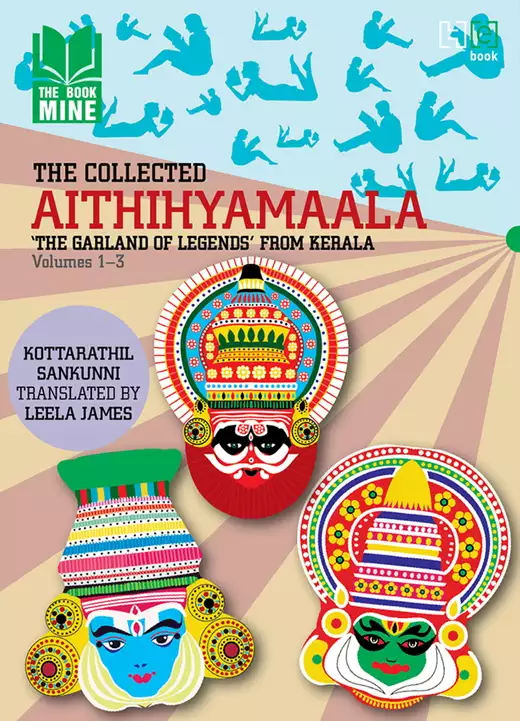

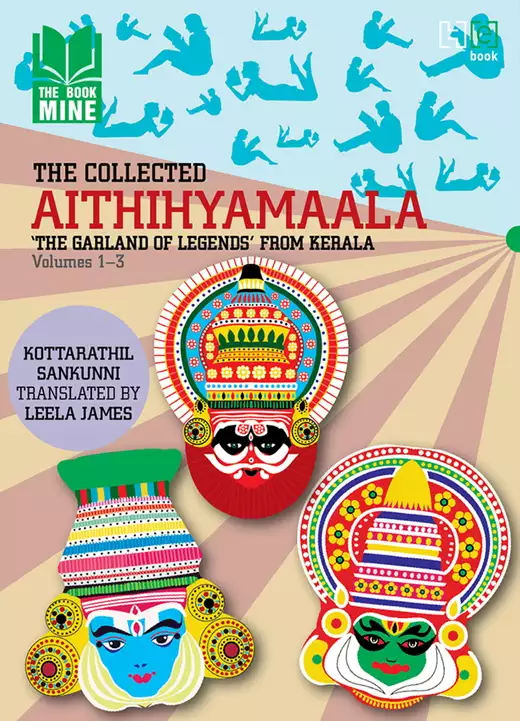

Aithihyamaala

- eBook

- Paperback

- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

This special e-edition combines all three print volumes of the collected enduring legends of Kerala in the Aithihyamaala, the garland of legends. Yakshis, gandharvas, gods and demi-gods. Famous poets and learned Ayurvedic doctors. Magicians, conceited kings and Kalari gurus. Faithful, intelligent elephants and their fatherly mahouts. A vibrant and diverse cast of characters brings to life the ancient stories. The original collection of 126 tales, were documented over 25 years and written in the 1900s by Kottaaraththil Sankunni. These stories of well-known figures in Kerala folklore were first published in Bhashaposhini, the renowned Malayalam literary magazine. This edition of 50 stories, meticulously curated and translated by Leela James, transports you to the magical world of history, myth and fantasy of more than 100 years ago. Wisdom and vice, revenge and loyalty, imagination and fact, faith and superstition are intricately intertwined to create a collector?s edition for lovers of legends, Malayalam folklore and Indian literature.

Release date: June 20, 2015

Publisher: Hachette India

Print pages: 586

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Aithihyamaala

Kottarathil Sankunni

I have ventured to translate a few of these legendary stories, at the earnest insistence of my son, Viju, and daughter, Soumya. While staying with Soumya in Ithaca in 2007, she told me that one of her class of research students asked her if she knew anything about the Kerala yakshis and gandharvas which she came across in her research. Fortunately, Soumya had remembered the story of Kadamattaththu Kaththanaar which I had recounted to her a long time ago. So she got the brilliant idea to get the Kerala folktales of Aithihyamaala translated for the benefit of those who cannot read Malayalam and thus she asked me if I could undertake this work. Since my children also cannot read fluent Malayalam, which is a pity, of course, I thought I would try, as best as I could, to translate a few of these legends for them to read and enjoy. Thinking of my incredible venture which I started five years ago, when I was past 75 years old, I am unaccountably surprised at myself and so I ask you to forgive the faults you would definitely find in my narrative. I have tried my best to keep up the Malayalam style of narration followed by the author.

It is universally accepted that every country has its own popular folk tales and legends, come down to the generations by word of mouth, from the age of storytelling. Kerala had its own such stories of its temples, kings and kingdoms, their own traditional religious beliefs and social customs. Most of these need not be true, some may have traces of truth but the main importance of these, is that we are shown the life ‘of those times’, the long-disappeared or slowly disappearing religious rites, customs and manners and the political structure of those days. People lived then just as we also ‘live’ now, but differently.

Aithihyamaala is a collection of Kerala legends, painstakingly collected and excellently written and compiled by a man named Kottaaraththil Sankunni. He was born on 23 March 1855 at Kottayam in Kerala. It is unbelievably true that he never attended any school. Till the age of 10, he was tutored by private teachers [called aasaan in Malayalam]. After 17, he studied various subjects of interest, including indigenous medicine, under well-known masters. From the age of 26 onwards he had to take up responsibilities of the family, but he continued his education on his own! Thus it was from among his incredibly varied interests that we are fortunate to get the book, Aithihyamaala, first published in 1909.

Written in Malayalam, it is a vivid, lucid narrative of captivating interest, which not only holds our attention but encourages us to think; a modern style of educating us through fun and fantasy.

The first story I chose to translate (Aazhvaancheri Thambraakkalum Mangalathth Sankaranum) is said to be related to my own mother’s family – a maternal heritage! An ancestor from my mother’s family (her father’s side) is supposed to have come from this family of Aazhvaancheri Namboothiris long ago, and later converted to Christianity. This was related to me by my mother’s second sister whose name was Thankamma and whom I called Thankochamma. God bless her memory.

Leela James

New Delhi, August 2014

1

The Landlords of Aazhvaancheri and Sankaran of the House of Mangalam

(Aazhvaancheri Thambraakkalum Mangalathth Sankaranum)

Near the famous illam of the Aazhvaancheri landlords, lived a Nair named Sankaran. His family name was Mangalaththu. He was the cowherd of the Aazhvaancheri illam and his job was to take care of the herd of around 150 cattle – take them out every morning to graze in the fields and bring them back to their cowshed by sunset. Sankaran found it extremely difficult to manage them all by himself and he was at his wits’ end. One day when the cattle were running all over the fields and not listening to his frantic calls to come back, Sankaran felt desperate and, lifting his stout stick, he gave a heavy blow to one of the cows. Immediately the cow fell down and died. Though foolish and ignorant, he was careful to take stock of the spot where he had hit the cow and, from then onwards, whenever the cattle were disobedient to his call, he would hit them at the exact spot and kill them. Very soon their number diminished and so did Sankaran’s woes. He felt quite relieved.

Then one day, the landlord came to inspect the cattle. He saw that the cowshed was almost empty except for a few cows that looked miserably thin. He called Sankaran and asked, ‘Where are our cattle?’

Sankaran replied, ‘Ah! Yes, Sir. This is what will happen to anybody who would try to trouble me. They were all scoundrels; they never listened to me; such a difficult time they gave me; and so, they deserved what they got!’

Completely bewildered, the landlord once again asked Sankaran to tell him where they were. Sankaran then told the landlord, ‘They all died!’ and went on to narrate how it happened.

Though badly shaken by what he heard, the landlord understood that Sankaran did not realize the magnitude of his crime. So he patiently explained: ‘Whatever has happened is over. But apart from the monetary loss, Sankaran, do you know that you have committed the enormous sin of cow-slaughter?’ Then he explained the meaning of sin and heaven and hell and the rewards and punishments of our deeds. Poor Sankaran was aghast. Full of remorse he asked ‘Now what shall I do?’ The Master answered, ‘Only a dip in the holy waters of Ganga can cleanse you.’ Once again, ignorant of such a possibility for forgiveness, he asked ‘Are you sure?’ When he was convinced of the result of making such a pilgrimage, Sankaran readily agreed to go to Ganga without any more delay. Accordingly, he made his obeisance to his master and left for Kasi.

On Mount Kailash, Sri Parvathy was asking her husband Paramasivan, ‘My Lord, is it true that all those who bathe in the Ganga are cleansed of their sins and they all attain moksha?’

Shiva answered, ‘Oh no, definitely not. Without faith and true devotion, no one attains moksha. Such people are very rare to find nowadays; bathing in the Ganga, without faith, is of no use, whatsoever. Tomorrow I shall prove this to you.’

The day after this conversation on Kailash, the divine abode of Lord Shiva and his consort Parvathy, our Sankaran Nair reached Kasi. There were many devotees at the ghat, either bathing or getting ready to bathe. Sankaran too mingled with the crowd, all set for the holy dip. Just then, Shiva and Parvathy, disguised as an old Brahmin couple arrived at the banks of the river. Trembling with uncertain steps the old Brahmin began to climb down towards the waters, when suddenly he slipped and fell into the river and started struggling. It was certain that the helpless old man was going to drown and his old wife cried out in agony for help and all those nearby came running. Then the aged Brahmin woman quipped, ‘Oh please wait for a minute and hear me; only those without sins should touch him or he’ll die.’ Hearing this everybody stopped and started to turn away, saying, ‘Of course we had our holy dip, but how do we know if our sins are truly washed away? Can we take the risk?’ Meanwhile the old Brahmin was sinking. Suddenly Sankaran Nair came forward. He thought, ‘Why should I doubt? My master had told me that Ganga washes away our sins and I had my dip in the holy river. So now surely I am without any sin.’ Believing so, he stretched out his hand and pulled the old man safely out of the water.

Back in their holy abode Shiva told his consort, ‘Among all those you saw bathing at the ghat only one person had the faith and only he will come to heaven.’ Parvathy understood and agreed with Shiva.

Sankaran Nair spent the rest of his days in Kasi and died there years later.

After Sankaran had left for his pilgrimage, misfortune hounded the illam. There were losses in money and men and cattle, children died in their childhood, and the powerful landlords felt there must be some reason for this bad luck. So they consulted astrologers, as was the custom at the time, and learnt that the landlords too were being punished for the crime committed by Sankaran, who had sinned without knowing it was a sin; but their crime was greater as they neglected to supervise the welfare of their cattle. As penance they were advised to grow fodder for the cattle in a large area of their property and leave it for the cattle to freely graze and feed. They did this as a penance and as a result flourished in later years. Wealth, power and glory returned to the great household.

But the saying goes that, as a precaution, they did not rear cattle anymore.

[Translator’s Note: At the end of this story in the original, there is a four-line verse which explains that in the course of time, the dynasty of Aazhavaancheri came to eliminate as part of their penance, ten materials starting with the Malayalam letter, ‘pa’, such as pasu = cow; paaya = mat; paththaayam = granary; palaka = flat timber piece used for sitting or construction, padattivaazha = a kind of plantain tree; paithal= child; panam= money; panambu = bamboo mat; padippura = gate house, etc.]

2

Bhattathiri of Kaakkassery Illam

(Kaakkasserry Bhattathiri)

During the rule of Maanavikraman Sakhthan Thampuraan of Kozhikode, there was a custom of having a gathering of all the well-known Brahmin scholars of the period at his court. They conducted a competition of erudite discourses, scholarly debates and discussions and whoever won was awarded a bag of money as well as other royal gifts; the custom was to divide the Vedic Puranas into 108 parts and conduct the contests in each part and present 108 awards to the winners, and the senior-most Brahmin scholar was given a bag of money as a special prize. It was a prestigious honour to participate in these contests and scholars used to come from far and wide.

After a few years, the number of worthy Malayalee Brahmins [of Kerala] dwindled to such an extent that there was almost no one to compete, which made it easy for the Brahmin scholars from outside Kerala to win all the prizes. During this time, there came from outside Kerala a famous scholar named Uddhanna Shaastrikal to compete in this famous debate. He was well-known as a great scholar well-versed in the Vedas, Puranas and their interpretations, but was disliked for his notorious arrogance. It was said that he entered Kerala by singing a verse that read, ‘Oh you ignorant elephants, flee, flee; the great lion among scholars is coming through the jungle of Vedic Knowledge.’

He defeated all those who challenged him and won all the 108 bags of prize money. As a result of this feat, the king was overcome with respect and honour for this foreign Brahmin. He therefore invited him to stay at his palace permanently. Needless to say, every year he won all the awards and enjoyed the luxurious life of the palace too.

When things were in such a sad state, the Kerala Brahmin scholars felt ashamed and distressed and they were determined to overcome this shameful agony. Therefore, a few important men among them met in the Guruvayur Temple to plan how they could defeat the arrogant Uddhanna Shaasthrikal and also get rid of him.

They came to know then that at the Kaakkasserry illam, a young wife was expecting a child. Delighted at the news, the Brahmin scholars sent her a small ball of butter into which they had magically concealed some mantras and she was told to consume daily a dose of this butter and pray to the Lord Guruvayur Appan every day.

Sure enough, with a daily dose of the powerful mantras, she gave birth at the right time to a healthy and handsome boy, who later came to be known as the illustrious scholar, Kaakkasserry Bhattathiri.

Even from childhood, he was exceptionally intelligent. His father died when he was just three years old and according to the Hindu rites, there follows a year of abstinence.

As part of the rituals, a lunch meal was kept outside daily, [as if in remembrance of the dead dear one] and someone would clap for the crows to come and feed on it. The belief was that the crows would be pleased to partake if the rites were observed correctly. Otherwise they would not touch it. This annual funeral rite was known as beli eduka. When this was being done in his illam, the little boy would recognize each crow and point out correctly to his mother those crows that came new on that day as well as differentiate those which came earlier. Inexplicably, he was found to be right. Due to this extraordinary gift, he became famous as Kaakkasserry Bhattathiri. It is almost impossible for ordinary people to recognize each and every crow one sees daily and hence, it was all the more remarkable that this boy could. It showed the unusually keen observational powers and sharp intellect of the boy.

It was customary among the Brahmins to have their thread ceremony at the age of eight and their initiation into the Vedic instruction and mantras afterwards. But the boy was exceptionally gifted and so Bhattathiri started his education at the age of three, and his sacred thread ceremony was held when he was five.

An amusing incident that happened in early childhood showed his quick wit and bright mind. When he was five years old, he used to go with a servant to the nearby temple of Mookkuthala Bhagavathy, which was also called Mookkattaththu Bhagavathy. Once while returning from the temple, someone on the wayside asked him, ‘Where have you been?’ The little boy answered, ‘I had gone to worship the goddess.’ ‘And what did she say?’ asked the man. To this, he replied in a couplet which had the following meaning; ‘I saw the goddess who sits on the tip of one’s nose.’ [Now mookku means ‘nose’ and attaththu means ‘at the tip’ and hence he had literally translated Mookkattaththu Bhagavathy as the goddess who sits on the tip of one’s nose. But the tip of the nose is also the common spot where the yogis touch while meditating]. The meaning, in short, was that he went to see the goddess who sits at the tip of one’s nose and the yogis who were present at the temple.

Hearing this reply, the older man remarked, ‘What an unusual child!’ and went on his way. This definitely showed his lightning comprehension and intelligent wit even as a child.

Before he reached adulthood, Kaakkasserry Bhattathiri was a full-fledged scholar, a powerful debater and became famous as a secular speaker and interpreter of the Vedas and Puranas. Therefore, the other Kerala Brahmin scholars pressed him to attend the Annual Meeting of Scholars in the Royal Court of Maanavikraman Sakhthan Thampuraan that year and that meant that he would get a chance to compete with the famous Uddhanna Shaasthrikal. He agreed to do so and arrived at the Thali temple where it was held. The Saasthrikal used to take a parrot with him to represent him in the contest. When he heard this, Bhattathiri told his servant to carry a cat along for the Assembly. When he entered the durbar, the king and the Saasthrikal were already present. When the king saw the youngster, he asked him, ‘Unni, why have you come here? Are you entering in today’s contest?’ He answered, ‘Yes.’ Then Saasthrikal felt an urge to poke fun at the lad and remarked, in Sanskrit, ‘The body is short’, to which the boy retorted immediately, also in Sanskrit ‘No, no, the body is long, but the interior is short!’ in order to ridicule the appearance of his opponent. In doing so, the latter turned the use of just the sound of the first letter of the alphabet to his advantage and to the other’s discomfort. The response from the Bhattathiri was so quick that his opponent could not find an answer and felt completely discredited.

The contest started. The Saasthrikal seated his parrot in front of him, observing which, Bhattathiri brought his cat forward. The parrot was struck dumb seeing the cat. As the debate progressed, everybody saw that Bhattathiri could powerfully demolish all the arguments put forward by the opposition and was at an advantage to win. Realizing the imminent defeat and discomfiture of his protégée, the king suddenly announced – ‘Let us put an end to this debate with just one more question; whoever gives a more meaningful interpretation for the first verse in the book of Raghuvamsa will be declared the winner today.’ He gave this order because he was absolutely sure that none in the Assembly could do this better than the Saasthrikal; moreover, he did not wish to see the supreme reigning scholar being defeated by a newcomer and, that too, a mere lad. In order to stop this, the king deliberately came to his rescue.

Both the contestants agreed. The senior was given the first chance and he quoted the verse and gave four different meanings and paused, feeling that no one could better his arguments. Even the king believed so and felt comfortable and sure that the Saasthrikal would win. Then it was the turn of Bhattathiri. He brought out eight clear and relevant interpretations of the same verse. Now the king and the courtiers could not but acknowledge that Bhattathiri was the unquestionable winner and awarded him all the 108 bags of money.

Then the Saasthrikal demanded, ‘At least the bag for the senior should come to me since I am the oldest in this assembly today’ and for that Bhattathiri argued, ‘Oh no, it is not so. My servant here is eighty-five and the oldest and all of you have admitted that regarding Vedic scholarship, I am the oldest today.’ Therefore, that bag of money should come to us.’ Since no one could defeat him in quick-witted reasoning and intelligent argument, Bhattathiri collected all the 109 bags of money on that day. Doubtless, it was a red letter day of magnificent triumph for the Kerala Brahmin folk but an unforgettable day of shame and defeat for Uddhanna Saasthrikal and party.

Both these Brahmin scholars met at different conferences and contested strongly even in later years, but the Saasthrikal could never defeat Bhattathiri at any time.

After their first meeting in Thali, it was the turn of Bhattathiri to carry away all the prizes every year as there was no opponent in Kerala or elsewhere worthy enough to defeat him.

As he grew older in years, his keen intellect and incomparable quick-wittedness also improved further but he became a self-imposed ascetic and did not care to stay long at home. A strong believer in the adage ‘All is Vanity’, Bhattathiri travelled extensively from place to place, visiting renowned pilgrimages and places of interest.

During one of his trips, he was once staying in a public rest house, where there were several more such travellers and wayfarers, spending their time. Suddenly there was some trouble amongst them and they quarrelled and started abusing each other violently. Someone ran to bring some government officials to stop this fight. When both the quarrelling parties began to blame each other, the officials asked if there were any witnesses and one of those involved said, ‘Yes, there was a Malayalee Brahmin watching us.’ So they sent for Bhattathiri who came and described every detail of the fight. Again the officials asked him, ‘Can you mention what were the vocal abuses they threw at each other?’ Our worthy Brahmin replied, ‘Actually I do not know their languages but I shall try to remember what they said’ and the prodigious intellect repeated word for word all the abuses that had been spoken in the different languages of the travellers – who had come from Karnataka, Maharashtra, Andhra, Tamil Nadu and various places in North India and even some who spoke in Hindustani!

This extraordinary person did not bother about untouchability or casteism and mingled freely with everybody. He would eat the food offered to him by anyone, enter all temples and places of worship and completely ignored the objection raised by the rest of the Brahmin community. His broad-minded view was that ‘a good bath is to clean the exterior of the body; it does not clean one’s insides.’ The high-caste Brahmins definitely could not accept this indifferent nature of the scholar and they unanimously agreed to refuse him entry into their own homes or the temples and abused him behind his back but would always hold their intolerant tongues when he was present. They knew for sure that they could find no reasonable proof or any just argument to excommunicate him in this respect and also that any such reason would be radically demolished by the great scholar. Therefore, writhing within with anger and jealousy they conspired to punish him because they had begun to consider him a threat and danger to their community.

At another Assembly of scholars, where the ruler Sakhthan Thampuraan and all the Brahmins were present, Bhattathiri had again collected all the awards when there was a short dialogue between him and the other Brahmins. It was a question and answer style in Sanskrit which went as follows:

BRAHMINS: ‘What should be done in the time of danger?’

BHATTATHIRI REPLIED: ‘Remember the feet of the goddess.’

BRAHMINS: ‘How does such remembrance help?’

BHATTATHIRI: ‘That can bring you even Lord Brahma’s service!’

After this interesting conversation, each went his own way.

Very soon, the Brahmin clan started a strict worship of the Bhagavathy with the complete paraphernalia of a devotional pooja with mantras etc. After forty days of such strict observance by the Brahmins, on the forty first day, unexpectedly Bhattathiri arrived at the temple. Standing in the outer courtyard, he asked someone there for a glass of water to drink. After he drank the water, he put the glass upside down and said, ‘I am an outcaste; therefore, I am not coming inside or touching any of you.’ Saying so, he left the place and was not seen again. He continued on his travels. No one knows, till now, how or when he died.

Since he did not care to have a family life, and as there were no more men folk in that family, his family line ended with his death.

3

Nambi of Aalaththur

(Aalaththur Nambi)

Aalaththur Nambi’s illam was situated in Aalaththur of Ponnani district in Malabar in north Kerala. He acquired another house in Choondal in the old Cochin State where there was once upon a time, a physician named Choondal Mooss. It so happened that once this family had no male members but only a young Brahmin girl. A certain Aalaththur Nambi married her and was subsequently adopted by the Choondal Mooss family, as its heir and protector.

At a later period, this Aalaththur family lacked male members and a certain Namboothiri from the Karuththapaara illam married the only girl left in the family. Thus the Aalaththur Nambis and Karuththapaara Namboothiris were connected by marriage and later participated in all their family festivals and ceremonies.

The Aalaththur Nambis were famous physicians with an almost ‘divine’ touch in their healing and medication. There are interesting legends illustrating how they acquired these exceptional talents.

Near the Aalaththur Nambi’s illam, there was a well-known Shiva temple called Vaidyan Thrukkoil. Long ago, a Nambi from this illam used to visit the temple twice a day to worship and on one particular visit, he was surprised to hear two birds on a banyan tree, making a peculiar sound, ‘korukku, korukku’. A few days later, Nambi stopped under the tree and whilst looking up, gave them an answer in a Sanskrit couplet and went home. From the next day onwards, he never heard or saw those birds again.

The conversation was like this: The birds asked the question, ‘korukku’ meaning ‘kah’ + ‘arukku’ = ‘korukku’ which can be translated as ‘who is without illness’ or ‘who is healthy’?

Nambi’s answer in couplet was: ‘One who eats moderately, walks a little after meals, sleeps on his left side, excretes regularly and does not show excessive desire for women, such a person is without illness – and thus, will be healthy.’

Whether they accepted this answer or not is not known, but all the same the birds disappeared.

Two days later, a couple of Brahmin boys came to Nambi and requested if they could stay on the premises and learn medical science from him. Nambi agreed and the boys were accommodated in the illam. But the youngsters turned out to be extremely mischievous and were up to all sorts of infuriating pranks.

Surprisingly, Nambi tolerated it and never lost his temper with them; moreover, he found them to be so exceptionally brilliant and intelligent that he patiently put up with all their nonsense. They would deliberately disturb his class by either not paying attention or ask too many questions which they would answer themselves with as many interpretations to the problematic situation, so that eventually Nambi realized that he was learning more from them than they did from him. No wonder that Nambi could never chide or rebuke them although there was no end to their inexplicably irritating behaviour.

One day, when Nambi was away, these two boys set fire to the padippura and burnt it down to ashes. Nambi saw it when he returned but kept quiet without scolding or asking for an explanation.

Another day it was the death anniversary of Nambi’s father. Before performing the necessary rituals, Nambi went to take his bath. Just then, there came two men of a lower caste to the gate begging for food. Seeing them, these boys entered the kitchen, took the meals kept ready for the beli and promptly gave it to the two beggars. When Nambi came from his bath, he learnt what happened but without a word of rebuke to them, got the entire meal cooked again and performed the rites.

On another occasion, Nambi took these two youngsters with him to visit one of his patients. On the way, whilst crossing a bridge, they pushed Nambi down into the river and he had to swim over to the other side and proceed on his way in damp clothes. Again Nambi suffered it patiently.

Nambi had a patient who constantly suffered from severe headache. Whenever it became unbearable, the poor chap would come running to Nambi who gave him medicines which could only give temporary relief but did not cure him. One day Nambi was not at home when the man came screaming with excruciating pain. Hearing his agonizing cries, the two Brahmin boys came out of the house. They looked at him and without a word they went into the backyard, where they found two types of leaves, and then calling the man, into a room, they locked the door. Full of curiosity, Nambi’s young sons went to the locked door and peeped in through a hole in the wooden partition and saw what was going on inside.

The two Brahmin boys took one set of the leaves, crushed it with their hands and squeezed out the juice which they poured on the head of the patient. Then the whole skin with the hair came loose which they kept aside and, after cleaning the scalp of the numerous insect-like creatures sticking to it, they replaced it and poured the juice from the second set of leaves by which the skin with the hair stuck well to the head, and remained intact as before. As soon as this was done, the patient felt completely relieved of pain and left without even waiting for Nambi’s return.

But as they came out of the room, the Brahmin boys caught Nambi’s sons spying and they admonished the boys saying, ‘If you peep like this you will surely get a squint.’ Then they wiped their hands on the pillar nearby and threw away the sediment leaves.

When Nambi returned he had his bath and sat down to eat with his sons who immediately started telling their father all what they had seen.

Just then, the two Brahmin boys came to him and said: ‘The time has come for us to depart. We lived here with you and learnt many things but also harassed you in different ways. Yet you were always kind and generous and tolerated our misdeeds. We have nothing to give you in return, but this book. Please accept this. Whenever you feel incompetent or unsure, look into this book and you may find a remedy or a relief in these pages. But this should not be seen by anyone other than the members of your family.’

As Nambi was eating with his right hand, he stretched out his left hand and took the book from them. He got up from his seat, and clenching his soiled right hand and holding the book with his left, he accompanied the two Brahmins to the door where there was a short dialogue between them:

NAMBI; ‘Please tell me now, who are you?’

BRAHMIN PAIR: ‘Why do you want to know?’

NAMBI: ‘Well, it doesn’t matter, but I know for sure that you are not ordinary human beings. So I asked out of curiosity.’

BRAHMIN PAIR: ‘In that case, take us to be either birds or divine beings, whichever.’

NAMBI: ‘Why did you come here?’

BRAHMIN PAIR: ‘In order to enhance the fame and worth of Ayurvedic system of medical practice.’

NAMBI: ‘Why did you set fire to my outhouse?’

BRAHMIN PAIR: ‘Because at that time there was an unfortunate chance of fire to your entire illam, so we diverted it to the smaller building; still, be sure that the fire is still destined to take place one day in the future.’

NAMBI: ‘Why did you give away the meal for the beli to the two low-caste beggars?’

BRAHMIN PAIR: ‘Because they were actually your ancestors; as the time for the ritual was fast diminishing, they came disguised; if they were not fed when they arrived, they would have cursed you in anger; consequently your family and wealth would have been destroyed. Hence we diverted the danger by doing what we did.’

NAMBI: ‘Why did you push me into the river?’

BRAHMIN PAIR: ‘Because just at that time, the holy confluence of the Ganga, Yamuna and Saraswathy was taking place in this river

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...