the creation of verisimilitude in the same way that George Eliot does it; it is a verbal flourish, a formula. Every person who tells that story probably added exactly the same little touch. At the end of ‘The Armless Maiden’ the narrator says: ‘I was there and drank mead and wine; it ran down my mustache, but did not go into my mouth.’ Very likely.

Although the content of the fairy tale may record the real lives of the anonymous poor with sometimes uncomfortable fidelity – the poverty, the hunger, the shaky family relationships, the all-pervasive cruelty and also, sometimes, the good humour, the vigour, the straightforward consolations of a warm fire and a full belly – the form of the fairy tale is not usually constructed so as to invite the audience to share a sense of lived experience. The ‘old wives’ tale’ positively parades its lack of verisimilitude. ‘There was and there was not, there was a boy,’ is one of the formulaic beginnings favoured by Armenian storytellers. The Armenian variant of the enigmatic ‘Once upon a time’ of the English and French fairy tale is both utterly precise and absolutely mysterious: ‘There was a time and no time . . .’

When we hear the formula ‘Once upon a time’, or any of its variants, we know in advance that what we are about to hear isn’t going to pretend to be true. Mother Goose may tell lies, but she isn’t going to deceive you in that way. She is going to entertain you, to help you pass the time pleasurably, one of the most ancient and honourable functions of art. At the end of the story, the Armenian storyteller says: ‘From the sky fell three apples, one to me, one to the storyteller, and one to the person who entertained you.’ Fairy tales are dedicated to the pleasure principle, although since there is no such thing as pure pleasure, there is always more going on than meets the eye.

We say to fibbing children: ‘Don’t tell fairy tales!’ Yet children’s fibs, like old wives’ tales, tend to be over-generous with the truth rather than economical with it. Often, as with the untruths of children, we are invited to admire invention for its own sake. ‘Chance is the mother of invention,’ observed Lawrence Millman in the Arctic, surveying a roistering narrative inventiveness. ‘Invention’, he adds, ‘is also the mother of invention.’

These stories are continually surprising:

So one woman after another straightway brought forth her child.

Soon there was a whole row of them.

Then the whole band departed, making a confused noise. When the girl saw that, she said: ‘There is no joke about it now.

There comes a red army with the umbilical cords still hanging on.’

Like that.

‘“Little lady, little lady,” said the boys, “little Alexandra, listen to the watch, tick tick tick: mother in the room all decked in gold.”’

And that.

‘The wind blew high, my heart did ache,

To see the hole the fox did make.’

And that.

This is a collection of old wives’ tales, put together with the intention of giving pleasure, and with a good deal of pleasure on my own part. These stories have only one thing in common – they all centre around a female protagonist; be she clever, or brave, or good, or silly, or cruel, or sinister, or awesomely unfortunate, she is centre stage, as large as life – sometimes, like Sermerssuaq, larger.

Considering that, numerically, women have always existed in this world in at least as great numbers as men and bear at least an equal part in the transmission of oral culture, they occupy centre stage less often than you might think. Questions of the class and gender of the collector occur here; expectations, embarrassment, the desire to please. Even so, when women tell stories they do not always feel impelled to make themselves heroines and are also perfectly capable of telling tales that are downright unsisterly in their attitudes – for example, the little story about the old lady and the indifferent young man. The conspicuously vigorous heroines Lawrence Millman discovered in the Arctic are described by men as often as they are by women and their aggression, authority and sexual assertiveness probably have societal origins rather than the desire of an Arctic Mother Goose to give assertive role models.

Susie Hoogasian-Villa noted with surprise how her women informants among the Armenian community in Detroit, Michigan, USA, told stories about themselves that ‘poke fun at women as being ridiculous and second-best’. These women originally came from resolutely patriarchal village communities and inevitably absorbed and recapitulated the values of those communities, where a new bride ‘could speak to no one except the children in the absence of the men and elder women. She could speak to her husband in privacy.’ Only the most profound social changes could alter the relations in these communities, and the stories women told could not in any way materially alter their conditions.

But one story in this book, ‘How a Husband Weaned His Wife from Fairy Tales’, shows just how much fairy stories could change a woman’s desires, and how much a man might fear that change, would go to any lengths to keep her from pleasure, as if pleasure itself threatened his authority.

Which, of course, it did.

It still does.

The stories here come from Europe, Scandinavia, the Caribbean, the USA, the Arctic, Africa, the Middle East and Asia; the collection has been consciously modelled on those anthologies compiled by Andrew Lang at the turn of the century that once gave me so much joy – the Red, Blue, Violet, Green, Olive Fairy Books, and so on, through the spectrum, collections of tales from many lands.

I haven’t put this collection together from such heterogeneous sources to show that we are all sisters under the skin, part of the same human family in spite of a few superficial differences. I don’t believe that, anyway. Sisters under the skin we might be, but that doesn’t mean we’ve got much in common. (See Part Six, ‘Unhappy Families’.) Rather, I wanted to demonstrate the extraordinary richness and diversity of responses to the same common predicament – being alive – and the richness and diversity with which femininity, in practice, is represented in ‘unofficial’ culture: its strategies, its plots, its hard work.

Most of the stories here do not exist in only the one form but in many different versions, and different societies procure different meanings for what is essentially the same narrative. The fairy-tale wedding has a different significance in a polygamous society than it does in a monogamous one. Even a change of narrator can effect a transformation of meaning. The story ‘The Furburger’ was originally told by a twenty-nine-year-old Boy Scout executive to another young man; I haven’t changed one single word, but its whole meaning is altered now that I am telling it to you.

The stories have seeded themselves all round the world, not because we all share the same imagination and experience but because stories are portable, part of the invisible luggage people take with them when they leave home. The Armenian story ‘Nourie Hadig’, with its resemblance to the ‘Snow White’ made famous via the Brothers Grimm and Walt Disney, was collected in Detroit, not far from the townships where Richard M. Dorson took down stories from African Americans that fuse African and European elements to make something new. Yet one of these stories, ‘The Cat-Witch’, has been current in Europe at least since the werewolf trials in France in the sixteenth century. But context changes everything; ‘The Cat-Witch’ acquires a whole new set of resonances in the context of slavery.

Village girls took stories to the city, to swap during endless kitchen chores or to entertain other people’s children. Invading armies took storytellers home with them. Since the introduction of cheap printing processes in the seventeenth century, stories have moved in and out of the printed word. My grandmother told me the version of ‘Red Riding Hood’ she had from her own mother, and it followed almost word for word the text first printed in this country in 1729. The informants of the Brothers Grimm in Germany in the early nineteenth century often quoted Perrault’s stories to them – to the irritation of the Grimms, since they were in pursuit of the authentic German Geist.

But there is a very specific selectivity at work. Some stories – ghost stories, funny stories, stories that already exist as folk tales – move through print into memory and speech. But although the novels of Dickens and other nineteenth-century bourgeois writers might be read aloud, as the novels of Gabriel Garcia Marquez are read aloud in Latin American villages today, stories about David Copperfield and Oliver Twist did not take on an independent life and survive as fairy tales – unless, as Mao Zedong said about the effects of the French Revolution, it is too soon to tell.

Although it is impossible to ascribe an original home for any individual story and the basic plot elements of the story we know as ‘Cinderella’ occur everywhere from China to Northern England (look at ‘Beauty and Pock Face’, then at ‘Mossycoat’), the great impulse towards collecting oral material in the nineteenth century came out of the growth of nationalism and the concept of the nation-state with its own, exclusive culture; with its exclusive affinity to the people who dwelt therein. The word ‘folklore’ itself was not coined until 1846, when William J. Thomas invented the ‘good Saxon compound’ to replace imprecise and vague terms such as ‘popular literature’ and ‘popular antiquities’, and to do so without benefit of alien Greek or Latin roots. (Throughout the nineteenth century, the English believed themselves to be closer in spirit and racial identity to the Teutonic tribes of the North than to the swarthy Mediterranean types that started at Dunkirk; this conveniently left the Scots, the Welsh and the Irish out of the picture, too.)

Jacob Ludwig Grimm and his brother, Wilhelm Carl, philologists, antiquarians, medievalists, sought to establish the cultural unity of the German people via its common traditions and language; their ‘Household Tales’ became the second most popular and widely circulated book in Germany for over a century, dominated only by the Bible. Their work in collecting fairy tales was part of the nineteenth-century struggle for German unification, which didn’t happen until 1871. Their project, which involved a certain degree of editorial censorship, envisaged popular culture as an untapped source of imaginative energy for the bourgeoisie; ‘they [the Grimms] wanted the rich cultural tradition of the common people to be used and accepted by the rising middle class,’ says Jack Zipes.

At roughly the same time, and inspired by the Grimms, Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe were collecting stories in Norway, publishing in 1841 a collection that ‘helped free the Norwegian language from its Danish bondage, while forming and popularizing in literature the speech of the common people’, according to John Gade. In the mid nineteenth century, J.F. Campbell went to the Highlands of Scotland to note down and preserve ancient stories in Scots Gaelic before the encroaching tide of the English language swept them away.

The events leading up to the Irish Revolution in 1916 precipitated a surge of passionate enthusiasm for native Irish poetry, music and story, leading eventually to the official adoption of Irish as the national language. (W.B. Yeats compiled a famous anthology of Irish fairy tales.) This process continues; there is at present a lively folklore department at the University of Bir Zeit: ‘Interest in preserving the local culture is particularly strong on the West Bank as the status of Palestine continues to be the subject of international deliberation and the identity of a separate Palestinian Arab people is called into question,’ says Inea Bushnaq.

That I and many other women should go looking through the books for fairy-tale heroines is a version of the same process – a wish to validate my claim to a fair share of the future by staking my claim to my share of the past.

Yet the tales themselves, evidence of the native genius of the people though they be, are not evidence of the genius of any one particular people over any other, nor of any one particular person; and though the stories in this book were, almost all of them, noted down from living mouths, collectors themselves can rarely refrain from tinkering with them, editing, collating, putting two texts together to make a better one. J.F. Campbell noted down in Scots Gaelic and translated verbatim; he believed that to tinker with the stories was, as he said, like putting tinsel on a dinosaur. But since the material is in the common domain, most collectors – and especially editors – cannot keep their hands off it.

Removing ‘coarse’ expressions was a common nineteenth-century pastime, part of the project of turning the universal entertainment of the poor into the refined pastime of the middle classes, and especially of the middle-class nursery. The excision of references to sexual and excremental functions, the toning down of sexual situations and the reluctance to include ‘indelicate’ material – that is, dirty jokes – helped to denaturize the fairy tale and, indeed, helped to denaturize its vision of everyday life.

Of course, questions not only of class, gender, but of personality entered into this from the start of the whole business of collecting. The ebullient and egalitarian Vance Randolph was abundantly entertained with ‘indelicate’ material in the heart of the Bible Belt of Arkansas and Missouri, often by women. It is difficult to imagine the scholarly and austere Grimm brothers establishing a similar rapport with their informants – or, indeed, wishing to do so.

Nevertheless, it is ironic that the fairy tale, if defined as orally transmitted narrative with a relaxed attitude to the reality principle and plots constantly refurbished in the retelling, has survived into the twentieth century in its most vigorous form as the dirty joke and, as such, shows every sign of continuing to flourish in an unofficial capacity on the margins of the twenty-first-century world of mass, universal communication and twenty-four-hour public entertainment.

I’ve tried, as far as possible, to avoid stories that have been conspicuously ‘improved’ by collectors, or rendered ‘literary’, and I haven’t rewritten any myself, however great the temptation, or collated two versions, or even cut anything, because I wanted to keep a sense of many different voices. Of course, the personality of the collector, or of the translator, is bound to obtrude itself, often in unconscious ways; and the personality of the editor, too. The question of forgery also raises its head; a cuckoo in the nest, a story an editor, collector, or japester has made up from scratch according to folkloric formulae and inserted in a collection of traditional stories, perhaps in the pious hope that the story will escape from the cage of the text and live out an independent life of its own among the people. Or perhaps for some other reason. If I have inadvertently picked up any authored stories of this kind, may they fly away as freely as the bird at the end of ‘The Wise Little Girl’.

This selection has also been mainly confined to material available in English, due to my shortcomings as a linguist. This exercises its own form of cultural imperialism upon the collection.

On the surface, these stories tend to perform a normative function – to reinforce the ties that bind people together, rather than to question them. Life on the economic edge is sufficiently precarious without continual existential struggle. But the qualities these stories recommend for the survival and prosperity of women are never those of passive subordination. Women are required to do the thinking in a family (see ‘A Pottle o’ Brains’) and to undertake epic journeys (‘East o’ the Sun and West o’ the Moon’). Please refer to the entire section titled: ‘Clever Women, Resourceful Girls and Desperate Stratagems’ to see how women contrived to get their own way.

Nevertheless, the solution adopted in ‘The Two Women Who Found Freedom’ is rare; most fairy tales and folk tales are structured around the relations between men and women, whether in terms of magical romance or of coarse domestic realism. The common, unspoken goal is fertility and continuance. In the context of societies from which most of these stories spring, their goal is not a conservative one but a Utopian one, indeed a form of heroic optimism – as if to say, one day, we might be happy, even if it won’t last.

But if many stories end with a wedding, don’t forget how many of them start with a death – of a father, or a mother, or both; events that plunge the survivors directly into catastrophe. The stories in Part Six, ‘Unhappy Families’, strike directly at the heart of human experience. Family life, in the traditional tale, no matter whence its provenance, is never more than one step away from disaster.

Fairy-tale families are, in the main, dysfunctional units in which parents and step-parents are neglectful to the point of murder and sibling rivalry to the point of murder is the norm. A profile of the typical European fairy-tale family reads like that of a ‘family at risk’ in a present-day inner-city social worker’s casebook, and the African and Asian families represented here offer evidence that even widely different types of family structures still create unforgivable crimes between human beings too close together. And death causes more distress in a family than divorce.

The ever-recurring figure of the stepmother indicates how the households depicted in these stories are likely to be subject to enormous internal changes and reversals of role. Yet however ubiquitous the stepmother in times when the maternal mortality rates were high and a child might live with two, three or even more stepmothers before she herself embarked on the perilous career of motherhood, the ‘cruelty’ and indifference almost universally ascribed to her may also reflect our own ambivalences towards our natural mothers. Note that in ‘Nourie Hadig’ it is the child’s real mother who desires her death.

For women, the ritual marriage at the story’s ending may be no more than the prelude to the haunting dilemma in which the mother of the Grimms’ Snow White found herself – she longed with all her heart for a child ‘as white as snow, as red as blood, as black as ebony’, and died when that child was born, as if the price of the daughter were the life of the mother. When we hear a story, we bring all our own experience to that story: ‘They all lived happy and died happy, and never drank out of a dry cappy’, says the ending of ‘Kate Crackernuts’. Cross fingers, touch wood. The Arabian stories from Inea Bushnaq’s anthology conclude with a stately dignity that undercuts the whole notion of a happy ending: ‘. . . they lived in happiness and contentment until death, the parter of the truest lovers, divided them’ (‘The Princess in the Suit of Leather’).

‘They’ in the above story were a princess and a prince. Why does royalty feature so prominently in the recreational fiction of the ordinary people? For the same reason that the British royal family features so prominently in the pages of the tabloid press, I suppose – glamour. Kings and queens are always rich beyond imagining, princes handsome beyond belief, princesses lovely beyond words – yet they may live in a semi-detached palace, all the same, suggesting that the storyteller was not over-familiar with the lifestyle of real royalty. ‘The palace had many rooms and one king occupied one half of it and the other the other half,’ according to a Greek story not printed here. In ‘The Three Measures of Salt’, the narrator states grandly: ‘in those days everyone was a king’.

Susie Hoogasian-Villa, whose stories came from Armenian immigrants in a heavily industrialized part of the (republican) USA, puts fairy-tale royalty into perspective: ‘Frequently kings are only head men of their villages; princesses do the menial work.’ Juleidah, the princess in the suit of leather, can bake a cake and clean a kitchen with democr

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...