- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

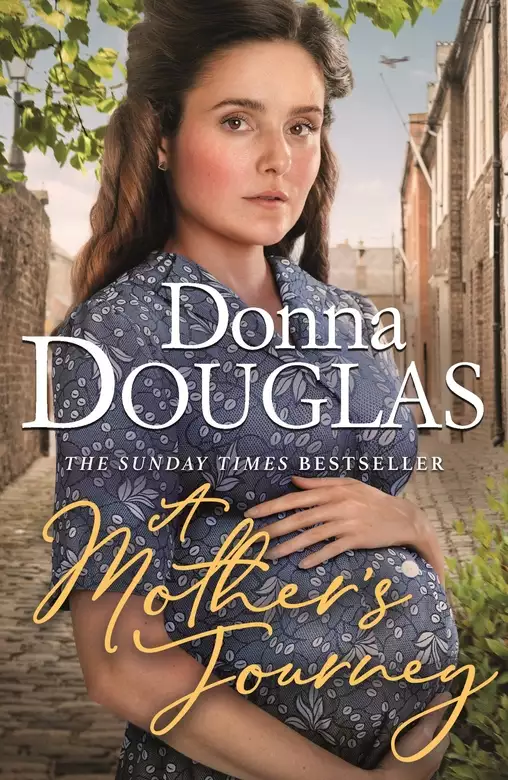

*FROM THE SUNDAY TIMES BESTSELLING AUTHOR OF THE NIGHTINGALE SERIES*

A dramatic and heartwarming new saga series from the well-loved Donna Douglas, this will be one of Orion's biggest launches of 2020.

Hull, 1940. Edie Copeland has just arrived on Jubilee Row, carrying a secret and a heavy suitcase. She left York and her job at the Rowntrees Factory after tragedy struck to make a fresh start, but she's a stranger to this street, and her fellow tenant doesn't hesitate to remind her of this, widow or no.

Luckily, the neighbours are a little more welcoming and Edie is soon made to feel at home by the Maguires and the Scuttles. As air raids sound, and the war feels closer than ever, the community has to stick together. But Edie is hiding something, and she doesn't know how much longer she can keep it up.

Is the past going to catch up with her? And will Edie still be able to call Jubilee Row home when the truth comes out?

For fans of Dilly Court, Rosie Goodwin and Katie Flynn, this is the launch of a new series based around the true stories of the Blitz.

Release date: February 20, 2020

Publisher: Trapeze

Print pages: 272

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

A Mother's Journey

Donna Douglas

1940

It was Big May Maguire who saw her first.

It was a bright, sunny Thursday afternoon at the end of June, the day after the Luftwaffe dropped their bombs on King George’s Dock. Heat reflected off the cobbles of Jubilee Row, making the air shimmer. Front doors and windows were thrown open, and children sat in huddles on the kerb, too hot even to play.

May was working alongside Beattie Scuttle, braiding a net together. They often worked outside when it was fine, to save all the hemp dust getting in the house but also because it meant they could exchange gossip and keep an eye on what was going on in the street.

May’s daughter Iris, who lived next door to Beattie, was on her hands and knees, donkey stoning her front step in a desultory fashion. From time to time she stopped to wipe away the perspiration that trickled down her face.

This afternoon, as May and Beattie handled their twine, needles and spools, they were discussing what they would do when Hitler’s troops invaded.

‘It’s only a matter of time, Pop reckons,’ May said. ‘Now France has fallen, he says we’ll be next. I’m surprised they haven’t landed already.’

‘I’ll be ready for ’em,’ said Beattie, not looking up from her work. ‘I’ve got all my bankbooks and papers in my handbag and a bag packed under the bed, ready to go.’

‘Go where, though?’ Iris sat back on her heels, pushing a stray lock of damp dark hair back under her headscarf. ‘Archie! Keep an eye on your sister,’ she called out to her eight-year-old son, who was playing with his cousins at the top of the road.

‘Our Lil says I can stay with her in Stockport.’

May glanced at her daughter. Her slight smile told her they were thinking the same thing.

‘And you reckon you’ll be safe over there?’ Iris said.

‘What are you talking about, Iris?’ May turned on her in mock outrage. ‘Of course she’ll be safe. It’s Stockport, in’t it? Jerry will never think of going over there.’

‘You’re right, Ma,’ Iris joined in. ‘I mean, how will they ever find it? Especially with all the street signs taken down?’

Beattie looked from one to the other, very cross. ‘I might have known you two would make fun,’ she snapped, as May and Iris roared with laughter. ‘Go on, then, since you’ve got all the answers as usual.’ She paused to rub away a splinter in her thumb from the coarse sisal twine. ‘What are you going to do when the invasion comes, May Maguire?’

‘I’m not leaving Hull, that’s for sure.’ Hessle Road was the only home May knew. She had grown up overlooking the fish docks, seeing the tall masts of the trawlers from her bedroom window. Her father and her brothers had been fishermen, as were her husband and her sons.

And Jubilee Row had been her home for all her married life. She had first set up home at number sixteen as a young bride, forty years ago. Her children and their families had settled here, too. Her grandchildren now played on the cobbled street, just as her own five bains once had. When the Germans finally came, at least they would face them together.

‘It’s all right for you,’ Beattie said. ‘You’ve got a husband to protect you. God only knows what those Germans will do to a poor widow like me . . .’

May cackled. Beattie was nearing sixty and as scrawny as an old chicken. ‘You should be so lucky, Beattie Scuttle!’

Beattie looked offended. ‘You can laugh, but I’m telling you, you hear all sorts—’

But May was no longer listening to her. Her gaze had shifted past Beattie, towards the top of the street.

A young woman was coming down the street towards them, staggering under the weight of a heavy suitcase that was nearly as big as she was. Her slight figure was huddled in a heavy black overcoat, in spite of the heat. Brown curls poked out from under a black felt hat.

‘Who’s this, I wonder?’ May said.

Beattie glanced up from her work. Iris stopped her scrubbing and the three of them paused to watch the girl dragging her suitcase down the street. She was young – barely twenty, May would have guessed. Although the frown between her brows and the grim set of her mouth made her look older.

‘She must be mafted in that big coat,’ May said.

‘She in’t local,’ Beattie Scuttle declared. ‘I can tell you that now.’

As if to prove her point, the young woman paused on the other side of the road and took out a scrap of paper from her pocket. She studied it for a moment, then looked up and down the terrace, scanning the line of front doors.

‘Are you lost, lass?’ May called across to her.

The young woman looked up, startled, as if she had been roused from a dream. At first she did not reply, then she called back:

‘I’m looking for number ten.’

Beattie was right, she wasn’t local. Her accent was from further north – York, or Harrogate perhaps. But that coat was too shabby for Harrogate.

‘That’s the one, with the polished brass knocker.’ Beattie pointed it out. ‘But you’ll get no answer if you knock.’

‘Thank you.’ The girl put the scrap of paper back in her coat pocket.

‘What’s your business there?’ Beattie called out.

The girl regarded her with a cool expression. ‘That’s my business,’ she replied, then picked up her suitcase and began dragging it down the street.

Beattie turned to May, her pale eyes bulging with indignation. ‘Did you hear that? I was only trying to be friendly.’

Big May laughed. ‘You were being nosey, as usual.’

Beattie ignored her and threw a scowling look back at the young woman. ‘She in’t going to get far in this street with that attitude, I’m telling you that.’

‘I wonder if she’s visiting?’ May said.

Beattie raised her brows. ‘Now who’s being nosey?’ She shook her head. ‘I doubt it. Since when did she ever get visitors?’ She nodded towards number ten.

‘That lass is a widow,’ Iris said quietly.

May and Beattie both turned to look at her. ‘Oh, aye?’ Beattie said. ‘And what makes you say that?’

‘I can just tell.’

Of course you can, May thought. Iris had lost her own husband Arthur not a year since. Even though she made a good show of getting on with her life for the sake of her three children, May could still see the raw pain of grief behind her daughter’s smile. It was only natural that Iris would recognise another woman’s suffering.

‘Happen she’s moving in?’ Beattie’s voice broke through her reverie. ‘Those upstairs rooms have been standing empty six months since.’

May Maguire turned her gaze to number ten, the only house on the street whose front door remained firmly closed, in spite of the heat. Thick lace curtains shrouded the windows.

‘God help her if she is,’ she said.

Chapter Two

Edie Copeland was aware of the three women watching her every step as she dragged her suitcase up the cramped stub of terraced houses. One was as tall and broad as a man, the other thin as a whip, both dressed in faded flowery pinnies, their heads wrapped in scarves. They were working together on some kind of heavy net that hung from a rail over a window frame. But the flat wooden needles were idle in their hands and Edie could feel their stares burning between her shoulder blades.

She should not have been so sharp, she thought. This was her new home, her new start. She was supposed to be fitting in, making friends not enemies. But her secrets had made her guarded, wary.

She reached the front door of number ten and turned to look back at the women, ready to give them a smile. But they abruptly turned away from her, going back to their work with disgruntled expressions. Only the younger woman gazed back at her with a sympathetic little smile before she turned and went on with her scrubbing.

Edie put down her suitcase and paused for a moment to massage the life back into her cramped, sore fingers. As she did, a flash of movement behind the lace curtains caught the corner of her eye. But when Edie looked again, it was gone.

She fumbled in her pocket for the key the landlady had given her. But before she could find it the front door suddenly opened and a voice from the shadows within said sharply, ‘Come in, then, if you’re coming. And take off your shoes, I’ve just done this floor.’

Edie dragged her suitcase over the front step and found herself in a narrow, tiled hallway. The overpowering smell of carbolic soap and furniture polish made her eyes water.

An elderly woman stood before her, very upright, her narrow shoulders pushed back. She bristled with severity, from her old-fashioned tweed skirt and twinset to her greying hair, scraped back so tightly it drew her skin taut over her bony face. Her pale-blue eyes fixed on Edie through thick, horn-rimmed spectacles.

She did not look too friendly, but Edie was determined to win her over. She smiled and held out her hand. ‘You must be Mrs Huggins? I’m Edie—’

‘I know who you are.’ The woman pointed to Edie’s feet. ‘Shoes,’ she barked.

Edie bent to unbuckle her shoes, aware of the woman watching her. So this was the famous Patience Huggins, she thought.

Mrs Sandacre the landlady had warned Edie about her when she handed over the keys. ‘They’ve been renting the downstairs rooms since my aunt owned the house,’ she had said. ‘He’s a nice old soul, but she – well, let’s just say she can be a bit – difficult.’

But that didn’t concern Edie. After twelve years of living with her stepmother Rose, she could put up with anything.

Besides, beggars couldn’t be choosers. She was lucky to find anywhere she could afford.

She was about to take off her coat, then saw the way Mrs Huggins was scrutinising her and thought better of it. Instead she picked up her shoes in one hand and her suitcase in the other and headed for the stairs.

‘By rights, this passageway is ours, seeing as it’s on the ground floor,’ Patience Huggins said, following her down the hall. ‘You’ll have to use it to go to and from your rooms, of course, but I’d appreciate it if you didn’t dawdle, or make a mess. And be careful of the paintwork—’

‘I’ll do my best.’ Edie turned and found herself nose to nose with the old woman. Patience Huggins obviously meant to follow her up the stairs.

‘I think I can find my own way,’ she said.

‘Oh, but I—’

‘Thank you for your help,’ Edie cut her off firmly. ‘I’ll let you know if I need anything.’

Another bad impression I’ve made, she thought as she dragged her suitcase up the stairs, bumping it up each step, still aware of Mrs Huggins watching her from below. But this time she didn’t care. After living with her stepmother she could recognise a bully when she saw one. And she was determined not to put up with it again.

Besides, she longed to explore her new home on her own. It was the first time Edie had seen the lodgings. She had been so desperate to find somewhere to live, she had taken the rooms as soon as Mrs Sandacre offered them to her, without even bothering to view them.

Now she was surprised at how small her new home was. Just two rooms: a cramped little kitchen at the top of the stairs, then a larger bedroom-cum-parlour at the front overlooking the street. As Edie opened the door, an overwhelming odour of musty damp and old age wafted out to greet her.

She pulled back the limp curtains and opened the sash window. Dusty beams of sunlight fell on the threadbare rug, the dark wooden bed, the chest of drawers and the two worn armchairs flanking the tiny fireplace. The wallpaper was yellowed with age, its faded flowers barely visible. Even with the June sun streaming through the glass, it all seemed dark, unloved and unwelcoming.

Edie lay back on the bed. The lumpy horsehair mattress barely yielded under her weight.

She suddenly felt bone weary, her limbs too leaden to move. She knew she should get started on her unpacking, but she did not have the strength.

She stared up at the ceiling. The plasterwork was yellowing, crazed with cracks. As Edie watched, some tiny black bugs emerged from one of the cracks and made their way unsteadily towards the light fitting. Outside, in the street, seagulls wheeled shrieking past her window and a distant factory hooter sounded.

So this was it. Her new start.

Oh Edie. What have you done?

She always was too impulsive for her own good. Perhaps she should have stayed in York, found a place to live there. At least she knew the city, she had friends there. Here she knew no one.

This was Rob’s city, the place he had called home. Edie had never even visited. Rob had promised to bring her here, but there had not been time before he went away.

Now he would never show her around. She was all alone.

No, she corrected herself. Not all alone. She slipped her hand inside her coat, feeling the slight swell under her cotton summer dress.

How long before she started showing, she wondered. At the moment it was her secret, but in a couple of months she would not be able to hide it under her coat so easily. Everyone would know.

And what then?

Perhaps she should have been honest with the landlady, told her she was expecting. But then Mrs Sandacre would not have let the rooms to her, and she desperately needed a place to live.

She’s going to find out sooner or later, a small, insistent voice needled at the back of her mind. You can’t hide it forever. Especially not with that nosey old woman downstairs . . .

Edie pushed the thought away. That was a worry for tomorrow. She had enough on her mind for now, without looking for anything else.

Like how to make ends meet. She had very little money, except for a few pounds she had managed to save in the post office. She had enough to pay her rent and bills for a couple of months, but after that . . .

Irresponsible, that’s what you are. How on earth do you think you can bring up a baby?

Her stepmother’s sharp words rang in her ears, unleashing a wave of despair. Rose was right. It was irresponsible to take on lodgings she could barely afford in a city where she knew no one. Edie had no job, no friends, nothing familiar to cling to, and a desperately uncertain future ahead of her.

You’ll make a mess of it, you mark my words. And you needn’t think you can come crawling back here when you do. If you ask me, the best thing you can do for that child is to get rid of it . . .

Edie sat up sharply. This wouldn’t do. She had to keep going, to stop herself thinking, otherwise she would be lost.

This was her new start, and she had to make it work. She simply had no other choice.

She hauled her suitcase on to the bed, unfastened the clasps and threw it open.

She did not have very much with her. She had pawned most of her good clothes. She hung up the few things she had in the wardrobe, trying not to notice the smell of damp wood and mothballs that assailed her as soon as she opened the doors.

At the bottom of the suitcase was a small wooden jewellery box. Edie had no jewellery to speak of, except for her wedding ring, but the box contained her treasures, as she called them.

Don’t open it, a small voice whispered inside her head. Edie picked up the box and went to put it in a drawer but at the last minute she couldn’t resist lifting the lid to look inside.

Immediately the dull gleam of Rob’s pocket watch caught her eye. It had arrived three days ago, sent from a military hospital by one of his injured comrades. One of the lucky ones who had made it home from Dunkirk three weeks earlier.

Rob would have wanted you to have this, he had written. He loved you with all his heart.

Her fingers closed round the watch tightly, as if she could somehow feel the warmth of him through the engraved metal.

Underneath the watch was a newspaper clipping from the Hull Daily Mail. Rob’s friend had sent that, too. Edie felt a tiny jolt at the blurry photograph of her darling Rob, smiling and handsome in his RAF uniform, underneath the headline, ‘More Hull War Casualties’.

Casualties. It made it sound as if Rob was laid up in hospital somewhere, waiting to come home, instead of lost over France.

Edie smoothed out the clipping in her lap, smiling at the photograph. She did not need to read the words, she already knew them by heart:

The death on active service has been notified of Flight-Sgt Robert Copeland, aged 25 of Gypsyville. He leaves behind a wife.

Not just a wife, Edie thought, her hand resting on her belly again. Rob had been so looking forward to being a father. His joy had overcome all Edie’s fears and misgivings.

How she wished he was here now to reassure her that everything would be all right.

As she placed the watch back into the box her fingers found the seashell her father had brought her back from Scarborough. She was ten years old and had been looking forward to going on the day trip for ages. But at the last minute Rose had decided she had been naughty and had to stay at home as punishment. Her father had pleaded Edie’s case, but as usual, Rose had got her way.

Edie put the shell back in the box with the clipping and Rob’s watch, snapping the lid shut. There was no point in dwelling on memories, good or bad. She had to keep looking forward, or else she would give up.

She was about to close the suitcase when she spotted the envelope tucked down the side. Edie took it out, read her name written on it in her father’s handwriting, and her heart leapt. It had only been a few hours, but she already missed him dreadfully. Their parting had been so sudden, so harsh, there had been so much she wanted to say to him. But it was difficult with Rose standing there, watching them with her narrowed, jealous gaze as usual.

But her father had cared enough to smuggle a letter to her. Edie ripped it open, her hands shaking in anticipation. She couldn’t wait to read it, to feel warmed and reassured, to know he still loved her, that in spite of Rose’s best efforts he would always be there for her . . .

Inside was a five-pound note and a scrap of paper hastily scrawled with just two words:

I’m sorry.

The words slapped her in the face. Edie looked down at the money in her hand. She knew it was his way of saying goodbye.

She stuffed it back into the envelope and threw it in a drawer. Stiff pride made her want to send it straight back to him, to hurt him as she felt hurt. But deep down she knew pride was a luxury she could no longer afford.

Edie took a deep, steadying breath. She couldn’t afford to give in to self-pity. She had made a promise to Rob to make a home for them, and she meant to keep it.

‘Find a place for us,’ he had said to her. ‘Somewhere we can be together, the three of us. Then when all this is over I’ll come home to you, I promise.’

She pressed her hand to her belly. ‘It’s just the two of us now,’ she said aloud to the empty room. Rob might not be able to keep his promise, but she still meant to keep hers.

Chapter Three

‘It won’t do,’ Patience said, scrubbing at a grease spot on the wooden counter. ‘I don’t know what Mrs Sandacre was thinking of, I really don’t. Horace, are you listening to me?’

‘Yes, dear.’ Her husband’s weary voice came from behind his newspaper.

‘I mean, we know nothing about her,’ she went back to her cleaning. Her shoulder ached from scrubbing, but she was too agitated to stop. ‘Who is she? Where has she come from?’

‘Happen you might know a bit more about her if you hadn’t bitten off her head the minute she walked in,’ Horace mumbled from behind the newspaper.

Patience balled up the cloth in her hands and fought the urge to throw it at him. At least it might get his attention. There was no talking to Horace these days. If he wasn’t reading the news in the paper, he was fiddling with the wireless, trying to find the news broadcasts. He even listened to the German stations giving out the names of the captured soldiers every night.

‘And she’s so young. She looks – lively.’

‘It might be nice to have a bit of life about the place,’ Horace said mildly.

‘A bit of life?’ The tightness in her throat made her voice shrill. ‘A bit of life? I hope you’re still saying that when she’s throwing parties, having strangers tramping up and down the stairs, through our hall, in our back yard—’

She looked past the brown-taped windows to the back yard. Her yard. It wasn’t right.

‘Give the girl a chance, Patience. You’ve said yourself, you know nowt about her yet.’

‘I know trouble when I see it,’ Patience said darkly. ‘And that girl’s trouble, believe me.’ She turned back from the window. ‘You’ll have to talk to Mrs Sandacre, anyway,’ she said.

‘What do you want me to say?’

‘Tell her we don’t want her here!’

‘And why should she listen to us?’

‘Because – because we’ve been good tenants for nearly forty years.’

‘I shouldn’t think that will make any difference.’ Horace folded up his newspaper and nodded towards the stove. ‘Summat’s boiling over.’

Patience snatched up the bubbling pan of cabbage before it spilled and swung it over to the sink to drain. Infuriating as it was, she knew Horace was probably right. Things had been very different when Mr Sandacre owned the house. He would never have stood for any riff-raff. He had breeding. Not like his widow, renting out rooms to all and sundry.

Patience carefully transferred the drained vegetables to a china serving dish. It wasn’t her very best china, but even though there were only the two of them she still liked to do things properly.

‘That’s not the point. Mrs Sandacre should have asked us.’

‘It’s her house, she can do as she likes.’

‘That’s as may be. But it’s our home.’

‘It in’t like we haven’t shared it before.’

‘That was different. Miss Hodges was refined.’

Miss Hodges had been quiet, inoffensive and respectable. She knew how to keep herself to herself. Patience hadn’t even noticed when the old dear had quietly expired in bed just before Christmas.

Patience dumped the china dish down in the middle of the table. ‘So when will you talk to Mrs Sandacre?’ she asked, as she watched Horace ladling cabbage on to his plate. ‘I think you should go down to the rent office tomorrow. It needs to be sorted out before the weekend—’

‘No.’

She looked up sharply. ‘What do you mean – no?’

‘What I say. I in’t doing it, Patience.’

Patience stared across the table at her husband as he calmly picked up his knife and fork and started eating.

‘But you must!’ she said.

‘Why?’

‘Because – because I don’t want her here!’

Horace took a moment before he spoke. He looked back across the table at her, his jaw moving back and forth as he chewed his food.

‘I do a lot for you, as you know,’ he said finally. ‘But I won’t see a young girl put out on the street just because you’ve decided you don’t like the look of her.’ He shook his head. ‘If you want to talk to Mrs Sandacre, you’ll have to go and see her yourself.’

Patience’s gaze dropped to her plate. ‘You know I can’t do that,’ she said quietly.

‘I don’t know why.’ He pointed towards the hall with his fork. ‘There’s the front door. All you have to do is go through it.’

They faced each other across the table, and Patience saw the mute challenge in his eyes. She pushed her plate away and stood up abruptly.

‘Aren’t you eating?’ Horace asked.

‘I’ll put it in the oven and have it later.’ She seized the Vim and doused the sink in a thick cloud.

And so it began, she thought. Edie Copeland had only been here half an hour, and she was already causing trouble. Horace would never have spoken to her like that usually. He understood how she felt, that her home was her sanctuary, the only place she truly felt safe.

‘There’s something about her,’ she muttered. ‘You see if I’m not right.’

Chapter Four

The first week of July came and went and there was no sign of the Nazi invasion everyone had feared. The air-raid sirens that had moaned over the city night after night fell silent, as did the anti-aircraft guns in Costello Playing Field. Meanwhile, according to the newspapers, the Spitfires were doing their best to keep the Luftwaffe from the skies.

Sam Scuttle was digging a hole in his mother Beattie’s back garden. Iris watched him over the fence as she pegged out her washing next door. He had only been working since that morning but he was already waist deep, his vest stained with dirt, skin slick with sweat as he flung spadefuls of earth on to an ever-growing heap behind him.

‘Burying a body, Sam?’ Iris called out to him.

He paused, looking up at her with a grin. His sandy hair clung damply to his perspiring face.

‘Nowt so exciting,’ he called back. ‘Ma wants an Anderson shelter.’

‘The public shelter on the corner not good enough for her, then?’

‘It’s good enough for her, all right. But it’s our Charlie she worries about.’ Sam leant on his spade. ‘Ma has a terrible job getting him out of the house when the sirens go off. He can’t stand the noise.’

Iris nodded, understanding. Charlie Scuttle had been best pals with her older brother Jimmy. They had gone off to war together as a pair of happy-go-lucky sixteen year olds twenty-four years before. They had both returned home sadder and wiser. But while Jimmy had got on with his life, going back to work on the trawlers, getting married and having a family, poor Charlie had returne. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...