- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

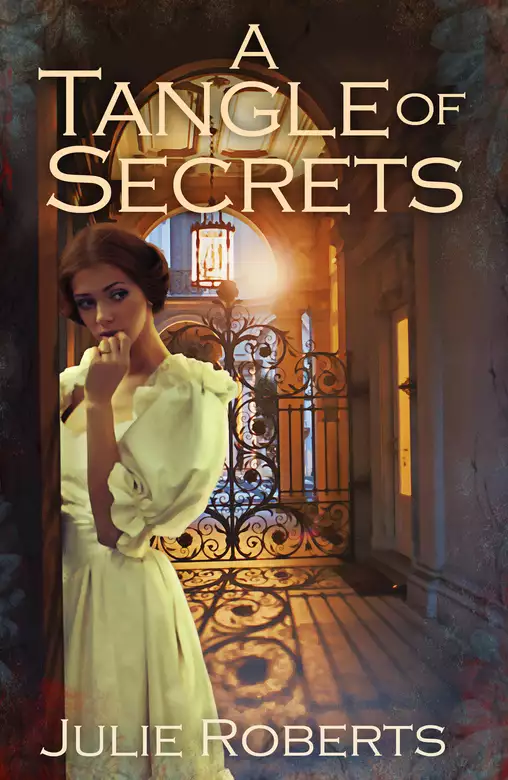

Synopsis

Hannah Dudley is left impoverished in New York by her brother. One evening she finds a stranger, Christopher Forsythe, ill and dying on her doorstep. Leaving him there will ensure his death. Taking him in will ruin her reputation. A marriage certificate will protect her. Not even Hannah's devoted nursing can save Christopher. Months later, she receives an unforeseen letter from Christopher's brother, Lord Marcus. He offers, at the request of his mother, a place in their home in London. Hannah is shocked to find she is now part of an aristocratic family. Reaching England, she finds the ton's social restrictions are difficult to deal with. A forbidden love grows between Hannah and Marcus, even though they know the church will not sanction their marriage. Hannah is faced with only one choice. She must take a journey that will break her heart. Leave Marcus and return to America...

Release date: September 11, 2019

Publisher: Accent Press

Print pages: 300

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

A Tangle of Secrets

Julie Roberts

Hannah pulled her shawl tighter. This was the time of day she feared, dusk fading into night, when she walked past homes with their doors locked, shops shuttered against thieves. She hurried on past narrow alleyways where she always cast a wary eye. Often the sound of breathing and shuffling boots warned her someone may be waiting and watching.

Since the great storm had roared through New York a month ago the city had been in turmoil. The giant surge of waves had been taller than a house; the sea a relentless monster that crashed into the piers, wharves and warehouses. The wind driving the storm like the hand of the devil bent on destroying everything in its way. She had feared for her life. She feared the same now, but not from the elements, but from the people who had been made homeless, were hungry and had a need of work to earn a wage. The priority was the waterfront. When the ships could offload their cargos, men would have jobs and New York would come alive again.

Hannah shivered, not from the cold because the autumn weather was pleasant. There had been no rain for several days and the dirt road was difficult to walk along as she avoided the hardened rutted cart tracks. She side-stepped a heap of horse dung, still steaming fresh and she cupped her hand over her nose and mouth. Like a pale ball she saw a turnip lying next to it and picked it up. She could add it to her store box of two carrots and three potatoes. Every cent saved kept her one step farther away from destitution. She closed her eyes for a second; shutting out the constant reminder of the squalor she walked through every day. But this evening she had sold all of her cakes and there were enough dollars in her pocket to pay the rent.

She turned into Merchants Lane. A breeze blew her cotton dress between her legs. She lifted her shawl to cover her auburn curls to stop them flying across her face. The smell of the docks, some familiar and some now very unfamiliar, mixed together. It carried strongly towards her as she hurried to get home. On either side, the damaged buildings had miraculously supported each other from falling apart. They were a hotchpotch of a carpenter’s yard, a blacksmith’s forge, general stores and the homes of immigrants. The more prosperous settler occupied the whole of the property. Poorer families could only afford to rent one room. The unmarried men with more money rented two rooms.

The sight of her door chased away her fears. Here was her haven, her home and safety from the rogues and thieves who roamed the waterfront, spending their ill-gotten money in the taverns and gaming houses.

In two seconds her relief turned to panic. A man lay huddled and groaning against her door. Her first thought was to turn and run. If this was a ruse, he would be after what she had in her pocket, or her body. Many a girl disappeared without trace into the brothels.

Hannah looked up and down the road. There was no one to be seen for any help. Merchants Lane was not a main highway. She had dallied after selling her cakes, gossiping with Mrs Tregarron and now she was left alone with a tramp at her door. Her second sensible thought was to get Harmina. She ran to her neighbour and banged on the bakehouse door. She waited, slipping her shawl off her head and tying it round her shoulders. Where was Harmina when she needed her? She clenched her fist and pounded harder. Then she remembered it was Monday evening and the family visited Harmina’s cousin every week.

She heard the man still groaning and muttering unintelligible words. She went back to him and shook his shoulder. ‘Get up and away. I’ll not have a vagabond sleeping off his sins at my door.’ She gripped his coat and pulled; he was nothing more than skin and bone. His eyes were closed, and in the half-light he looked shrivelled and old. She touched his forehead. He was not drunk but burning with fever. What should she do? Common sense told her to leave him, let him crawl away when ... but he was too ill. Hannah was sure he was too weak to hurt her, and she couldn’t leave him on the road for the dogs and rats to feed on. She waited for her heart to stop pounding. She had to make a decision. Compassion pushed away her fear and she pulled the key from her pocket and unlocked her door.

The coldness of the room sent her directly to the fire. She poked the grey ash and nestled a few sticks, blowing gently until a flame caught and then laid a log alongside. The burst of flame gave her enough light to pull the day-curtain aside that concealed her bed. She stripped back the covers and returned to where the man lay. He was coughing uncontrollably. When he stopped she gripped his coat and dragged him into the room, kicking the door closed. Hannah paused, breathing deep and gasping; he was heavier than she had thought him to be. She lifted his shoulders, placed her arms around his chest and heaved, sliding him little by little until he lay full length on her bed, then she wrapped him fully clothed to his chin.

Hannah wasn’t cold now, but her shoulders and back hurt from the strain of pulling and she sat on the floor. She was a fool. As the minutes passed the effort to get up became harder. Why had she given herself an added responsibility she could well do without? But, he was in her bed now and scolding herself did little good. She got up and took the remains of a candle from the mantelshelf and held the wick to the fire’s flame. The light threw most of the room into focus: a man of uncertain means, a cold brick floor, a table and two stools. The only comfort was her rocking chair with its embroidered cushion.

The man’s breathing seemed to be a torture to him. Hannah knelt beside her bed and brushed his damp hair from his burning forehead. He needed medicines, but did he have any money? Her rent was due tomorrow. If she used even part of it the landlord might not give her credit until next week. He had evicted others with a flick of his hand, knowing he could find a new family before those leaving had packed their bags.

She took the drawstring purse from her pocket, weighed it in her palm, medicine or rent? The stranger started coughing again. Hannah didn’t wait to ponder her choices, she got up and raced out and banged on the door of her neighbour.

‘Harmina, are you there? I need your help.’

The door opened. ‘Ya, what is the matter, so much noise, Hannah Rose? Can I not arrive home and take off my shawl before I am wanted?’

‘I have a man in my bed, he is very sick. Please, could your Jared go for Heer Horstman? I have the money tell him, but he must come quickly.’

‘And where did you find this man to put in your bed?’ The Dutch mother folded her arms and waited for Hannah’s reply.

Heat burnt her cheeks. ‘Harmina, you know I’m not that sort of woman. He was huddled outside my door.’

‘You are a foolish, soft hearted girl.’ Harmina called to her son, ‘Jared, run for Heer Horstman as though the dyke has broken. Take him to Hannah’s room.’

‘Thank you. I must get back to him.’

An hour later, the wizened apothecary sat at the table and shook his head. ‘There is little I can do. He has the consumption and his lungs are too far gone for my help. If you can keep him warm and fed, he will last a little longer. If you turn him out ...’ He shrugged his shoulders, ‘that must be your decision, my dear.’

Hannah placed her rent money on the table. ‘Thank you. I will do what I can. He should not die alone.’ Heer Horstman stood up and patted her shoulder. He left, leaving her money untouched on the table.

His kindness brought tears to her eyes. She didn’t have to face the rent collector with an empty purse. The last time she had begged a day’s grace he had leered close to her face and licked his lips, saying, ‘I could bypass you this week for five minutes of your time.’ She shivered. He was a vulture, feeding off the poor.

She set a stool beside her bed and sat down. The man was asleep and she studied his face. The pallid skin stretched over his bones, the black smudges under his eyes were signs he had not slept well for some time. And he was younger than she had first thought. She rubbed her eyes and yawned; she had been up before dawn to work in Jozef Mulder’s bakehouse. Each day Jozef found her free cakes that he called ‘bad bake’ for her to sell and keep the money. Without their help she would not be living here, but in a hell-hole for the penniless tramps, or worse. Cradled in her candlelight world, warmed by the fire, with the flames making patterns on the wall, she closed her eyes.

A moment later she felt a finger touch her cheek. She lifted her head and looked into the grey eyes of the stranger. ‘You’re awake?’ She looked away, conscious of how close she was to him.

‘Yes. Where am I?’

‘I found you at my door. You are very ill. Heer Horstman said ...’ Hannah stopped. She didn’t know how to tell him he was dying.

‘It’s all right. I know what he said. I have known for months it would come to this in the end. I didn’t expect to see an angel with beautiful green eyes sitting by my side. What is your name?’

‘Hannah Rose. What’s yours?’

‘Christopher.’

‘Are you a settler?’

He shook his head, a smile making his lips lift at the corners. ‘I am definitely not a settler, Hannah Rose. I could be called an adventurer, or a gambler, but never a settler.’

‘Do you have any money?’ She hesitated. ‘Heer Horstman will need paying and so will other things ...’ Hannah couldn’t bring herself to say there would be a burial to pay for. She straightened her back; sentimentality was not an emotion she could afford. Already she had gambled with her rent. Only the apothecary’s compassion had saved her. ‘You have improved much since I found you. I do not wish to be harsh but it is best to sort out your wishes now.’

The only reaction from him was a sigh. ‘I feel much revived because of your help. I have silver dollars, I can settle my dues.’

Hannah said nothing for a few seconds. ‘Why are you telling me this? I could rob you of your money and –’

Christopher raised his hand. ‘An angel sent from heaven wouldn’t do such a thing. I must trust you, Hannah, as you trusted me when you brought me into your home. Many have turned me away, left me to sleep in the cold night air, frightened by what I have, frightened by my cough and blood.’ He heaved in a breath, trying to control the tell-tale sign of his illness.

His honesty was brutal and to cover her discomfort, she said, ‘I’ll heat some water. You will feel better if you wash.’

Hannah filled a pan and hung it on a chain over the fire. She pulled a cloth from a string line and placed a bowl on the table. ‘I have no man’s clothes to offer you. I’ll go next door and ask Harmina if she can lend you what is necessary.’ Her neighbour had already tut-tutted at her harbouring an unknown man. She would tut even more asking for clothes. Her Dutch friend was well aware of her circumstances; knew her brother, John, had taken off a year ago to make his fortune.

Brother! He had taken most of their late father’s savings to follow the men who cried, ‘ Fortunes for all,’ if he had the start-up money. Blinded with the promise of wealth, he had left her almost penniless. His boasting words of returning rich, dressing her in silk and buying the finest house in New York, rang hollow. Wealth had also been her father’s goal. He had sold his linen mill in Ireland to start again in the New World with cotton. He claimed it was the material of the future. She fingered her blue cotton dress, a far cry from promised dreams. Bitter resentment ran through her; she had survived scorching heat and bitter cold, been hungry more days than not. She didn’t need John, now, or in the future; she could manage well enough alone.

Gentle words washed away her thoughts. ‘I’m sorry, Hannah, I should not be here like this, but I have nowhere to go tonight. Tomorrow I will move on.’

‘No, you will not! You need food and rest.’ With the stranger asleep she could pretend normality, but with him awake an unexplainable tension filled her. She fled the room like a frightened rabbit with a ferret on its tail.

When she returned Christopher was sitting on a stool by the fire.

‘Harmina has sent you a nightshirt. After we have eaten supper, I am to sleep in her parlour tonight. They live above the bakehouse and rent all the rooms.’

As she heated a pot of what remained of yesterday’s broth over the fire, she tried not to look at him, but curiosity overcame her shyness. His face looked cleaner and he had tidied the long fair hair that touched his shoulders. His shirt was tucked into a pair of breeches, but the cotton couldn’t hide his protruding shoulder bones.

‘May I help?’

Caught staring at him she blurted out, ‘The bowls and spoons are on the shelf and the bread is in the red tin.’ Her voice sounded high pitched and strange and she cleared her throat before adding, ‘And could you fill two mugs with the ale in the clay pitcher?’

She burned with embarrassment being so close to this man as he slowly followed her instructions. She should have let him sit quietly on the stool, kept him out of her way. She didn’t know how to behave, didn’t know how to make conversation with him. The broth bubbled and she poured it into the bowls, making sure Christopher’s share was more than her own.

‘Let me take them.’

As he reached out she saw how sore and calloused his hands were. ‘After supper I’ll give you some goose grease to sooth your palms.’ She stepped aside, allowing him access to the table.

He picked up the stool from beside the bed and sat down at the table. ‘I beg your pardon, Hannah.’ He struggled to stand, using the table edge to steady himself and waited until she was seated. ‘I seem to have forgotten my manners since coming to this country.’

‘I think we have all forgotten our native manners in this savage land. Papa would say grace and then Mama would serve the meal. Please, do not apologise, just sup your broth, it will help bring back your strength.’

Christopher smiled and it changed his ill-ravaged features into a semblance of the man he must have been. ‘Yes, ma’am.’

Hannah sat in her rocking chair drinking the last of her ale. Christopher sat on a stool and seemed content to just gaze into the fire. Without warning he started to cough. He held a rag square to his mouth to smother the noise and the blood coming from his mouth. Hannah jumped up and took a clean rag from the pile Harmina had given her. As if they had an unspoken agreement he threw the soiled rag into the fire and took the one she held out. ‘Can’t you see why I should move on?’

‘I see all, but providing we burn every rag, it will be all right. When you feel better, you must sleep, and I must go to Harmina’s couch.’

‘Forget the nightshirt. Help me to your bed.’ He had become the exhausted tramp again that she had found at her door. Heer Horstman was right, only her care would see him live a few more days.

CHAPTER TWO

With the rising light of dawn, Hannah stood on the mud road outside her door, a myriad of thoughts tumbling over each other. The couch had been adequate, but she had slept little, her mind too restless with unanswered questions about her stranger. He had been right about trust. Hers had been without thought, concerned only that the man needed help. His trust had been because he had no choice. She had promised he wouldn’t die alone; what if she had failed him and it was all over? She reached out, turned the knob and opened the door. The bed was empty! Where was he! The fire hissed and a log caught a flame. Relief shot through her, he was there, sitting by the fire scraping the ash clear.

She drew a deep breath. ‘Good morning, sir, I see you have made yourself quite at home.’ He turned his head and she realised how reprimanding the words sounded. ‘I mean ... you look so relaxed and better. Did you sleep well?’

‘I did, ma’am. I woke several times but your fire gave me great comfort. You cannot know how much better your hearth is than the rising fog of the river.’

‘I’m so glad. Heer Horstman said rest and food would ...’ The unspoken words stuck in her throat again. ‘Harmina has sent a bowl of oat porridge made with milk instead of water. She said it will be good nourishment for you.’ Hannah set the bowl on the table and fetched a spoon. ‘Please, come and eat. Would you like me to help you?’

‘No!’ His voice was unexpectedly strong. ‘I must look to myself. I must not burden you with my infirmity.’ As he heaved up off the stool he staggered.

Hannah rushed to help him. ‘I think pride will most certainly come before a fall, if you do not let me assist you, sir.’ She smiled up at him to soften her scolding. ‘Tomorrow, you will be strong enough to take these steps by yourself.’

‘Thank you. Your optimism will be my guiding star.’

While he ate his oats and drank the mug of hot dark cocoa she had made him, Hannah prepared three of the precious vegetables from her store box. With a half chicken carcass she had bought yesterday it would make Christopher a more nourishing supper than last night’s meagre broth.

‘I have to go to my work in Jozef’s bakehouse. Will you sit in my rocking chair? It is far more comfortable than the stool.’ She plumped up the cushion and patted the seat. ‘Come, I need to have you comfortable before I go.’

Christopher’s features became serious. ‘I cannot stay with you, Hannah. Your reputation will be ruined having me in your home. Your neighbour cannot protect you. It is not only the sleeping arrangement; it is my seeming to live here with you.’

Hannah knelt beside him and said softly, ‘That is for me to deal with. You need warmth, food and rest. I could not live with myself if I turned you out now. I do not wish to dwell on Heer Horstman’s words, but you cannot leave.’

She cupped his face with her hands and saw the despair in his eyes. ‘Stay, Christopher, please. It will only be for a few days ...’ A sob filled her throat and she bowed her head. ‘Please?’

‘My guardian angel, how can I not when I am asked so tenderly? Help me to your rocking chair.’ Hannah did as she was bid, then took the counterpane from the bed and wrapped it over his legs. ‘Now I most definitely feel like the aging uncle being petted by an indulgent niece.’

Hannah smiled, but made no attempt to expand the subject further. She didn’t know what feelings she had. Their circumstances were unusual. Yet was she grasping Christopher’s need as a way of stemming her own loneliness? That wasn’t her intention. She was only following Heer Horstman’s advice. The Bible preached the Good Samaritan – that was her role, nothing more. ‘I will be back this afternoon. Rest well.’ She didn’t look back at him as she left.

When she returned, her basket of cakes filled the room with a sweet smell of fresh baking. Christopher sat in her chair, asleep, his face calm, his body relaxed. She had no knowledge of his circumstances, of his personal life, he had said little more than his name. Yet he had the manner of a gentleman, even though his hands were rough and sore. Right or wrong, she liked him far more than she should.

‘ Is that cakes I can smell in your basket?’ Christopher’s soft English accent broke into her thoughts.

‘ Yes. Jozef cannot sell them; they are not a good bake. So he gives them to me free to sell at the docks. Over a week, with my wage from the bakehouse, I can pay my rent.’ Shocked that she had voiced her circumstances, she hurried to say, ‘But I am helping the women who work in the docks and toil long hours. So in a way we help each other.’

‘You have a very kind soul, Hannah Rose. You deserve more than this.’ He waved his hand around, ‘Much more.’

‘My brother will return and then I shall have no need to work.’ Her defensive words of John dug deep into her like a sword. Not one letter, no matter how brief, to tell her how he fared. Bad news was better than nothing.

‘Would you like a mug of warm milk?’ There was sufficient for him. She would have hot water. It would fool her stomach and give it something to work on.

He nodded. Pity ran through her; he was too young to die. And that look of shrinking into his skeleton had returned. Even sitting in a chair was too much for him.

She sat on a stool while the milk warmed, letting the quiet room soothe her troubled thoughts. She filled the mug and gave it to him.

‘I must leave at four o’clock to reach the docks to secure my place.’ She fussed with the cakes, nervous with him and babbled on, ‘If all goes well, I should be home by eight. I’ve put a log on the fire, Harmina will come down to check on you at six and if you need anything she will get it for you, and I’ve left a jug of lemon juice and sweetened it with a little sugar –’

‘Hannah! Stop,’ he said firmly. ‘I will be all right. I promise to be here when you come back.’

‘Of course you will, where else could you find such luxury and the finest nursing in New York?’ Her light banter hid how awkward she felt. ‘I will see you later.’

She hurried towards the dock area to her selling pitch. The old hands had an unwritten rule of ‘next in line’ and she’d had to wait months to get this prime cross-roads position. A sea breeze blew inland, wafting the ever-present stink of dung and the strong smell of grain from a ship moored at a repaired wharf. This was much-needed good news to tell Jozef tomorrow. The sound of footsteps, then voices grew louder as tired, ill-clothed old men, young men, women and children filled the roadways.

A young woman waved her hand, her Irish lilt of voice soft. ‘Hannah, I’ve the sister-in-law coming tonight, make that four cakes, I can’t give her half like the rest of us. But she’ll bring sweeties for the little ones, if she can find any to buy, so I might get something back.’

Hannah placed the cakes into the woman’s sack-bag. ‘You’re a good soul, Kitty O’Rourke, enjoy your evening.’

Another familiar voice called out. ‘My usual, Hannah, my husband says if I ever pop off, he’ll marry you just to get your cakes. Me half-dozen kids come as a bonus.’ Her laugh trailed away as the woman, a child each side clutching her skirt, walked on into the maze of roads and alleyways of the East Side.

Hannah continued chatting and selling to a steady flow of regular customers until only two cakes were left. She covered them; these she would keep for Christopher and she waved her farewell to those still selling. As she hurried away, an eagerness to get home quickened her steps. There was someone waiting for her, albeit a stranger she knew nothing about.

Hannah gently opened the door. The room was lit only by the glow from a burning log that was almost spent. Christopher was lying on her bed, the counterpane draped loosely over his body. He was so still, a gasp caught in her throat. Her feet refused to move, would not take those few steps to him. Tears pricked her eyes, she so wanted him to live just one more day, one more evening to share her home and supper.

‘I’m only resting, Hannah,’ he whispered.

All was well! He was still with her. She placed her basket on the table and removed her shawl. Tears slipped down her cheeks and she turned aside to wipe them away so Christopher couldn’t see.

‘You looked so ... I mean, so peaceful ...’ Her words trailed off, ‘I mean ...’

‘I know. Come and sit with me. I’ve missed you.’

Hannah did as he asked, not able to utter a word without the tears in her throat blurring her speech. She touched his palm and felt the moisture of fever dampen her fingers.

‘Harmina came in to see me. You did not tell me she was Dutch, big and motherly. She fed me honey from a spoon and ale from your pitcher.’ His eyes had lost that dull look of yesterday and Hannah silently prayed heaven would wait another day.

‘Mrs Steiner sold me half a chicken carcass yesterday with a little meat on the bones. It simmered this morning with vegetables.’

Christopher sighed. ‘I am a burden to you. Tomorrow you must take my dollars. I must pay for your caring of me.’ His voice hardened. ‘Pity does not pay for my food.’

Hannah jumped from the stool as though stung. Her caring for him was not being done for money, it was not charity either. She had been brought up to help those less fortunate than herself. She had helped her mother for years to tend her father’s linen weavers, men, women and children, if they fell on hard times. Money was never a consideration, not ever. ‘What I do for you is because I want to, Christopher ...’ She faltered; she didn’t even know his family name. ‘You insult me. I may have asked you if you had any money to pay the apothecary, I never asked for myself!’ Anger welled up, totally unnecessary anger for such a ... what, for being practical? His words stabbed like pins into her heart. Hannah took a deep breath. ‘I’m sorry. Let us not speak of this now.’

She turned to an earthenware pot standing close to the fire and placed it on the table. ‘Will you sit with me or would you like your supper in bed?’ Now she sounded like a wife who had quarrelled with her husband.

‘Hannah,’ Christopher tried to sit up, ‘please, don’t let us fight.’ His voice cracked and he started to cough. ‘I will eat with you –’

‘No! Look what I’ve done. You will stay in bed.’

There was no argument from him. Every bit of strength used in his effort to rise. ‘Yes, Miss Hannah. I regret my words too.’

The flare of words had lasted only minutes, yet it had put her fanciful notions into reality. They were strangers, both taking what each could give.

Hannah put a bowl on a tray and went over to her bed – her bed. Not his bed. Not their bed. Lord, was she that lonely? She sat on a stool and balanced her bowl on her knees. They ate in silence until finished.

‘Angel, that’s what I called you last night. You are, Hannah, you’re my angel who will lead me to heaven.’

And that’s what these days were – a limbo of time. ‘Tell me who you are, Christopher. Give me something to remember you.’

‘Who am I? My name is Christopher Forsythe. I am twenty-seven years old, of English descent. I came to the New World to seek my fortune – a fitting epitaph for my grave.’ There was no malice in his tone, just straightforward fact.

‘Do you have any family?’

‘Family, Hannah?’ This time he laughed, ‘Oh, yes, most definitely.’

His answers were brief and not to her liking. ‘Where in England do you live? Do you live in the town or country? Why didn’t you go home, go back to England?’ Hannah thought he was not going to answer.

Then he shrugged. ‘Pride, failure and a sea journey I would not have survived. It is best my bones lie in the soil of America.’ He put a finger to his lips. ‘Now it’s your turn, Hannah.’

‘You haven’t really told me anything. Why? Have you something to hide?’

‘I’m just someone who came and will be gone – a nobody.’

‘If you exist, you are somebody.’ This time he put a finger on her lips.

If he was so secretive, why should she tell him anything? But she had started this questioning, and, being quite brutal, he would take her words to his grave.

‘My name is Hannah Rose Dudley. I was born in England and baptised into the English church. My father took his family to Ireland where he owned a mill and manufactured linen. He said, “Times were a changing.” He sold the mill because he believed cotton was where his fortune could be made. Tragically, both my parents died of the fever on our voyage to New York. My brother is a fool, be he dead or alive. And that, sir, is my twenty-three years in a nutshell.’

Christopher’s face actually coloured, wiping the pallor away. ‘So this is the life he left you. No family, no protection. You work like a servant. This is wrong.’

‘I am quite able to look after myself. Please, do not let us quarrel again.’ Every word he said was true. She was a woman alone, living in the East Side of New York in a hell-hole of all nations who spoke a babble of tongues. Thieves and murderers ran riot without retribution. Defiantly she said, ‘My brother will return.’

Christopher took her hand and rubbed her palm. It was soothing for all the roughness of his calloused skin. ‘You are a very brave young woman, Hannah Rose.’

Brave or foolish, she had no choice. Money was her driving force, without it she would end up in the doorways with men.

Christopher didn’t let go of her hand. ‘How did you survive through the great storm?’

‘The evening of the storm is one part. How we are repairing and rebuilding the city is another.’

‘Can you bear to retell me such a terrible night?’

‘I don’t want to remember that day. It brings back such terror inside me.’

‘Then, my dear, don’t. I should not have asked such a thing of you.’

‘But I will, Christopher, for I will think myself a coward if I do not.’

He went to answer, but Hannah raised her hand.

‘The weather had been wet, windy and thunderous for two days. Then on that Monday afternoon, the third of September, the air became thick and cloying. At four o’clock I was preparing to go to the crossroads. The sky was a dark moving creature, driven by a roaring wind that pounded on my door and the rain lashed at the window. As one, the storm increased to a crescendo, a roaring voice that h

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...