The first power was nature. In humanity’s infancy, power was not yet ours to hold. Laws and forces beyond human comprehension shaped our lives, and everything we did was aimed at survival.

The second power was spirit. Incomprehensible forces took on form and personality. We struggled to comprehend their whims, and power was born from divine approval.

The third power was law. We decided what we thought right, and set principles above any king. Power became at last a human thing.

The fourth power was money. The forms we built took on life of their own, and the power we created escaped from our grasp and devoured us.

The fifth power is nature. We understand the wisdom in the forces that first shaped us, but now we adapt to them, learn from their patterns, and dance with them. Power is ours, but not ours alone, and we can create harmony with the world.

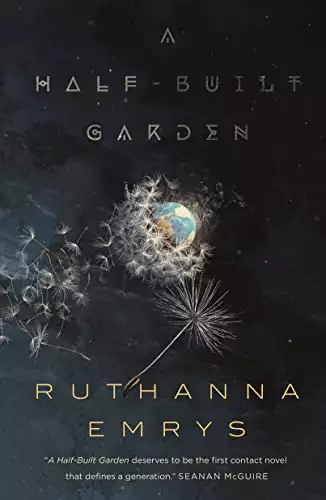

—from The Dandelion Manifesto, v.2.3, released December 2043

In the bad old days (the commentary said later), nation-states had plans laid in for this sort of thing. They’d have caught the ship on satellite surveillance. They’d have gotten in the ground with sterile tents and tricorders and machine learning translators, taking charge. In a crisis, we still look for the big ape. But the view from below has long since supplanted the view from above, so there were no satellite pictures committed indelibly to collective memory. Instead, the embedded water sensors near Bear Island suddenly sent out alerts for skyrocketing phosphate levels. And instead of a big ape shouting orders, the world got me.

It was 3:22 a.m. on Monday, March 2, 2083, and I was on call for sensor events along with eleven other volunteers for the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Network. I was first in the ground, even though our consensus judgment of the reading was malware noise, because I was already up with Dori. She’d been awake and crying for well over an hour, and I almost cried myself at the excuse for a handoff. I woke Carol with truly sincere apologies—but I had to go check out a Watershed emergency, see if you can get this baby back to bed.

If it’d been ten degrees colder, she wouldn’t have bundled Dori into a sling and come out with me, and this would’ve been a different story. But the kid quieted down as soon as we stepped out onto our walk, and I admitted that there probably weren’t really dangerous pollutants on site, and if there were my wife and kid could stay back. The night was balmy and smelled of lilacs. The illumination curfew had kicked in, and stardust stretched across the old Maryland suburbs like a parade scarf. My mesh asked me if I wanted night vision, and I told it quietly to fuck off.

“In a couple of months it’ll be too hot to take her outside most nights,” said Carol, and we held her up to the moon, and snuggled her against our chests, and she fell asleep in the car seat of the Watershed-sponsored ride as soon as it started moving.

“You will reach your destination in twenty-eight minutes,” the ride told us, and we looked at each other and at the baby, and then slept happily in each other’s arms the whole way.

At the drop-off Carol took the sling and managed to shift Dori without waking her. Then we walked across the bridge and picked our way along the path—I didn’t turn on night vision, but I did up the tactile gain in my soles—all the way to the north-side cliffs. And there we found a palace, where before had been only root-cracked stone.

Silver, I thought at first, gleaming in the moonlight. But I blinked and saw black metal with the iridescent sheen of a grackle. Human eyes weren’t made for it. When I toggled my lenses to night vision, the palace shed a rainbow of heat across the budding clover.

I messaged the network: Not a false alarm. Not a spill. Need more sensors. I wasn’t sure what else to say, or if sending a picture would get me accused of snoping. Hell, I wasn’t entirely convinced the thing would show up on-screen.

“You see that?” I asked Carol, nervous until she nodded. She wrapped her arms around Dori.

“Palace” was the closest word I could find, and it wasn’t very close. It was a quarter-acre spread of spires and domes, fractal at the tips, narrow peaks spiraling in intricate patterns. It sloped down from three larger promontories, swooping at the edges as though it wasn’t quite ready to meet the ground. It ticked softly, like a cooling pan. As I watched, part of it seemed to fold in on itself, and then out again showing a different design. Then another, and after that another, and I realized that it was constantly renewing itself one section at a time, a shifting landscape mesmerizing as a sunset.

Dori shifted and murmured against Carol’s chest. I scanned for radiation, let out a breath when I found nothing worse than background.

“What are they dumping in the water?” Carol whispered. “And why?”

I queried the sensors again. “It’s tapered off, but we’re still getting weird organics.” Whatever’s in there, they make waste. And dump it.“It’s not just a bot probe.”

I thought of old movies: people approaching spaceships with their arms wide in welcome, incinerated by lasers. I should go home. I should send them home. But my breath came fast and short, like the moment the midwife had placed Dori in my arms, like the first time Carol’s lips brushed my ear. I wondered if a thousand of these things were dropping across the world, or if this was the only one. I imagined telling Dori, years from now, that we could’ve met people from another planet, only we were trying to protect her. Or we could stay—and tell her that she met them.

I gripped Carol’s hand. We shared a look, a nod, and I leaned briefly against her, grateful for unspoken agreement. Some things are more important than keeping your kid safe.

Screw being too nervous to tell anyone, though. Whatever risk we took for ourselves, we owed something to the rest of the world. I started my lenses recording, fed the livestream into the network. I flicked from ordinary vision to heat to electromagnetism, sending all the data I could gather. On that last setting I caught a darker patch near the palace’s center. I tried heat again, increasing the sensitivity. The same section showed cooler, spring green where the rest burned orange and yellow.

“Something’s broken there,” I told Carol. Confidence faltering, I added, “I think. There’s a cool patch, sort of jagged, and not in a symmetrical way.”

“It doesn’t look like it crashed. Are they sending out, I don’t know, some sort of distress beacon?” She stopped. “Maybe the organics area distress beacon?”

I started giggling. “Help! Poop!” I’m sorry, I know this isn’t the sort of quotability people look for in historical events. But Carol started laughing too, and neither of us could stop, and then Dori woke up and started crying and we froze. There are humans who get vicious when they hear a baby wail. But no lasers burned out to shut us up. I tapped my mesh to view the diaper monitor. “Guess what?”

“Distress beacon?”

What was I supposed to do? Carol unhooked the sling, and I laid it down on the chilly grass, and I changed Dori’s diaper right there in front of an alien artifact of unknown origin. I hoped Carol was wrong about the organics, because I wasn’t quite willing to try a urine-soaked pad of smarthemp as our first communication attempt.

“Are you still recording?” asked Carol.

“Yep. This is for posterity.” We switch off after diaper changes, so I pulled on the sling, adjusting it for my thinner shoulders, and cuddled Dori. “Hope you’re appreciating this, posterity.”

Carol isn’t obsessed with sensory extension the way I am, but she knows every type of communication technology there is and she’s always happy to help brainstorm. “Okay, assuming they don’t talk to each other through effluent streams, they obviously know enough about our signals to find an uninhabited spot close to a big city. Are they sending anything that looks like a phone signal? Dandelion network encryption? God help us, wifi?”

“I’ll look.” I started scanning, frequency by frequency and format by format. Meanwhile our own network was starting to wake up. When I checked messages—automatic reflex even now—I found the anticipated accusations of snoping, but also suggestions for signal searches, and full files of every message humanity had ever posted out to the silent stars. I added a tick to the ongoing vote over whether to share with other watershed networks. People needed to know, and we needed the support.

No phone signals. No local network—at least not on any familiar frequency. I worked all the way down to radio before I found it.

It wasn’t only radio, but sound, transmitted the same way we do it, the same way we’ve been doing it for almost two hundred years. They’d picked an empty bit of spectrum just below the NPR legacy transmission. I gave up on the limited bandwidth of lenses and earrings, and passed the signal to my palette. The speaker blared.

“It’s music,” said Carol.

“Human music.” Drums and trumpets finished with a grand flare. A simpler melody began, a series of electronic tones that ran in a loop, dah-dee-dah-bum-bum.

Are you getting this? I sent to the network. We need to identify it.

Could be a stand-in for an equation, suggested someone, and within a minute the board had branched into three teams: music folks, math folks, and everyone else speculating wildly about other possible meanings. The tone series faded, replaced by singing, high and fast and soaring.

The third group burst into excited activity. Gujarati, that’s Gujarati, someone connect with the Ghats-Narmada network now!

Then the music group: It’s Bollywood. Sounds like something from a couple decades ago—hold on, I know a database for that, if my old log-in works.

Dori yawned, blinked, and swiveled toward the music. “Bop!” she announced.

“Bop,” I agreed. “Carol, what are they playing this stuff for? Why a movie soundtrack?”

“Showing off their good taste?”

The Chesapeake network exchanged handshakes with Ghats-Narmada (where everyone was awake and in work shifts, but no longer working), and hurriedly navigated the protocols to affirm that yes, this was worth the contagion risk. The antivirus icon flickered in the corner of my lens as our network filtered out a dozen minor infections, well within its immune response. A minute later, the answer came through.

It’s an obscure science fiction movie from the 60s. Beyond the Clouds of Dust—this is the theme when the spaceship arrives.

Carol and I stared at each other, and about thirty people posted in unison: IS IT FRIENDLY?

Yes, they share this weird healing potion, and there’s a really cool three-way interspecies love story.

Dug up a match for the first one, said someone else. It’s from a radio play about alien refugees in Brazil.

The music changed again. “I know that one,” exclaimed Carol. “That’s one of Dinar’s old anime series—and it’s another one where aliens are friendly—I mean, the ones who have that song as their theme are friendly, there are about five others—”

I found that second one! It’s an American film from over a century ago, and it’s what the aliens play to introduce themselves. And yes, they’re friendly.

“We come in peace,” I said. My voice sounded too loud, or maybe too quiet. “They’re saying they come in peace. And they want to talk.”

That would have been a good time for cynicism—for someone to ask if we believed them, or if their definition of peace looked anything like ours. But no one wanted to spoil the moment of joy. We didn’t want to play nation-style realpolitik, or be properly mature and suspicious. We wanted to talk.

However complicated things got afterward, I still can’t regret that.

“Carol,” I said. “Weren’t you working on a radio transmitter for your sweater swarm? Could we mod that to send a response?”

“Yes, but I didn’t bring my sewing kit, I brought the diaper bag. Maybe Athëo and Dinar could drag it over? Or we could ask the network if someone nearby has one.”

Already in it, came a network response, while Carol was still trying to work out a plan with our co-parents.

“They don’t want to wake up Raven,” she said. “It’s one thing to come out here with Dori and find—” She waved at the palace.

“But another to wake up a toddler with a runny nose and bring them someplace you know might be dangerous, yeah.” Even if Raven, at almost two, was more likely to appreciate the experience. But Athëo and Dinar had only moved in a month before Dori was born, and Raven was just learning to call us Mom and Eema; it wasn’t our decision to make.

I bounced on my toes, jiggling Dori and shaking out my nervous excitement. I watched the network traffic as people arranged to bring in a radio transmitter, more sensors, a better sample kit than the one I’d packed for basic nutrient protocols. I tried to think of something to do in the meantime.

“Do you think they can see us?” I asked. I tried to imagine how we’d look to an observer who’d never met humans before. Two hairless primates standing side by side, one carrying an infant. Would they notice that Carol was taller and broader across the shoulders, or that my eyes were brown where hers were hazel? Would they even be able to separate us from our tools: understand that my denim and Carol’s cotton dress were clothes rather than skin, that Dori’s infant curls were part of her while the smartmail mesh helmeting our adult scalps came off at night?

“We don’t even know if they have eyes,” said Carol. She hugged me, and I realized that I was shivering in the clear winter night. Her touch brought the world beyond the palace back into focus: the bare-limbed maples and pawpaws, the dry whispering grass, the splash of the Potomac against the cliffs. Dori, head resting heavy and warm against my chest. I breathed the moment of miraculous stillness, about to break against the unknown.

Amid the shimmer of the alien construct, near the base of the closest peak, something moved. I flicked back to night vision, added a standoff chemical scan. We clung more closely.

“What are we doing here?” I whispered. “We’re not qualified for this. I’ve repped the Chesapeake in carbon negotiations one time.”

She shrugged against me. I marveled at the familiarity of human anatomy, that I could read her thoughts in that little shift of muscle. “More than I’ve got, unless you count dickering over yarn and circuits. But we’re here, and no one else is. We’d better not fuck it up.”

Against the spill of warmth—eighty-seven degrees Fahrenheit, a spectrum of steam and oxygen and nitrogen and remnant volatiles—a warmer figure scrabbled. I held my breath, squinted irrationally, and upped the light gain on my vision. The creature—alien—person, that had to be the right word, stepped lightly down the side of the palace and into the rock and scrub of our world.

They were long where we were tall: a dozen narrow limbs supported a body scaled like a pangolin’s. More limbs, flared or pointed at the ends, spread from the sides of their torso back toward a broad, flat tail. There wasn’t enough light to tell color, but the shade of their scales varied, mottled dark and pale. Two large eyestalks bulged from the sides of what I decided to assume was a head; smaller sensory organs dotted the head in complex patterns and diffused down their back.

I swallowed. The realization that I was still recording, that my next sentence would be remembered for as long as humans kept records, froze my thoughts and my tongue.

The alien tucked their tail under themselves and rolled back so that they lay rocking on the curve of their own body—limbs scrabbled to sweep pebbles from beneath—and they tapped their dark belly. Small antennae or cilia covered the glistening skin there revealed. I caught my breath: clinging to those cilia were two miniature versions of the alien. One bent its head back, twisting sideways to point an eye at me. It let out a whistling warble, which the other echoed at lower pitch.

Dori twisted her own head around, lips parted in delight. “Bah!”

“That’s for history,” I told her. I knelt down to match the alien’s new height, and Carol joined me. “Welcome to Earth. What’s yourname?”

The alien brought two pairs of limbs together, drawing one across the other like a bow. Pitched oddly, but clearly comprehensible, I heard: “These are Diamond and Chlorophyll. I am Cytosine. What’s your name?”

Kids first, apparently. “This is Dori. I’m Judy Wallach-Stevens, and this is my wife, Carol.”

Music spilled from Cytosine’s limbs, that same five-note series from the initial transmission. “We understand each other!”

“Yes. You’ve been listening to us?” But of course they had: watching our movies, picking up our broadcasts, well over a century’s worth of stories and school videos and documentaries and news. What were they like, to follow all that and still want to meet us?

“Yes. That’s how we learn. You haven’t heard our songs yet, but you are far advanced and we didn’t dare wait. It’s reassuring to know you’re civilized like us.”

Wait, what? Beside me, Carol stiffened. But whatever cue had made them call us civilized, I didn’t want to admit confusion. If they were anything like humans, the other side of that line could be unpleasant—maybe even fatal.

I heard a ride door slam, and someone walking down the path. This discussion was about to get a lot less controllable.

“We’re glad to have you here,” I said at last. I hesitated, not wanting to claim unfounded authority. “I’m present for the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Network. May I ask who you’re present for?”

Simulated human laughter, drawn from Cytosine’s bowstring limbs, somehow eerier than words produced the same way. “Yes, of course. I’m first mother of the Solar Flare”—limbs pointed at the palace behind them—“here on behalf of all the families of the Rings. We can help you escape this world.”

I pulled Dori close. “Escape it? Why?” Scenarios tumbled through my mind: an incoming comet missed by our scant satellites, methane reservoirs breaching their tenuous tissue of permafrost and geoengineered shields—or Cytosine’s people teleporting nine billion people to “safety” before appropriating Earth for their own purposes.

“Hallo,” called a voice behind me. “Radio Free Terra is in the—oh, shit.” The newcomer, bearded and thickly built and wearing a they/them badge, set down a box of equipment and gaped.

“You’re late,” Carol told them. “We’re past exchanging radio signals, and on to…” She trailed off, and I wasn’t sure how she should finish that sentence either. “Cytosine, this is Redbug. They build old-style radios, like you used to send those songs.”

Probably the Solar Flare had simulated the radio electronics with some sort of advanced computer—then again, maybe they had a geek in the depths of their ship who enjoyed tinkering with circuits as much as Carol did. I pictured a beaver-pangolin hunched over a workbench, swearing at uncooperative pliers. Whether Cytosine intended threat or apocalyptic warning, their people must be as weird and varied as us. The thought kept me from spinning off into flights of panicked speculation.

But the distraction served another purpose: I posted the question to the network. If there was a comet someone could redirect telescopes; high methane readings would trigger a cobweb of dispersed sensors.

Query sent, I steadied myself. “Why do you think we need to escape?”

Cytosine curled more tightly, stroking Diamond and Chlorophyll—mirroring my embrace of Dori? “All species must leave their birth worlds, or give up their technological development, or die. You are very close.”

“Is that a philosophical statement, or are we facing a specific danger?”

Redbug glanced between us, obviously fascinated but also obviously even more nervous than I was. “I’m just gonna be over here, setting up a base station, okay?” Carol waved them toward an open patch of moss-covered rock.

Cytosine had been rocking a little—thinking? “Philosophy. And empirical observation. Species breed out into vacuum, or die amid their own poisons at the level of technology you have now.”

“All of them?” Carol had that tone in her voice, the one that caused sensible people to back up and scurry for citations.

“This is the fourth world we’ve visited after picking up signals, and the first where we’ve arrived in time.”

“Maybe because we’re doing something right?” I suggested, more sharply than I’d meant to. We’ve never done this before. Don’t fuck it up.

“Because you’re closer. Your planet is a hundred and sixty light-years from the Rings; we could build the tunnel as soon as we found your signal and arrive within the survival window. Why won’t you believe me?” That rocking again—frustration, maybe, or anger. “Your world is pushing the edge of your species’ temperature range. Your seas are scarred by barren patches. Your atmosphere is out of balance. Have you not noticed?”

“Of course we’ve noticed,” I said. “We’ve been doing something about it!”

“Worlds aren’t meant to support technological species. They’re birthing burrows, not warrens.” Their voice rose in exasperation—how closely had they studied us, to catch the melody of our language as well as the words? And what should we make of that effort?

Chlorophyll let out a high, keening cry. They didn’t sound much like a human baby—more like a miserable cricket—but the distress was unmistakable. Diamond joined in at lower pitch.

Then Dori, of course. I busied myself trying to comfort her, grateful for the respite. Perhaps that was why Cytosine had brought their own kids out? The children had diffused a tense diplomatic parlay. A few arguments at those carbon negotiations would’ve benefited from the interruption.

“I think she’s hungry,” suggested Carol. “Them too.” I saw what she meant: Cytosine’s belly glistened more brightly, and two long triple-forked tongues licked out across it. Shrugging, I pulled down the side of my shirt and let Dori suckle as well. I shivered and pulled the wrap close. Aching warmth pulsed between us, pulling me back to practicalities.

“Look,” I said to Cytosine. “Leaving aside the, the philosophy, what are you actually asking us to do?”

Limbs scraped out speech. “Leave, and join us.”

“The hell!” said Carol. I put a hand on her.

“We will share everything we’ve learned,” continued Cytosine. “We will show you how to build tractable environments, make space around your star to grow and thrive. We will show you the secrets of tunneling. We’ll make new symbioses together amid the great cloud of worlds. We will be sisters.”

My sisters don’t usually come to my house and demand I move out.“That sounds pretty exciting. What are you going to do with the Earth after we move out?”

Cytosine rocked back, eliciting squeaks of complaint. “I told you. We’re a technological species too; we aren’t meant for life on worlds.”

I took a deep breath, held Dori tighter. “And what are you going to do if we say no?”

More rocking. “I don’t know. We thought you were like us.”

At this point, I want it in the record, I pinged the network telling them that this was beyond my skill set, that we needed to identify the most experienced negotiators from every network, and that I’d try to wind things down until we could get a proper team in the ground. And the network agreed. I tried not to get too distracted by the thread traffic, which hadn’t yet surfaced any useful suggestions about what I should say, but was neck-deep in critique of what I had said.

A few more people had joined us on the island, all tech experts—they’d tracked my feed, and joined Redbug in setting up an impromptu base camp. They were swearing in urgent whispers over tent pegs and screens, arguing over equipment requirements. It looked gloriously restful and easy. Coral light etched the river, and I’d gotten about two hours of sleep. Exhaustion muffled my reactions. Once I’d had a chance to nap, surreality would give way to awe, or terror, or the paralysis of fully understanding what I’d done. But by then, I hoped, it would be someone else’s job.

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved