1.January 17th 1950

THAT DRATTED TELEPHONE. Always ringing when Mrs Rosen had her hands full. Here it was a quarter past eight already by the hall clock and she had half a dozen little jobs to do before taking the tea trolley into the lounge at nine. Clearing up the dinner plates always took longer than she thought it would. You’d think she’d know, after all these years, that the gentlemen travellers couldn’t help splashing their soup around, but it came as a surprise every time.

It took a moment to find a place to set down the clean tablecloth before she could answer the phone’s wheezy jangle. The lobby area was padded with winter coats – scarfs and hats jostling for space on the pegs, and more galoshes and overshoes underfoot what with the weather this week being so mucky.

The pale Bakelite phone summoned her with more of a rattle than a ring, which explained why none of the gentlemen in the lounge had heard it. Another thing that needed seeing to. Mrs Rosen managed to balance the tablecloth on a pile of magazines set out on the hall chest by the phone and note pad, and keep them from falling onto the floor with her hip while she picked up the heavy receiver and lifted it to her ear.

‘Scunthorpe 478? Yes, good evening …’ A roar of laughter greeted some successful anecdote in the lounge. ‘I’m terribly sorry, I didn’t catch that. Do you need a room? It’s two shillings a night, and that includes a light breakfast as well as dinner and tea. Oh, I’m sorry – one of our guests? No, I don’t think we have a gentleman named Cook with us … Oh it is spelled C-O-K-E? I see. Well, my husband didn’t mention a young lady, but he served at dinner, you see, while I was in the kitchen …’ She paused to let the person on the other end of the line speak. Now she straightened up smartly and the tablecloth and magazines slithered onto the linoleum floor. She barely noticed. ‘Oh yes, I see. If you would just bear with me one moment, madam.’

Mrs Rosen’s youngest was trying to scoot by, but she was too quick for him. She grabbed his collar and pointed at the fallen glossies and tablecloth. As he gathered them up, she set the receiver down with great care next to the phone, then undid the ties on her apron and hung it among the greatcoats of the travelling salesmen. Now she looked there was a lady’s coat hanging among them. A pale brown duffle coat with big wooden toggles, and a floral scarf tucked round the hood. Very pretty. She touched her hair. Jimmy gave her an odd look and she scowled at him and pointed till he got the message and took the clean cloth into the dining room.

She opened the door to the lounge. All men as far as she could see, crowded around the little tables with constantly filling ashtrays between them. Other than tobacco the air smelt dark and sharp, that hair cream the gentlemen used. The noise of conversation died down as they saw her open the door.

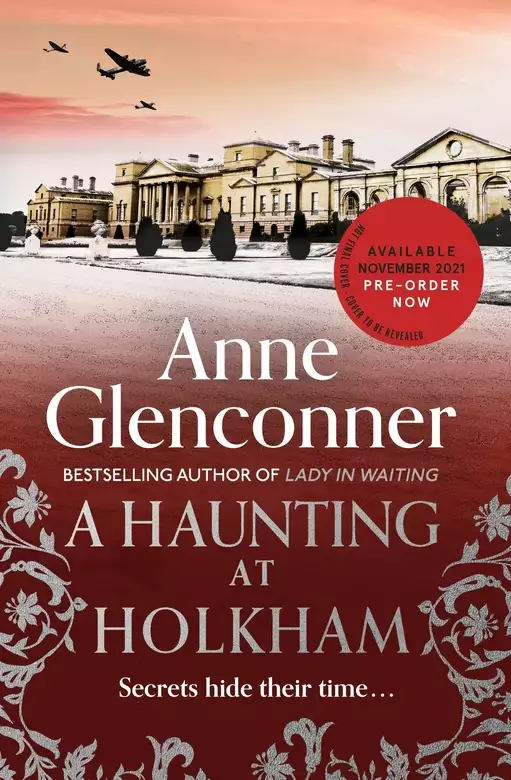

‘Is Miss Coke here?’ she asked, pronouncing it properly to rhyme with ‘book’ and still not quite believing such a person could be in her lounge, but the refined female voice on the telephone had seemed quite certain. ‘Miss Anne Coke of Holkham Hall?’

A slim arm appeared, waving above the heads of the room’s other occupants, and Mrs Rosen watched as a tall, slender young woman, a girl really, not more than seventeen, with blonde shoulder-length hair held neatly off her face and brushed-out curls, rose out from among the salesmen like a Venus rising from the foam of commerce. She was holding a book and had been sitting on the corner sofa. Her finger was trapped between the covers, marking her place.

‘Telephone call, Miss Coke. From your mother, at Holkham Hall,’ she couldn’t help adding.

‘Thank you so much, Mrs Rosen,’ the young lady said. The salesmen shuffled their chairs out of the way to let her by and stared. The ones who had spoken to her at dinner looked, slyly smug, the ones who had ignored her, profoundly disconcerted.

‘This way,’ Mrs Rosen said, and led her out of the room as if there could be any confusion as to where the telephone was. Mrs Rosen closed the door on the lounge and the men left behind stared at the closed door.

‘Holkham Hall? Isn’t that some enormous pile in Norfolk? Earl of Leicester’s place?’ a ginger-haired man who travelled in toothpaste asked the room in general.

‘On the coast and a stone’s throw from Sandringham,’ an older gentleman with an iron moustache replied. ‘Miss Coke is the granddaughter of the Earl of Leicester.’

‘No!’ Ginger said. ‘She told me her family run a pottery and she’s hoping to sell vases and Toby jugs to the fancy goods shops in Grimsby and Skegness!’

‘That’s right.’ The gentleman with the iron moustache had thought the ginger-haired fellow was a little full of himself and enjoyed seeing him temporarily flustered. ‘I do the King’s Lynn run at least twice a year. They converted the old laundry at the Hall. Nice things they are making there too, got some artistry to them. Pretty little set with snowdrops on them.’

The door opened again and the young lady returned. She looked, if possible, a little paler than she had before. Several of the men stood up.

‘I’m terribly sorry, I left my bag by the sofa. Might someone pass it to me?’

The handbag, more of a briefcase really, was retrieved and Iron Moustache had the privilege of passing it into her hands.

‘Not bad news, I hope, Miss Coke,’ he said. He had a kind, avuncular face. Anne had met him once or twice on these selling trips, and he had absorbed the news of her aristocratic lineage with calm courtesy and the minimum of fuss. He had been happy to share his knowledge of sales too – the best days to visit certain shops and who liked to chat, but never bought. Samuels, that was his name. Marcus Samuels. She swallowed.

‘I’m afraid so, Mr Samuels. My grandfather has died. I must go home at once.’

The men murmured their sympathy and concern, and those smoking put out their cigarettes as a sign of respect.

‘I am sorry to hear that,’ Mr Samuels said. ‘A very fine gentleman. And you are determined to drive back tonight, Lady Anne?’

Her blue eyes widened slightly to hear herself addressed as ‘Lady Anne’. A small thing, but it carried a great deal of change with it.

‘I feel I must.’

He nodded. ‘We shall let you pack, but I think perhaps the gentlemen here and I can come up with a list of useful numbers and a few names. A few garages and guest houses along your route in case you run into any trouble with that little car of yours. Yours is the Mini Morris, isn’t it?’ She nodded. ‘You’ll be going through Sleaford and Holbeach, I imagine. We can do that, can’t we, chaps?’

The chaps were quite sure they could.

‘That’s very kind.’

‘A pleasure, my lady,’

‘Thank you so much,’ she said, hardly knowing what she was saying, then she withdrew to speak to Mrs Rosen and gather her belongings.

‘I see it now, of course,’ Ginger said. ‘Breeding.’

Mr Samuels sniffed meaningfully and took his notebook out of his pocket.

‘Right, gentlemen. Let’s make sure Lady Anne gets home safe.’

Anne went to her room and began to pack her few odds and ends into her suitcase. The case with her samples from the pottery, carefully wrapped in sheets of newspaper, was still in the car. Then she sat down rather suddenly on the narrow bed, her wash bag on her knee.

‘Oh, Grandpa!’

A fall, her mother had said on the telephone, he had missed his footing on the cellar stairs between the chapel and the gun room. How could he have done? He knew every stone and step in Holkham, every brick and polished flag. Had her mother said something about a stroke? Wasn’t Grandpa too young for a stroke? He was not even seventy yet. He had only become Earl in 1941 when his own father died at ninety-three. Anne had thought of him as in his prime and he had seemed quite well when she left Holkham three days ago. He was enjoying the tail-enders, getting the best out of the last weeks of the shooting season and filling the game room with pheasants, while Anne, her sister and her mother worked in the pottery opposite. They charted the progress of their own days by the sound of the guns, the distant thunder from the coveys around the kitchen garden.

She saw her tears had fallen on her leather wash bag and wiped them off before they stained. And Dad was the Earl now! Already! He would be in an awful state. He had become so nervous since the war, everything had to be just so, as if not arriving for dinner on the stroke of eight meant the entire house would collapse around their ears. Now there would be another round of death duties and that would drive him potty. But worse than all that, what would the house be like without Grandpa in it?

Anne lifted her head. Whatever had happened, whatever did happen, sitting here wouldn’t help matters. She stowed her bag and hair brushes, pyjamas and stockings and clicked the case shut, picked up her briefcase and carried them both downstairs to collect her coat, scarf and the condolences of her fellow travelling salesmen.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2025 All Rights Reserved