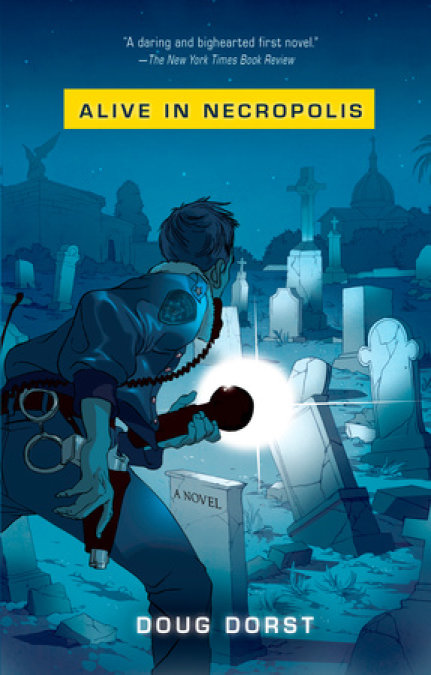

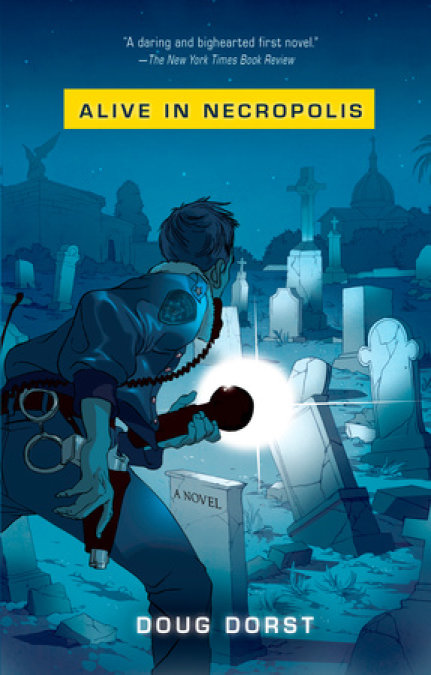

Alive in Necropolis

- eBook

- Paperback

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

A "dark and funny debut"(Seattle-Times) about a young police officer struggling to maintain a sense of reality in a town where the dead outnumber the living.

Colma, California, the "cemetery city" serving San Francisco, is the resting place of the likes of Joe DiMaggio, Wyatt Earp, and William Randolph Hearst. It is also the home of Michael Mercer, a by-the-book rookie cop struggling to settle comfortably into adult life. Instead, he becomes obsessed with the mysterious fate of his predecessor, Sergeant Wes Featherstone, who spent his last years policing the dead as well as the living. As Mercer attempts to navigate the drama of his own daily life, his own grip on reality starts to slip-either that, or Colma's more famous residents are not resting in peace as they should be.

Release date: July 17, 2008

Publisher: Riverhead Books

Print pages: 448

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Alive in Necropolis

Doug Dorst

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

Dedication

PART ONE - BOY THIRTEEN

ONE - FERN GROTTO

TWO - GO WEST

THREE - GOOD SHEPHERD

FOUR - THE WILLOWS

FIVE - JUDE, AWAKE

SIX - THE NEPTUNE SOCIETY

SEVEN - THE GREAT THING ABOUT ALMOST DYING

EIGHT - VAPOR TRAILS

NINE - A DEAD MAN’S BARTHROBE

TEN - THE CHILDREN’S SECTION

ELEVEN - NIGHTWALKING (I)

TWELVE - THE UGLIEST GODDAMN FISH IN THE WORLD

THIRTEEN - HARD TEN ON THE HOP

FOURTEEN - DEATH’S DOOR (I)

FIFTTEN - DEATH’S DOOR (II)

Part two - DIE LIKE AN AVIATOR

SIXTEEN - HAVE YOU SEEN ME?

SEVENTEEN - SMYTHED

EIGHTEEN - NIGHTWALKING (II)

NINETEEN - THE REDEMPTION EXPRESS (1)

TWENTY - MERCER AWAKE

TWENTY-ONE - THE DEAL BUG

TWENTY-TWO - THE NEPTUNE SOCIETY (II)

TWENTY-THREE - THE SWEET FREE FALL OUT OF TIME

TWENTY-FOUR - IT’S GREAT TO BE ALIVE INCOLMA!

TWENTY-FIVE - THE REDEMPTION EXPRESS (II)

TWENTY-SIX - GERAMD XAVIER FAHEY B. DECEMBER 1937 D. MARCH 2005 D. MAY 2005

TWENTY-SEVEN - A TIME TO PLUCK UP

Acknowledgements

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

RIVERHEAD books

a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. New York

RIVERHEAD BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA . Penguin Group (Canada),

90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada (a division of Pearson Canada

Inc.) . Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England . Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green,

Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) . Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road,

Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) . Penguin Books

India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi-110 017, India . Penguin Group (NZ),

67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) .

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or

electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted

materials in violation of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

Published simultaneously in Canada

The newspaper article quoted on p. 272, with some omissions and minor additions, is found in

Lincoln Beachey: The Man Who Owned the Sky, by Frank Marrero (Scottwall, 1997).

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Dorst, Doug.

Alive in Necropolis / Doug Dorst.

p. cm.

eISBN : 978-1-101-01494-3

1. Police—California, Northern—Fiction. 2. California, Northern—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3604.O78A

813’.6—dc22

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers and Internet addresses at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

In addition to the above disclaimer, I would like to stress that I do not intend any elements of this narrative to reflect poorly on the real-life Colma Police, who were friendly, informative, accommodating, and unfailingly professional.

Please note that I have taken liberties with history and geography whenever it suited my purposes. This is because I am neither a historian nor a cartographer but a fiction writer, and I like making stuff up.

FOR DEBRA

How does one kill fear, I wonder? How do you shoot a spectre through the heart, slash off its spectral head, take it by its spectral throat?

—Joseph Conrad, Lord Jim

PROLOGUE

A rare sunny morning comes to Colma.

The sky brightens over San Bruno Mountain, bruised blues giving way to baby-cheek pinks and teases of gold. Navigation lights blink, red and resolute, atop the radio towers that scar the broad, rambling summit. Sunlight creeps across the green valley in which Colma is nestled, wicking away the dew from the lawns of the city’s residents.

Twelve hundred of these residents are alive. They do what living people do: work jobs, sweat on treadmills, make love, incur debt, celebrate birthdays, worry about aging, watch prime-time TV, pray, complain about the weather. Another two million of these residents are already dead. No one knows for sure what they do—if they do anything but lie mute, immobile, decaying—but some of the living have their suspicions.

As the sun makes its way across the valley, it shines first on the Cypress Golf Course. Underneath these seventeen acres of Bermuda grass and fescue is the potter’s field where the beggars of cobblestoned San Francisco were buried in numbered graves and forgotten. Four golfers in primary-colored windbreakers take practice swings on the first tee, whipping metal-gleam arcs through the crisp morning air. A greenskeeper backs a long-bed golf cart out of the maintenance shed, and a lone golden-crowned sparrow answers the cart’s reverse-warning beeps with a plaintive, unrequited song.

The first golfer tees up his ball and takes his stance with the light morning wind luffing his nylon sleeves. As he swings, his plastic spikes slip in the wet tee box, and he slices the ball dead right, a line drive into the pine trees and scrub. He mutters a curse, blaming himself for his first-tee jitters, but then the ball thwocks against something in the woods and caroms out, skidding ahead on the slick grass and rolling to a stop in the center of the fairway, just a choked-down 8-iron away from the green. He turns and grins as his friends moan their disbelief. Lucky sonofabitch. Somebody’s looking out for you today. And they continue their round: nine holes, played twice. It never occurs to him that the brownish scuff on his ball did not come from a tree or a rock or a log, but from a misshapen human skull coughed up by the shifting earth of the fault-lined valley.

The glow of morning spreads over the easternmost cemeteries of Colma: Olivet Memorial Park; the Serbian Cemetery; Pet’s Rest; and the two Chinese cemeteries, Hoy Sun Memorial and Golden Hills.

Across Hillside Boulevard.

Nocturnal gamblers emerge from the front doors of the Lucky Chances 24-Hour card house, slack and pale as fish in a bucket; they rub their eyes in the morning light, then collapse into their cars and drive away. All of them—the winners, the losers, the breakers-even—will be gnawed at by the if onlys until the next time they rest their elbows on the soft green baize and ante up.

The day advances into Holy Cross Cemetery, Colma’s oldest, a former potato field blessed in 1892 as a Catholic cemetery to serve San Francisco. Sky-rocketing land values had convinced city dwellers that death was best dealt with elsewhere, and it was roundly agreed that a ten-mile trip southward was not an onerous journey for the dead to make—a mere step or two, in fact, compared to the great voyages on which their souls had already embarked.

The sun rises higher. Cypress Lawn East. Hills of Eternity. Eternal Home. Home of Peace. Salem Cemetery. The Italian Cemetery. The Japanese Benevolent Society Cemetery.

Lawn mowers sputter and cough out puffs of blue exhaust, then rumble to life and prowl the gentle slopes of the graveyards. In the lots of the car dealerships that clot Serramonte Boulevard, beads of dew glimmer on the polished hoods and roofs and trunks, while strings of red, white, and blue plastic pennants flick in the breeze, hopeful as America.

Across El Camino Real.

The overnight clerk at the Zes-T-Mart prepares to go home. He is a heavily tattooed young man whose pierced ear and nose are connected by a length of steel chain, and he wears the afternoon-shift girl’s name tag because he likes to head-fuck naive customers into wondering if his name really might be Mindy. He notices that, once again, several cartons of Chesterfields have vanished on his watch. He blames their disappearance on ghosts. He will never inform his manager of his suspicions, and he will never ask to see the surveillance tape to test his theory. This coming afternoon, though, he will crawl out of bed and join his four roommates around the house bong (a complicated maze of Habitrail tubes that once housed a gerbil named Happy), and, while watching smoke plumes rise from the mouthpiece, he will dreamily remark, “Dudes. When we die, we’ll all smoke Chesterfields.” And although his friends will burst out laughing, thinking it’s just stony talk, he’ll find himself happy to believe in ghosts who jones for nicotine and remain brand-loyal. It’s the one belief he has that is unique and private, and thus absolutely unassailable.

The sun.

Across Cypress Lawn West, the Greek Orthodox Cemetery, Greenlawn Memorial Park, and, finally, Woodlawn Memorial Park.

The day rolls by, and one hundred twenty-two people are interred in Colma, this self-described “city-cemetery complex.” Mourners lift their eyes skyward as jets taking off from SFO thunder overhead, drowning out somber-voiced pieties and whispered farewells. Solitary and rickety white-haired people struggle up the muddy incline at Pet’s Rest to lay wreaths for departed cats, dogs, bunnies, goats, horses, ocelots. Four mortuaries, ten florists, and eight monument carvers within the city limits are open for business, ensuring that the dead are admirably furnished. One proprietor reminds a new employee to speak slowly and with pleasant, reassuring words when asking for customers’ credit cards, and instructs her to up-sell only the lost, the desperate, the bewildered, the afraid, the stoic, the defeated, and the accepting. “Never the angry,” he says. “It’s best to avoid a scene.”

At the end of the day, the fog sweeps into Colma, a cold Pacific breath that flumes over the coastal hills. It hunkers down for the night, thick and mist-filled, alive with visible eddies and chutes that are swept by the chilled wind. Night-shift police officers reporting to the station zip their Tuffy jackets against the cold and pin their badges to the outside. Through the night, they patrol the quiet streets, wait for intoxicated drivers leaving Molloy’s to cross the center line on Old Mission Road. They intervene in a domestic dispute on Spindrift Lane, thwart lumber thieves loading a pickup behind the home-improvement warehouse, break up a fight at the movie theater. They run passing checks through the cemeteries and sweep their spotlights over the fields of granite and marble, chasing away copulating kids, who dart like sprites into the shadows behind mausoleums and obelisks and weeping angels, struggling to hitch up their pants or just running bare-assed with their bundled clothes in their arms and their exposed skin shining ghost-white.

The next morning, one of these officers—Wesley Featherstone, a twenty-seven-year veteran—will not report back to the station. His Crown Victoria will be parked underneath the grand stone archway that leads into Cypress Lawn East, the driver’s door ajar and the alert tone pinging softly. Sergeant Featherstone will be slumped behind the wheel of the cruiser, one hand reaching toward the radio, the other clamped over his mouth. His eyes will be wide and panicked. A lock of his thin hair—once red, long since turned peachy gray—will dangle from his temple, hanging all the way to his chin.

Featherstone will be dead of cardiac arrest.

Four dead men will sit atop the archway and pass a jug of daisy-petal pruno to toast their success. One of them will take a deep swig, dribbling onto his powder-blue tuxedo jacket, then hand the bottle to a hard-looking man with bloody fingertips, who will push him off their perch. The man in the tux will slam facedown on the pavement, inches away from the cruiser’s front bumper. He will yelp and howl and curse the persistence of gravity even as his shattered bones begin knitting themselves together again, as ghost bones do. The rest of the gang will shinny down to the ground, and all four of them, laughing and swaying drunkenly, will gather around the car for a final round of taunting the sergeant’s corpse. Then they will stagger off to catch some rest. Even the dead need a little shut-eye sometimes.

A twenty-year-old Salvadoran landscaper reporting early for his first day on the job will hop out of a pickup truck, slap a good-bye on the quarterpanel, and wave as his cousin drives away. As he passes under the archway, he will glance into the cruiser’s windshield and discover the corpse. This will be his first up-close glimpse of death, of an empty, defeated body, and as soon as he is able to unlock his legs, he will sprint down El Camino, get on the first bus he sees, and head out of town, anywhere, he won’t care. He will stare vacantly out a knife-scratched window as the bus rumbles through the foggy morning. The young man’s name is Ángel María de Todos los Santos, and he will forever be haunted by the pop-eyed look of terror on Featherstone’s face. He will come to dread the hour of his own death even more acutely, forever robbed of the ability to believe that God helps souls pass gently. He will not appear in this story again.

PART ONE

BOY THIRTEEN

ONE

FERN GROTTO

It is a rainy night, eight months after Wesley Featherstone’s life of devoted public service was honored with moist eyes, a dolorous wheeze of bagpipes, platters of cocktail franks and baked ziti, and, finally, a blast of crematory flame. Officer Michael Mercer, Colma Badge Thirteen, steers his cruiser through that same archway at Cypress Lawn, only dimly aware of how desperately he wants to be a hero, and not at all aware that he is about to become one.

Mercer is driving one of the department’s new Crown Victorias. The vehicle in which Featherstone died is gone, auctioned off, parked in a citizen’s garage somewhere down the peninsula. No one wants to patrol in a dead man’s cruiser. Fortunately, the Colma P.D. is well-enough funded that no one has to.

Mercer snaps on the cruiser’s alley lights. The rain-glazed grass glows an unearthly green in the halogen beams. Daisies shine blue-white and astral, scattered points of lonely, unconstellated light. Officer Nick Toronto, riding shotgun, radios their position, and they drive slowly through the cemetery, lighting up the night around them as they follow the looping pathways. Mercer, as always, is on the lookout for trouble, but all he sees is ordinary graveyard detritus: empty beer cans, tipped-over pots of withering poinsettias, an old boot with its sole yawning away from the upper, wet fast-food wrappers clinging to the stone of a family called Oyster. Mercer usually patrols solo, but Toronto is in charge tonight because Sergeant Mazzarella went home early with a case of the almighty shits, and Toronto assigned himself to ride with Mercer so he can relax, shoot the breeze, keep his mind off his hangover and his nicotine-starved nerves. Mercer doesn’t mind the company, even though Toronto, who’d been his Field Training Officer, still makes him nervous and self-conscious.

“Close your window,” Toronto says. “It’s fucking raw out.”

Mercer shakes his head no, even though he’s cold, too. An Alaskan front is sweeping down the coast of California, and the temperature has plummeted in the hours since midnight. The weather report says steady rain and piercing winds throughout the Bay Area for the next three days. Right now, there are flurries over Twin Peaks, and an inch of snow has accumulated on top of Mount Diablo. The power company has imposed rolling blackouts because they say the grid is sputtering, overtaxed by all the switched-on heaters.

“As the ranking officer in this car,” Toronto says, “I order you to close your window.”

“Sorry,” Mercer says.

“Don’t be sorry. Just close it.”

“Book says open.”

“The Book doesn’t take into account that I’m freezing my nuggets off.”

“Book says open,” Mercer says again. Toronto might be testing him, and Mercer is determined not to screw anything up. The Book, Mercer knows, is the safe way to go. The Book is The Book for a reason.

As they roll through the cemetery, they pass ornate Victorian mausoleums that are more spacious than Mercer’s apartment, the opulent resting places of James Flood, one of the Comstock silver kings, and Claus Spreckels, the sugar baron. They pass the Hearst family and Lillie Hitchcock Coit. The quiet is disturbed only by the patter of rain, the sticky hiss of tires on wet pavement, the Crown Vic’s eight-cylinder grumble, and also Toronto, who keeps on bitching about the cold and tapping an unlit cigarette nervously against the dashboard. He quit smoking three days ago to placate his girlfriend, but Mercer doubts he’ll last long—and until Toronto breaks down and lights up, Mercer is braced for a bumpy ride. Toronto can be a surly sonofabitch when things aren’t going his way.

Mercer steers back onto the cemetery’s main loop and lets the car drift back toward the archway that looms over the entrance. He’s about to joke that things look pretty dead here tonight when he spots a small, torn-up patch in the wet grass to his left, just off the road. Tire tracks—a pickup, maybe an SUV. Left sometime after the rain started, so they’re three hours old, at most. Mercer scans the area beyond the tracks. A darkened path weaves between the small, flat stones that pock the ground—foot traffic, he guesses, four or five people—and it runs about a hundred yards out to a decrepit part of the cemetery called Fern Grotto.

Hidden from view by an imposing stone tower and ramparts of ivy, broad-leaf ferns, and sprawling hydrangea, Fern Grotto is a circular, subterranean vault that held hundreds of bodies in its walls before a flood turned it into a pond full of yellowed, floating bones. These days it’s an empty, bramble-choked pit where Peninsula kids come to drink coconut rum from the bottle and screw. The grotto tower is an arresting sight: fifty feet high, with ivy snaking up its sides and converging at the top in a burst of green, an improbable tuft of vegetation that led Mercer, when he first saw it, to mistake the structure for an ancient, craggy-barked tree. A few weeks back, Mercer picked up two community-college kids (white male, 20; Asian female, 19) after he found them kneeling in the grass at the base of the tower. They were out of their heads on mushrooms and contemplating the enormous thing before them. “Lost souls,” the girl had intoned, stroking the naked, woody vines tenderly, with beatific concern. “The clawing fingers of lost souls.”

Mercer brakes to a stop. The vehicle is gone, and, he assumes, so are all of its occupants. Still, it’s his job to make sure.

“I have a theory about life,” Toronto announces, “and it’s this—”

Mercer holds up his hand. “Wait,” he says. He kills the engine. He listens.

“You need to hear this,” Toronto says.

“Later.”

“It’s the answer to your problems.”

Mercer points. “Torn-up grass. Foot traffic. Let’s take a look.” He gets out of the car, taking his flashlight with him. When Toronto doesn’t follow, Mercer crosses to the passenger side and knocks on his window.

Toronto rolls it down. He leans his head back in mock weariness, and Mercer notices for the first time just how protuberant Toronto’s Adam’s apple is. Seriously, it’s like the guy swallowed a golf ball.

“Boy Thirteen,” Toronto says dismissively, “they’re gone. No one’s here.”

“I want to check it out.”

“Go ahead. I’ll wait.”

Mercer hesitates. He’s acting like a typical rookie, he knows, chasing shadows while more seasoned cops roll their eyes. Toronto’s probably right. No one with any sense would stick around on foot in weather like this. All Mercer has to do is nod, get back behind the wheel, and drive them to the station, and they’ll be out of the cold and rain, and they can wait out the last two hours of the shift—the stay-awake hours, Toronto calls them—in the break room, where the TV will be tuned to hoops highlights or poker or some cable show about strippers.

“Changed your mind?” Toronto says. “Good, let’s go.”

Mercer rounds the front of the cruiser and is reaching for his door handle when the wind shifts and brings a sound to his ear. A sound. Barely audible, but it was there. He heard it. Something small, fearful, human.

“I heard something,” Mercer says through the open window. He flinches as the sky shoots a frigid dart of rain down his collar.

Toronto taps his cigarette.

“Listen,” Mercer says, and the sound comes again. “Hear that?”

“I hear not one damn thing,” Toronto says.

“Hold still. Close your eyes.”

Toronto stops tapping. “Of course, there’s Option Two, in which you stop wasting my time and tell me what it is.” He tucks the cigarette between his lips, where it hangs sadly, the paper splitting at the bends.

“Someone’s out there,” Mercer says. “At the pit.”

The sound comes again, louder this time, edged with fear and punctuated by a raw, scraping retch. “Well, fuck,” Toronto says. “I heard that.” He flicks the ruined cigarette out the window and joins Mercer in the rainy dark. “Fucking kids,” he says.

Mercer radios in, using the pick mike on his jacket collar. “Colma, Thirty-three Boy Thirteen.”

The dispatcher’s voice crackles in his earpiece. “Go ahead, Boy Thirteen.”

“On foot patrol, east side of Cypress Lawn. Suspicious circumstance.” He tucks his keys into his back pocket to keep them from jingling, and he and Toronto quietly cover the stretch of green between the cruiser and the grotto. Mercer holds his flashlight away from his body; when situations go sideways, gunmen will shoot at the light. (You have to learn good habits and practice them. Take nothing for granted. As Sergeant Mazzarella likes to say, Nothing will make you dead faster than an assumption. Everyone wishes the sergeant would lighten up a little, but they also know he’s right.)

A quick check around the perimeter of the grotto, the base of the tower. Nothing. The steel gate at the entrance to the vault is ajar. They hear the sound again—no, the voice, it’s a voice—a whimper, then a feeble moan. From inside. Mercer feels his pulse quicken, feels his hackles rise. Any cop will tell you: trust the hairs on the back of your neck; when they stand up, you pay attention. Mercer uses hand signals: he points at Toronto, then at his own eyes, then at his back. Watch my back. I’m taking lead. Toronto, whose neck hairs must be sending him a less-urgent message, shrugs and waves Mercer forward. Knock yourself out, Wonder Boy.

Mercer passes through the gate. A blackberry branch catches his sleeve, and the thorns scrape down the heavy nylon as he pulls away. He steps into the clearing and shines his flashlight down into the pit. Shards of glass catch the light, sparkling amid the brambles and cast-off leaves. A pair of jeans is splayed over a tangle of thorns—flung from above, probably—and a white high-top Chuck Taylor hangs in some cascading ivy, looking as if its owner stepped out of it in midair. Crumbling brick steps, hardly more than a red trail of scree, lead down into the pit. The only sound now is the pattering drizzle. The fog, sheltered from the wind, hangs dense and still.

Mercer follows the path that circles the pit. To his right, built into the earth, are the small, rectangular compartments in which the dead once lay. Dark tendrils of ivy cobweb the openings. To his left, along the pit’s rim, is a balustrade built from knotty, fist-thick birch limbs; in the bleaching glare of the flashlight, it looks to him like a fence of bones. Mercer steps quietly along the path, alert, coiled, ready to act.

He comes across a spot where leaves have been kicked away. Two empty tequila bottles lie in the dirt. Top-shelf stuff, Mercer notes. Stuff he can’t afford to drink. Also on the ground are a wood-carved pipe and a scattering of cigarette butts.

In the dark ahead of him, someone coughs. Mercer shines his light on the path and sees nothing. He summons his command presence, straightening into a powerful posture and urging his voice to boom. “Colma Police,” he says, feeling the authority resonating in his chest, his throat, his skull. “Identify yourself.”

Another cough, and a sudden rush of liquid. Chunky, strangled, urgent sounds.

Slowly (too slowly—as Mazzarella would say, the kind of slowly that’ll get you killed), he realizes the subject is lying inside one of the burial chambers. He shines his light along the wall into the far corner and sees bare legs protruding from one of the openings. The ankles are bound with duct tape that shines silver in the light. Toronto sweeps his beam across the area, scanning for other people, and Mercer hurries ahead, tugs away the curtain of vines that drape around the legs, and looks into the chamber. It’s a kid—white male, probably mid-teens—and he’s been shoved in headfirst, on his stomach. Naked from the waist down, and just a damp white T-shirt on top. Wrists duct-taped behind his back.

“I’m making contact,” Mercer calls to Toronto. “Are we secure?”

“All clear,” Toronto says.

Mercer touches the boy’s calf. His skin, wet from the rain, is pale and blue-tinged. Mercer finds a pulse from the femoral artery, and it’s slow, draggy, erratic. An earwig skitters across the kid’s thigh, and Mercer sweeps it away.

Toronto comes up behind him. “Hypothermic?”

“Think so.”

“So what should you do?” Toronto’s voice is level, cool.

“Try to rouse,” Mercer says, impatient. It’s an emergency, not a goddamn training session.

“How are you going to do it? Sternum rub?”

“Of course not. Can’t get to it. Can’t move him.”

“So how, then?”

“Rub somewhere else,” Mercer says.

“Where? You going to rub his ass, for instance?”

“I’m not rubbing his ass.”

“Whether you do or not, I’m telling everyone you did. You’ll be known forever as Mike Mercer, Ass-Rubber. We’ll get you vanity plates that say i RUB ASS.”

“We’ve got a situation here. Let me think.”

“Don’t think. Just deal with it. Unless you need me to do it for you.”

Mercer makes a fist and rubs his knuckles up and down the sole of one of the kid’s cold bare feet. “Hey, buddy,” he says, raising his voice. “Can you hear me?” No response. Mercer tries the back of his knee and elicits a dwindling, wordless groan. The air stinks of the kid’s vomit, and Mercer has to pull away for a moment to gird himself.

“Let’s get him warm,” Toronto says. “I’ll grab the blanket.”

Mercer radios in. “I have a ten-forty-two, code three.” Medical emergency, request for ambulance, with siren, all due haste. “Subject is a wh

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...