- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

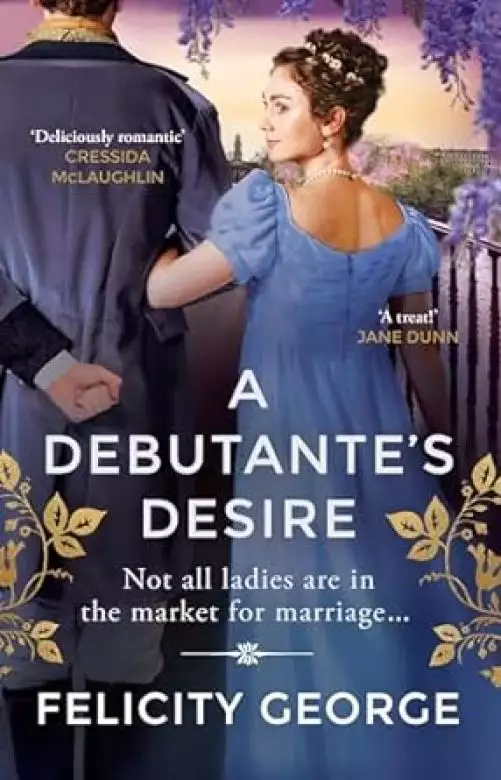

*The next sexy, hilarious and unputdownable book in The Gentleman of London series*

Release date: April 16, 2024

Publisher: Orion

Print pages: 336

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

Close

A Debutante's Desire

Felicity George

Oakwood Hall emerged from the snowy Yorkshire countryside, grey stone blending with grey sky. As John Tyrold cantered out of the ancient oak grove fronting the manor house, the mist creeping over the moors seemed to seep into his bones. Ever since his parents’ letter had arrived in London with news of Helen’s death, he’d anticipated a gloomy return to his childhood home; evidently even the weather wished to ensure his expectations were fulfilled.

A legion of familiar figures fanned out from the house to stand at attention, as if even the scullery maids had been summoned to greet John’s arrival. Which was a damned nuisance, of course. He’d hoped to slip in undetected to see his grieving parents, at least initially. Every servant knew the reason he had not returned home in eight years, and their minds no doubt dwelt upon that now. In general, John was indifferent to the opinions of others, but, oddly, here at Oakwood, he wasn’t.

The servants arranged themselves like statues, their breath clouding around their noses, their black clothes stark against the grim, grey vista. Everyone wore mourning for Helen, and, as his horse drew closer, John grew conscious of his brown hat and green greatcoat, realising for the first time that he ought to have acquired black attire before leaving town. It had been an oversight on his part, for he rarely thought of his clothes, but perhaps it would look like disrespect.

He tightened his numb fingers around the reins and halted Thunder in front of the formidable company. As he dismounted, his parents stepped forwards, his father tall with long white hair and his mother weeping, her arms outstretched.

‘My boy is home at last,’ Mrs Tyrold cried, enveloping John in a warm embrace. ‘But you’re not a boy any more, are you?’ Tears pooled along her lower lashes as she stroked his unshaven cheek. John was seventeen when last he’d seen her; he was five-and-twenty now. ‘All the same, how good it is to see my son. If only Helen were alive and well, then I could be happy again.’

John held her close. ‘There, there, Mother. All will be well,’ he said with as much conviction as he could muster. ‘I can’t stay long, but while I’m here I shall help in any way needed.’ Even a short absence from London was a strain because of the incessant demands of his ever-expanding fortune, but John loved his parents too well not to have cast aside business to return home when he’d received their heartbroken letter.

He glanced at his father, who looked careworn, his face lined, his eyes weary. ‘When is the funeral?’ John queried, his voice flat.

‘Tomorrow. We shall bury her in the Tyrold vault.’

‘Naturally,’ John responded curtly.

The wrinkles on his father’s forehead deepened. ‘Son, Helen was like a daughter to your mother and me.’

Mrs Tyrold buried her face into John’s chest, her sobs muffled against his greatcoat.

‘I know, Father,’ John said, more kindly. He rubbed his mother’s back. Dammit, now there was a lump in his throat, but John wouldn’t reveal any weakness here, in front of the entire household staff. ‘Come, Mother, let’s go inside. It’s far too cold to stand about, especially when there has so recently been illness in the house.’

Mrs Tyrold sniffled and broke the embrace to thread her arm through John’s.

A groom stepped forwards to lead Thunder to the stables, and John patted his horse’s neck before relinquishing the reins. ‘Take care of him, please,’ he said. ‘He’s been on the road for three days.’

‘Shall we expect your luggage by carriage later, sir?’ the groom asked.

‘No, no carriage follows,’ John replied. He’d packed his few changes of clothes in the saddlebags.

‘But, John, you will need a carriage to return to London,’ his mother said. She hung heavily on John’s arm, and her tread was slow as their feet crunched the icy gravel on their walk to the front door.

‘Thunder does very well,’ John reassured her.

The fashionable world scratched its head that he kept neither carriage nor any other trappings of a gentleman despite his nearly unparalleled wealth, but it suited John to have everyone believe him a miser. In truth, he did despise the unnecessary waste of money, and his horse did the job as well as a carriage, with much less expense.

His mother tightened her hold on his elbow. ‘I’m certain Thunder is a good horse, but the child cannot make such a long journey on horseback.’

John frowned as they stepped over the threshold and into the vaulted medieval hall, as oppressively cold and grey as the outside despite the crackle of logs in the vast stone hearth. ‘Whatever do you mean, Mother?’

It was his father who replied. ‘Flora will return with you, my son.’

John drew back, astonished his father would make such a request about Helen’s young daughter, but his reply withered on his lips as he noted movement by the hearth. Emerging from a makeshift construction of blankets and pillows was a slip of a mite wearing a black frock and clutching a large leather book to her chest.

The child’s appearance froze John, for the mass of burnished copper curls, the rosebud lips and the small nose were the spit of her mother – yet the owl-like eyes that returned his gaze with frank regard weren’t blue like Helen’s, but the unadulterated green of an oak leaf.

‘John, this is Flora,’ his mother said, her voice sounding muffled in John’s ears.

The servants filed in behind his parents. Aware that dozens of eyes watched, John disguised how the child’s appearance affected him. ‘Good day, Flora,’ he said, his bootsteps echoing as he approached the hearth. He knelt, facing her on her level. ‘I’m John.’

‘Yes, I know,’ she whispered, before pressing her lips together, as if sealing her mouth.

A dull ache throbbed in John’s chest. Helen had been an effervescent child, a ray of sunshine, but Flora was sombre beyond her years.

He tried again. ‘I’m pleased to make your acquaintance at last, although I’m terribly sorry it’s under such dreadful circumstances.’

She blinked, studying him.

Then her large eyes gleamed, abruptly animated. ‘What’s your favourite bird, John?’

John hid his surprise at her transformation. Birds were clearly a topic that interested her, and he knew from his own childhood experiences that she expected a proper answer. In such cases, nothing was worse than an adult who laughed, so he replied solemnly with the first bird that came to mind. ‘Owls.’

‘Tawny, barn, long-eared, or short-eared?’ she queried, her green gaze intense.

‘All owls,’ John replied and, suspecting she’d want him to justify his answer, he fabricated reasons, although it was the child’s appearance that had inspired his response. ‘I admire their solitary nature, their keen observational skills and the effectiveness of their hunt.’

Flora nodded approvingly. ‘If you wish to observe one in nature, look for their pellets. An owl’s nest will be nearby. Tomorrow, let’s search together. If we find a pellet, we can dissect it, for inside will be the tiny bones of mice and shrews, and we can reconstruct their skeletons.’

With that pronouncement, she marched out of the hall, still clutching her book. For a moment, John stared after her, marvelling at her obvious intelligence, but then the deep ache stirred again within his chest. The child had witnessed her mother’s slow death; what dreadful thoughts would invade her young mind as she sorted mouse bones?

John stood and turned to his parents, who gazed after Flora with misty eyes. The servants had dispersed, allowing him to speak candidly. ‘I cannot take that little one to London. She’s better off here, scampering over the moors in search of owls.’

His father shook his weary head. ‘Regardless, she must go with you. You’re her guardian now, per Helen’s will.’

‘Helen left you this.’ Mrs Tyrold extended a folded paper. ‘To explain, presumably.’

John took the letter and ripped the seal, his heart thudding at his name rendered in Helen’s familiar script. After all these years, what had she written?

As it turned out, very little, for only a few lines crossed the page.

My dearest John,

I leave you my precious doll and I trust that in your heart of hearts you know why. Flora has never known a papa’s love, although your own father did well by her. Love her, Johnny, for the sake of all which was once dear between us.

Helen

John’s hand shook, causing the written words to waver. Helen trusted his heart of hearts to know why? What the devil did she mean by that? Good God, if there had been a reason, why had he not received this letter years ago? Why hadn’t Helen …

Swiftly, John buried this disturbing new thought in the same deep hole where he concealed his old resentment, and refolded the paper. Her word choice likely meant nothing; Helen had been feverish for months before her death, according to his parents. ‘I shall act as the child’s guardian, but Helen writes nothing about London. It is best Flora remain in the only home she has ever known.’

‘I disagree, son.’ His father delivered his contradiction in a tone much firmer than John had ever heard from the quiet man. ‘This has been no life for her, especially during Helen’s long illness. Oakwood is too remote. You had Helen and Arthur to keep you company growing up, but Flora has always been alone. She needs other children—’

‘School, then,’ John said. ‘I shall find a school, for I am in no position to raise a child, nor would she be around other children in my company.’

‘But it’s time you settled down,’ his mother urged. ‘A proper home, a wife—’

‘I have no inclination towards fortune hunters, Mother. And women only want my money.’

‘Helen didn’t,’ his father ventured softly, looking at the floor.

John snorted. ‘You know how that turned out.’

Mrs Tyrold shot her husband a scowl before addressing John again. ‘Son, what happened with Helen is in the past. You have a full life ahead of you. Don’t you feel lonely?’

John shrugged. ‘I’m considering a dog.’

‘Be serious, John.’ His mother was evidently unamused for there was exasperation in her voice. ‘You must have a son to inherit this estate after you.’

‘Flora will inherit,’ John replied.

His father’s head snapped up from observing the flagstones. ‘You well know that Flora cannot inherit an estate entailed through the male line.’

‘As legal heir, I can change the entail. I shall be the first Tyrold heir ever to do so, but I assure you it can and will be done.’ John shoved Helen’s letter in his pocket. ‘And, as Flora’s guardian, I believe it is best if she remains here—’

‘No,’ Mrs Tyrold said with finality.

John lifted his brows, for it was the first time in his recollection in which either of his parents had told him no.

But his mother stood resolute. ‘Frankly, she is too much for us. We are not young, John – we were not young when we were blessed with you, our only child, but we grow old now.’

John felt the truth of her words. Lines that hadn’t been there eight years earlier were etched on her face, her red-gold hair was streaked with grey, and his father’s shoulders stooped with age. Mrs Tyrold’s slow and heavy tread John had attempted to dismiss as grief, but the truth was, his father had passed seventy and his mother was not much younger.

‘Flora is a handful, John,’ Mrs Tyrold said with a sigh. ‘Not without justification, mind you. She’s lived a difficult life in her few short years. Death, illness, more death, and now you suggest she continue to live with two aged people in this remote corner of Yorkshire? No, she needs youth and vitality. She needs firm but loving guidance. She needs you, and all you can provide her.’

John tossed aside his hat and ran his fingers through his long hair, his thoughts in turmoil. He couldn’t return to London with Flora in tow. If he wasn’t ready to face the explanation he’d have to offer his friends, he certainly wasn’t ready to parent a child who was the spitting image of the woman who’d broken his heart … except for those damnable green eyes.

And there was another concern. John had long ago made Flora the primary beneficiary in his will, and his arriving in London with a child people would suspect – quite rightly – of being the heiress to the Tyrold millions would cause a sensation. It was one thing for John to be hounded – he knew how to throw off fortune hunters – but a little girl? Flora would be a target of incessant toad-eating and flattery, if not worse. It was no way to grow up.

Yet John couldn’t disregard the only request his parents had ever made of him. It was simply a matter of managing the situation properly. Naturally, Flora must reside at a school. A sensible, homey institution where she’d receive a well-rounded education, perhaps with the daughters of prosperous shopkeepers.

That way, none amongst his circle of acquaintances need know of her existence until John decided they should.

John applied himself to locating such a place that very evening, writing a dozen inquiries by candlelight after Flora and his parents had gone to bed. Within a fortnight – despite spending every afternoon being pulled across the icy moors by a little red-haired wildling – he reached a satisfactory arrangement with a Miss Crayford at the David Street Girls’ Seminary in Mary Le Bone.

He described what he knew of the school as he left Oakwood Hall in a post-chaise a month later, Flora snuggled against his side. ‘It’s a small school, with about a dozen girls to be your friends. You will live there, but I shan’t be far away.’

‘I like to learn,’ Flora said. ‘And I think I shall enjoy having friends.’ Wrapped in blankets and furs, she swung her little legs on the bench seat, her gaze fixed on the icy moors outside the carriage window. In her lap rested the large leather volume she was rarely without, The Birds of Britain embossed on its cover. ‘Will you come and see me, John?’

‘On occasion, yes. I can visit, although I must be discreet when I do.’

She peered up at him, her owl-like eyes piercing. ‘Why?’

John tugged at his shirt collar, loosening its hold. ‘I’m rather well known.’

‘Mama said your fortune has made you famous. She showed me whenever your name appeared in the papers.’

John’s mind conjured a vision of Helen and Flora together, reading about him as if he were a fairy-tale character in a bedtime story, but he erased the imagining swiftly. It probably hadn’t been anything like that. Helen had perhaps mocked and ridiculed him, silently if not aloud. Had she hated him, even?

He despised these wonderings, which had come to him frequently in the last fortnight. He hadn’t wanted to resolve things when Helen was alive, so why did he care now?

Because now you have seen her child, a disturbing thought whispered.

Swiftly, John silenced it by returning to his conversation with Flora. ‘It’s not a nice thing to be famous.’

‘Why not?’ she asked in her solemn manner.

‘Because people constantly bother me. They fixate on me and pursue me relentlessly unless I am dismissive and rude. Even then, they attempt to force my attention in all manner of ways. I rarely go into company because I find it so …’ John hesitated, searching for the word which best described his sentiments. Exhausting wasn’t quite right. Nor was grating. It was something more complicated than that. Interacting with society confused him because he could never trust people’s motives. Except for his few close friends, when people were kind or attentive or acted as if they found him interesting, it was because they wanted something. ‘Because I find it difficult to discern who I can trust, Flora,’ he concluded at last. ‘If others learn of your connection to me, I’m afraid unkind people might treat you in confusing ways. I don’t want you to experience that until you’re ready.’

‘When will I be ready?’

John exhaled, considering. ‘You’re seven now?’ He knew the answer.

‘Eight in April.’

That gave John a decade, at least. Surely, within the next ten years, one of his friends would marry a lady John could trust to oversee an heiress’s coming out. ‘When you’ve completed school at eighteen, you will be ready.’

Flora studied him carefully. ‘And then I shall live with you?’

‘Perhaps.’ The girl’s eyes narrowed, as if she intended to question him further, but John changed the subject. ‘There’s one matter more to discuss, little one. I believe it’s best if you’re called Flora Jennings at school.’

Flora tilted her head. ‘But I’m Flora Tyrold.’

‘Yes, yes,’ John said quickly. ‘But that surname will connect you with me, whereas Jennings protects you from the unkind people I mentioned earlier.’

Flora’s lips turned down, but at last she nodded. ‘Very well. Jennings was Mama’s name, and I shall like that.’ Her green-eyed gaze fell to her book. ‘Do you have a pencil?’

‘A pencil? I believe so, yes.’ John reached into his coat pocket and shuffled round his pipe, his tobacco pouch and his coin purse until he felt the wooden cylinder. He extracted it, checked its tip – well sharpened enough for writing – and handed the instrument to Flora.

After opening her book, she wrote the name FLORA JENNINGS in careful block print with her left hand.

John’s breath hitched. The green eyes and now this? What did it mean that he and the child shared such a rare peculiarity? But scarcely had the question formulated before he scolded himself for thinking it. Surely it meant nothing other than his parents had imparted upon Helen their belief that it was cruel to tie back the hand of a left-handed child. If others were so sensible, left-handedness likely wouldn’t be so uncommon.

All the same, John’s chest ached with a profound sharpness, as if wounded anew. He drew Flora close and placed a kiss on her copper curls. She sighed, contented, closed her book, and soon fell asleep in his arms.

London

Georgiana Bailey strolled on the arm of her father’s wife, drawing courage from the beauty of the day. Hyde Park was a brilliant burst of opulence and colour during the late afternoon hour when the beau monde emerged, to see and be seen. On the fashionable bridle path Rotten Row, young bucks atop high-bred horses cantered past barouches and curricles, their occupants on display, while a sea of silk parasols, plumed bonnets, and tall-crowned hats navigated the tree-lined walkways. To Georgiana’s right, the Serpentine sparkled blue, dotted with swans and toy sailboats, and the laughter of the boys and girls playing along its edge lent a festive air.

The sight of the children warmed Georgiana’s heart. She promised herself for the thousandth time that somehow, one day, she’d purchase a garden for the residents of Monica House, the refuge she ran for women and children in distress. The garden would be a place for children to run and play amongst trees and flowers, and for the women, a sanctuary of beauty and peace, offering healing and hope to those who had suffered.

Today was the renaissance of all her dreams after months of despair; it was also her unofficial debut into the world of the haut ton, which was why she felt alert and tense, like a deer facing a pack of wolves. Georgiana knew that she appeared to fit the part in an indigo-blue redingote adorned with gold braid, but all the trimmings on earth wouldn’t long disguise the fact that she was the natural daughter of an opera singer, whose father had hidden her like a shameful secret, until now.

Regardless, for the sake of everything she held dear, Georgiana simply must make the ton accept her. The odds were stacked against her, as always. Society never looked kindly on illegitimacy, and the discovery that the moralist Duke of Amesbury had a bastard had already caused a stir. Never mind that Georgiana’s conception predated her father’s marriage by a few months; Amesbury’s hypocrisy was raising eyebrows and setting tongues wagging. The smallest misstep on Georgiana’s part would destroy her chance of acceptance, for the ton would judge her far more harshly than other young women. Like the deer amongst the wolves, the slightest falter could be her demise.

Yet failure wasn’t an option. The wellbeing of too many people depended upon her success.

‘These first few appearances will be the most challenging for both of us, Georgiana,’ said her father’s wife. Fanny Bailey, the Duchess of Amesbury, was an exceedingly pretty blonde lady in her mid-forties, a leader of high society for more than two decades and yet, now, on this all-important afternoon, there was a quiver in her rather girlish voice. She offered a smile as she smoothed the walnut-brown curls peeping from Georgiana’s bonnet brim, but the action was one of nervous energy rather than necessity. Georgiana had dressed herself, and she knew not a pin was out of place nor a hair astray. ‘You look lovely,’ the duchess continued, ‘and despite your protestations, I do want you to attempt to secure an advantageous match this Season. Have fun, dearest. Flirt – demurely, of course. As pretty and clever as you are, you’ll have a husband in no time, for everyone is thinking of marriage since Princess Charlotte’s engagement last month.’

Georgiana blinked, incredulous that the duchess was rehashing this dispute. For years, she’d remained steadfast against her father and his wife’s arguments for her marriage. The only reason she’d finally agreed to enter society this Season was because Monica House had recently lost a valuable benefactress, depriving the charity of much of its income.

All Georgiana’s thoughts were bent upon helping Monica House. She must raise a substantial sum of money for the charity to operate without a deficit, not to mention find funds to pay an arrear of debts and to restore her dream of establishing a school and the garden. Her successful debut into a social world filled with wealthy potential sponsors wasn’t coming a moment too soon.

‘No more talk of marriage, ma’am,’ Georgiana said firmly. ‘As I have said many times before, I am entering society to find sponsors for Monica House, not to find a husband.’ She squared her shoulders and lifted her chin as she surveyed the crowds before her, like a soldier facing the battlefield. ‘So with that in mind, please introduce me to the most charitable souls of your acquaintance.’

A tightness formed at the corners of Fanny’s lips. ‘First, make an effort with some eligible gentlemen, Georgiana. You underestimate the benefits of marriage to a man of breeding and fortune, both for yourself and your charity work. In fact, ready yourself now, dearest. Sir Ambrose Pratley-Finch comes your way. He has ten thousand a year, and he’s looking for a wife.’

An old man with wispy white hair weaved towards them, a leer on his florid face and a black armband tied round the sleeve of his mauve tailcoat.

Georgiana’s eyes widened. ‘You cannot be serious, ma’am! Pray, let us walk in the other direction before he approaches.’ She turned – intending to escape whether or not the duchess joined her – but Fanny clasped her hand, restraining her, and then it was too late to leave without appearing impertinent, a misstep Georgiana couldn’t afford.

‘Good afternoon, Sir Ambrose,’ Fanny said, responding to the baronet’s bow. ‘I’m pleased to see you looking well. Naturally, the duke and I were devastated to learn of the death of Lady Pratley-Finch in the autumn.’

The baronet, whose watery eyes scaled the length of Georgiana’s frock before peering at her face, dabbed his bulbous nose with a purple handkerchief. ‘Yes, yes. But life goes on. May I beg an introduction to your protégé, Duchess?’

With effort, Georgiana set her face into a pleasing expression while the introductions were made. After all, Sir Ambrose was a rich man and therefore it was worth her time to encourage him to donate to Monica House.

Her composure almost faltered when the baronet planted a raspy kiss on her gloved hand.

‘Stroll with me, my dear,’ Sir Ambrose said, speaking in a deep voice he must imagine was alluring. He tucked her hand into the crook of his elbow and manoeuvred her away from Fanny. ‘I don’t mind admitting I’m already quite in your thrall. I didn’t know Amesbury had a daughter until last week when Lady Frampton told me. Everyone’s talking of it, many not so kindly, but it doesn’t matter to me if you were born on the wrong side of the sheets. A duke’s daughter is a duke’s daughter, and I expect your papa intends to do well by you, eh?’

Still hoping for a donation, Georgiana formed her lips into what she hoped resembled a genuine smile. ‘My father is extremely good to me, sir,’ she said sweetly. The truth was, the fortune her father had bestowed upon her four years earlier was long spent on renovations to Monica House and other charitable deeds, but neither the duke nor the duchess knew that. ‘I am so truly blessed that I try to give a little back by running a charity house for women and children. Perhaps you might like to sponsor—’

The baronet pressed close, his sour breath on Georgiana’s cheek. ‘A bit of do-gooding is well enough for a lady, but a gentleman has bigger concerns, doesn’t he? I hear your mother was Anna Marinetti, La Grande Bellezza. Saw her perform countless times. By God, what a voice. What a figure, what a face. There never was anything more exquisite. You resemble her, you know. Haven’t got her shape, more’s the pity, but you’re still a handsome thing. Besides, you might yet put some meat on your bones. And you’re more of an age for me than most debutantes, eh?’

At six-and-twenty, Georgiana was old for a debutante, but that didn’t mean she was ‘of an age’ for an ancient lecher like Sir Ambrose.

If the baronet didn’t wish to donate to Monica House, Georgiana was done with his company. ‘Excuse me, Sir Ambrose,’ she said as prettily as she could muster. ‘But I must beg to return to the duchess.’

Sir Ambrose’s expression darkened, his bushy brows drawing together. ‘Don’t be so dismissive, my girl. There won’t be many as tolerant of your birth and as willing to make you an honourable offer as I am.’

Georgiana repressed a retort, for she couldn’t afford to give offence. ‘I do not intend to be dismissive, sir. I merely wish to be at the duchess’s side, as is right and proper for a debutante.’ Without giving him a chance to protest more, she curtsied and then darted to Fanny, who stood blinking innocently under a tree some distance away. ‘That was a cruel trick, ma’am,’ she hissed against the duchess’s plumed hat.

Fanny drew her lips into a circle. ‘You didn’t like Sir Ambrose?’ As Georgiana glared her response, the duchess shook her head, as if in disbelief. ‘I can’t think why, dearest. He’s rich and likely to die soon.’

Georgiana couldn’t help but smile. ‘Ah, now I know you’re only teasing.’

Fanny’s blue eyes twinkled. ‘About dreadful Sir Ambrose, yes. But I am quite serious about your finding a husband, so show me who you do like.’ With that pronouncement, the duchess swept her closed parasol towards Rotten Row, as if it were a fairy wand able to grant Georgiana her pick of husbands.

Exasperated, Georgiana followed the arc of the parasol over the promenading crowds as she readied her argument against marriage, for the thousandth time. ‘Ma’am, my work at Monica House consumes me …’

The rest of her words withered away as her attention was captured by a man approaching from the west with determined strides, his hands shoved deep into his pockets, a pipe dangling from his lips and a lanky black wolfhound at his side.

Georgiana drew herself up, raising on her tiptoes as she studied him, for he was none other than John Tyrold, one of the wealthiest men in Britain, and at the very top of Georgiana’s list of people to approach about Monica House. An introduction to Tyrold could change everything if she played her cards well; he was rich enough to reverse Monica House’s troubles by tossing out his pocket change. It was unimaginably good fortune to spot him on her first day out with Fanny, especially since he was famously a recluse.

‘Him?’ Fanny asked, having evidently followed Georgiana’s gaze. ‘Good Lord, child! Do you know who that is?’

Georgiana dropped down from her tiptoes, grinning. ‘I live at a charity house, not under a rock! All of London knows the legendary “King Midas” Tyrold on sight.’

It was said that everything Tyrold invested in multiplied its value manyfold, so that the man was hounded by every venturer and capitalist in the kingdom. It was also said that Tyrold was eccentric, brusque and unapproachable. That despite possessing the wealth of a king, he’d skin a flint if he could.

He certainly seemed to wear the evidence of his parsimony with apparent pride; as always, the same shabby brown hat shaded his stubble-darkened face, his olive-green frock coat was years out of fashion, and he must be the only gentleman under seventy in London who still sported long hair tied back into a queue, as if he were too cheap to visit a barber. Even his pipe was terribly outmoded, for the fashionable set had long preferred snuff.

‘Georgiana, you won’t succeed,’ Fanny cautioned. ‘Everyone has tried to catch Tyrold for years; he’s considered the prize of

A legion of familiar figures fanned out from the house to stand at attention, as if even the scullery maids had been summoned to greet John’s arrival. Which was a damned nuisance, of course. He’d hoped to slip in undetected to see his grieving parents, at least initially. Every servant knew the reason he had not returned home in eight years, and their minds no doubt dwelt upon that now. In general, John was indifferent to the opinions of others, but, oddly, here at Oakwood, he wasn’t.

The servants arranged themselves like statues, their breath clouding around their noses, their black clothes stark against the grim, grey vista. Everyone wore mourning for Helen, and, as his horse drew closer, John grew conscious of his brown hat and green greatcoat, realising for the first time that he ought to have acquired black attire before leaving town. It had been an oversight on his part, for he rarely thought of his clothes, but perhaps it would look like disrespect.

He tightened his numb fingers around the reins and halted Thunder in front of the formidable company. As he dismounted, his parents stepped forwards, his father tall with long white hair and his mother weeping, her arms outstretched.

‘My boy is home at last,’ Mrs Tyrold cried, enveloping John in a warm embrace. ‘But you’re not a boy any more, are you?’ Tears pooled along her lower lashes as she stroked his unshaven cheek. John was seventeen when last he’d seen her; he was five-and-twenty now. ‘All the same, how good it is to see my son. If only Helen were alive and well, then I could be happy again.’

John held her close. ‘There, there, Mother. All will be well,’ he said with as much conviction as he could muster. ‘I can’t stay long, but while I’m here I shall help in any way needed.’ Even a short absence from London was a strain because of the incessant demands of his ever-expanding fortune, but John loved his parents too well not to have cast aside business to return home when he’d received their heartbroken letter.

He glanced at his father, who looked careworn, his face lined, his eyes weary. ‘When is the funeral?’ John queried, his voice flat.

‘Tomorrow. We shall bury her in the Tyrold vault.’

‘Naturally,’ John responded curtly.

The wrinkles on his father’s forehead deepened. ‘Son, Helen was like a daughter to your mother and me.’

Mrs Tyrold buried her face into John’s chest, her sobs muffled against his greatcoat.

‘I know, Father,’ John said, more kindly. He rubbed his mother’s back. Dammit, now there was a lump in his throat, but John wouldn’t reveal any weakness here, in front of the entire household staff. ‘Come, Mother, let’s go inside. It’s far too cold to stand about, especially when there has so recently been illness in the house.’

Mrs Tyrold sniffled and broke the embrace to thread her arm through John’s.

A groom stepped forwards to lead Thunder to the stables, and John patted his horse’s neck before relinquishing the reins. ‘Take care of him, please,’ he said. ‘He’s been on the road for three days.’

‘Shall we expect your luggage by carriage later, sir?’ the groom asked.

‘No, no carriage follows,’ John replied. He’d packed his few changes of clothes in the saddlebags.

‘But, John, you will need a carriage to return to London,’ his mother said. She hung heavily on John’s arm, and her tread was slow as their feet crunched the icy gravel on their walk to the front door.

‘Thunder does very well,’ John reassured her.

The fashionable world scratched its head that he kept neither carriage nor any other trappings of a gentleman despite his nearly unparalleled wealth, but it suited John to have everyone believe him a miser. In truth, he did despise the unnecessary waste of money, and his horse did the job as well as a carriage, with much less expense.

His mother tightened her hold on his elbow. ‘I’m certain Thunder is a good horse, but the child cannot make such a long journey on horseback.’

John frowned as they stepped over the threshold and into the vaulted medieval hall, as oppressively cold and grey as the outside despite the crackle of logs in the vast stone hearth. ‘Whatever do you mean, Mother?’

It was his father who replied. ‘Flora will return with you, my son.’

John drew back, astonished his father would make such a request about Helen’s young daughter, but his reply withered on his lips as he noted movement by the hearth. Emerging from a makeshift construction of blankets and pillows was a slip of a mite wearing a black frock and clutching a large leather book to her chest.

The child’s appearance froze John, for the mass of burnished copper curls, the rosebud lips and the small nose were the spit of her mother – yet the owl-like eyes that returned his gaze with frank regard weren’t blue like Helen’s, but the unadulterated green of an oak leaf.

‘John, this is Flora,’ his mother said, her voice sounding muffled in John’s ears.

The servants filed in behind his parents. Aware that dozens of eyes watched, John disguised how the child’s appearance affected him. ‘Good day, Flora,’ he said, his bootsteps echoing as he approached the hearth. He knelt, facing her on her level. ‘I’m John.’

‘Yes, I know,’ she whispered, before pressing her lips together, as if sealing her mouth.

A dull ache throbbed in John’s chest. Helen had been an effervescent child, a ray of sunshine, but Flora was sombre beyond her years.

He tried again. ‘I’m pleased to make your acquaintance at last, although I’m terribly sorry it’s under such dreadful circumstances.’

She blinked, studying him.

Then her large eyes gleamed, abruptly animated. ‘What’s your favourite bird, John?’

John hid his surprise at her transformation. Birds were clearly a topic that interested her, and he knew from his own childhood experiences that she expected a proper answer. In such cases, nothing was worse than an adult who laughed, so he replied solemnly with the first bird that came to mind. ‘Owls.’

‘Tawny, barn, long-eared, or short-eared?’ she queried, her green gaze intense.

‘All owls,’ John replied and, suspecting she’d want him to justify his answer, he fabricated reasons, although it was the child’s appearance that had inspired his response. ‘I admire their solitary nature, their keen observational skills and the effectiveness of their hunt.’

Flora nodded approvingly. ‘If you wish to observe one in nature, look for their pellets. An owl’s nest will be nearby. Tomorrow, let’s search together. If we find a pellet, we can dissect it, for inside will be the tiny bones of mice and shrews, and we can reconstruct their skeletons.’

With that pronouncement, she marched out of the hall, still clutching her book. For a moment, John stared after her, marvelling at her obvious intelligence, but then the deep ache stirred again within his chest. The child had witnessed her mother’s slow death; what dreadful thoughts would invade her young mind as she sorted mouse bones?

John stood and turned to his parents, who gazed after Flora with misty eyes. The servants had dispersed, allowing him to speak candidly. ‘I cannot take that little one to London. She’s better off here, scampering over the moors in search of owls.’

His father shook his weary head. ‘Regardless, she must go with you. You’re her guardian now, per Helen’s will.’

‘Helen left you this.’ Mrs Tyrold extended a folded paper. ‘To explain, presumably.’

John took the letter and ripped the seal, his heart thudding at his name rendered in Helen’s familiar script. After all these years, what had she written?

As it turned out, very little, for only a few lines crossed the page.

My dearest John,

I leave you my precious doll and I trust that in your heart of hearts you know why. Flora has never known a papa’s love, although your own father did well by her. Love her, Johnny, for the sake of all which was once dear between us.

Helen

John’s hand shook, causing the written words to waver. Helen trusted his heart of hearts to know why? What the devil did she mean by that? Good God, if there had been a reason, why had he not received this letter years ago? Why hadn’t Helen …

Swiftly, John buried this disturbing new thought in the same deep hole where he concealed his old resentment, and refolded the paper. Her word choice likely meant nothing; Helen had been feverish for months before her death, according to his parents. ‘I shall act as the child’s guardian, but Helen writes nothing about London. It is best Flora remain in the only home she has ever known.’

‘I disagree, son.’ His father delivered his contradiction in a tone much firmer than John had ever heard from the quiet man. ‘This has been no life for her, especially during Helen’s long illness. Oakwood is too remote. You had Helen and Arthur to keep you company growing up, but Flora has always been alone. She needs other children—’

‘School, then,’ John said. ‘I shall find a school, for I am in no position to raise a child, nor would she be around other children in my company.’

‘But it’s time you settled down,’ his mother urged. ‘A proper home, a wife—’

‘I have no inclination towards fortune hunters, Mother. And women only want my money.’

‘Helen didn’t,’ his father ventured softly, looking at the floor.

John snorted. ‘You know how that turned out.’

Mrs Tyrold shot her husband a scowl before addressing John again. ‘Son, what happened with Helen is in the past. You have a full life ahead of you. Don’t you feel lonely?’

John shrugged. ‘I’m considering a dog.’

‘Be serious, John.’ His mother was evidently unamused for there was exasperation in her voice. ‘You must have a son to inherit this estate after you.’

‘Flora will inherit,’ John replied.

His father’s head snapped up from observing the flagstones. ‘You well know that Flora cannot inherit an estate entailed through the male line.’

‘As legal heir, I can change the entail. I shall be the first Tyrold heir ever to do so, but I assure you it can and will be done.’ John shoved Helen’s letter in his pocket. ‘And, as Flora’s guardian, I believe it is best if she remains here—’

‘No,’ Mrs Tyrold said with finality.

John lifted his brows, for it was the first time in his recollection in which either of his parents had told him no.

But his mother stood resolute. ‘Frankly, she is too much for us. We are not young, John – we were not young when we were blessed with you, our only child, but we grow old now.’

John felt the truth of her words. Lines that hadn’t been there eight years earlier were etched on her face, her red-gold hair was streaked with grey, and his father’s shoulders stooped with age. Mrs Tyrold’s slow and heavy tread John had attempted to dismiss as grief, but the truth was, his father had passed seventy and his mother was not much younger.

‘Flora is a handful, John,’ Mrs Tyrold said with a sigh. ‘Not without justification, mind you. She’s lived a difficult life in her few short years. Death, illness, more death, and now you suggest she continue to live with two aged people in this remote corner of Yorkshire? No, she needs youth and vitality. She needs firm but loving guidance. She needs you, and all you can provide her.’

John tossed aside his hat and ran his fingers through his long hair, his thoughts in turmoil. He couldn’t return to London with Flora in tow. If he wasn’t ready to face the explanation he’d have to offer his friends, he certainly wasn’t ready to parent a child who was the spitting image of the woman who’d broken his heart … except for those damnable green eyes.

And there was another concern. John had long ago made Flora the primary beneficiary in his will, and his arriving in London with a child people would suspect – quite rightly – of being the heiress to the Tyrold millions would cause a sensation. It was one thing for John to be hounded – he knew how to throw off fortune hunters – but a little girl? Flora would be a target of incessant toad-eating and flattery, if not worse. It was no way to grow up.

Yet John couldn’t disregard the only request his parents had ever made of him. It was simply a matter of managing the situation properly. Naturally, Flora must reside at a school. A sensible, homey institution where she’d receive a well-rounded education, perhaps with the daughters of prosperous shopkeepers.

That way, none amongst his circle of acquaintances need know of her existence until John decided they should.

John applied himself to locating such a place that very evening, writing a dozen inquiries by candlelight after Flora and his parents had gone to bed. Within a fortnight – despite spending every afternoon being pulled across the icy moors by a little red-haired wildling – he reached a satisfactory arrangement with a Miss Crayford at the David Street Girls’ Seminary in Mary Le Bone.

He described what he knew of the school as he left Oakwood Hall in a post-chaise a month later, Flora snuggled against his side. ‘It’s a small school, with about a dozen girls to be your friends. You will live there, but I shan’t be far away.’

‘I like to learn,’ Flora said. ‘And I think I shall enjoy having friends.’ Wrapped in blankets and furs, she swung her little legs on the bench seat, her gaze fixed on the icy moors outside the carriage window. In her lap rested the large leather volume she was rarely without, The Birds of Britain embossed on its cover. ‘Will you come and see me, John?’

‘On occasion, yes. I can visit, although I must be discreet when I do.’

She peered up at him, her owl-like eyes piercing. ‘Why?’

John tugged at his shirt collar, loosening its hold. ‘I’m rather well known.’

‘Mama said your fortune has made you famous. She showed me whenever your name appeared in the papers.’

John’s mind conjured a vision of Helen and Flora together, reading about him as if he were a fairy-tale character in a bedtime story, but he erased the imagining swiftly. It probably hadn’t been anything like that. Helen had perhaps mocked and ridiculed him, silently if not aloud. Had she hated him, even?

He despised these wonderings, which had come to him frequently in the last fortnight. He hadn’t wanted to resolve things when Helen was alive, so why did he care now?

Because now you have seen her child, a disturbing thought whispered.

Swiftly, John silenced it by returning to his conversation with Flora. ‘It’s not a nice thing to be famous.’

‘Why not?’ she asked in her solemn manner.

‘Because people constantly bother me. They fixate on me and pursue me relentlessly unless I am dismissive and rude. Even then, they attempt to force my attention in all manner of ways. I rarely go into company because I find it so …’ John hesitated, searching for the word which best described his sentiments. Exhausting wasn’t quite right. Nor was grating. It was something more complicated than that. Interacting with society confused him because he could never trust people’s motives. Except for his few close friends, when people were kind or attentive or acted as if they found him interesting, it was because they wanted something. ‘Because I find it difficult to discern who I can trust, Flora,’ he concluded at last. ‘If others learn of your connection to me, I’m afraid unkind people might treat you in confusing ways. I don’t want you to experience that until you’re ready.’

‘When will I be ready?’

John exhaled, considering. ‘You’re seven now?’ He knew the answer.

‘Eight in April.’

That gave John a decade, at least. Surely, within the next ten years, one of his friends would marry a lady John could trust to oversee an heiress’s coming out. ‘When you’ve completed school at eighteen, you will be ready.’

Flora studied him carefully. ‘And then I shall live with you?’

‘Perhaps.’ The girl’s eyes narrowed, as if she intended to question him further, but John changed the subject. ‘There’s one matter more to discuss, little one. I believe it’s best if you’re called Flora Jennings at school.’

Flora tilted her head. ‘But I’m Flora Tyrold.’

‘Yes, yes,’ John said quickly. ‘But that surname will connect you with me, whereas Jennings protects you from the unkind people I mentioned earlier.’

Flora’s lips turned down, but at last she nodded. ‘Very well. Jennings was Mama’s name, and I shall like that.’ Her green-eyed gaze fell to her book. ‘Do you have a pencil?’

‘A pencil? I believe so, yes.’ John reached into his coat pocket and shuffled round his pipe, his tobacco pouch and his coin purse until he felt the wooden cylinder. He extracted it, checked its tip – well sharpened enough for writing – and handed the instrument to Flora.

After opening her book, she wrote the name FLORA JENNINGS in careful block print with her left hand.

John’s breath hitched. The green eyes and now this? What did it mean that he and the child shared such a rare peculiarity? But scarcely had the question formulated before he scolded himself for thinking it. Surely it meant nothing other than his parents had imparted upon Helen their belief that it was cruel to tie back the hand of a left-handed child. If others were so sensible, left-handedness likely wouldn’t be so uncommon.

All the same, John’s chest ached with a profound sharpness, as if wounded anew. He drew Flora close and placed a kiss on her copper curls. She sighed, contented, closed her book, and soon fell asleep in his arms.

London

Georgiana Bailey strolled on the arm of her father’s wife, drawing courage from the beauty of the day. Hyde Park was a brilliant burst of opulence and colour during the late afternoon hour when the beau monde emerged, to see and be seen. On the fashionable bridle path Rotten Row, young bucks atop high-bred horses cantered past barouches and curricles, their occupants on display, while a sea of silk parasols, plumed bonnets, and tall-crowned hats navigated the tree-lined walkways. To Georgiana’s right, the Serpentine sparkled blue, dotted with swans and toy sailboats, and the laughter of the boys and girls playing along its edge lent a festive air.

The sight of the children warmed Georgiana’s heart. She promised herself for the thousandth time that somehow, one day, she’d purchase a garden for the residents of Monica House, the refuge she ran for women and children in distress. The garden would be a place for children to run and play amongst trees and flowers, and for the women, a sanctuary of beauty and peace, offering healing and hope to those who had suffered.

Today was the renaissance of all her dreams after months of despair; it was also her unofficial debut into the world of the haut ton, which was why she felt alert and tense, like a deer facing a pack of wolves. Georgiana knew that she appeared to fit the part in an indigo-blue redingote adorned with gold braid, but all the trimmings on earth wouldn’t long disguise the fact that she was the natural daughter of an opera singer, whose father had hidden her like a shameful secret, until now.

Regardless, for the sake of everything she held dear, Georgiana simply must make the ton accept her. The odds were stacked against her, as always. Society never looked kindly on illegitimacy, and the discovery that the moralist Duke of Amesbury had a bastard had already caused a stir. Never mind that Georgiana’s conception predated her father’s marriage by a few months; Amesbury’s hypocrisy was raising eyebrows and setting tongues wagging. The smallest misstep on Georgiana’s part would destroy her chance of acceptance, for the ton would judge her far more harshly than other young women. Like the deer amongst the wolves, the slightest falter could be her demise.

Yet failure wasn’t an option. The wellbeing of too many people depended upon her success.

‘These first few appearances will be the most challenging for both of us, Georgiana,’ said her father’s wife. Fanny Bailey, the Duchess of Amesbury, was an exceedingly pretty blonde lady in her mid-forties, a leader of high society for more than two decades and yet, now, on this all-important afternoon, there was a quiver in her rather girlish voice. She offered a smile as she smoothed the walnut-brown curls peeping from Georgiana’s bonnet brim, but the action was one of nervous energy rather than necessity. Georgiana had dressed herself, and she knew not a pin was out of place nor a hair astray. ‘You look lovely,’ the duchess continued, ‘and despite your protestations, I do want you to attempt to secure an advantageous match this Season. Have fun, dearest. Flirt – demurely, of course. As pretty and clever as you are, you’ll have a husband in no time, for everyone is thinking of marriage since Princess Charlotte’s engagement last month.’

Georgiana blinked, incredulous that the duchess was rehashing this dispute. For years, she’d remained steadfast against her father and his wife’s arguments for her marriage. The only reason she’d finally agreed to enter society this Season was because Monica House had recently lost a valuable benefactress, depriving the charity of much of its income.

All Georgiana’s thoughts were bent upon helping Monica House. She must raise a substantial sum of money for the charity to operate without a deficit, not to mention find funds to pay an arrear of debts and to restore her dream of establishing a school and the garden. Her successful debut into a social world filled with wealthy potential sponsors wasn’t coming a moment too soon.

‘No more talk of marriage, ma’am,’ Georgiana said firmly. ‘As I have said many times before, I am entering society to find sponsors for Monica House, not to find a husband.’ She squared her shoulders and lifted her chin as she surveyed the crowds before her, like a soldier facing the battlefield. ‘So with that in mind, please introduce me to the most charitable souls of your acquaintance.’

A tightness formed at the corners of Fanny’s lips. ‘First, make an effort with some eligible gentlemen, Georgiana. You underestimate the benefits of marriage to a man of breeding and fortune, both for yourself and your charity work. In fact, ready yourself now, dearest. Sir Ambrose Pratley-Finch comes your way. He has ten thousand a year, and he’s looking for a wife.’

An old man with wispy white hair weaved towards them, a leer on his florid face and a black armband tied round the sleeve of his mauve tailcoat.

Georgiana’s eyes widened. ‘You cannot be serious, ma’am! Pray, let us walk in the other direction before he approaches.’ She turned – intending to escape whether or not the duchess joined her – but Fanny clasped her hand, restraining her, and then it was too late to leave without appearing impertinent, a misstep Georgiana couldn’t afford.

‘Good afternoon, Sir Ambrose,’ Fanny said, responding to the baronet’s bow. ‘I’m pleased to see you looking well. Naturally, the duke and I were devastated to learn of the death of Lady Pratley-Finch in the autumn.’

The baronet, whose watery eyes scaled the length of Georgiana’s frock before peering at her face, dabbed his bulbous nose with a purple handkerchief. ‘Yes, yes. But life goes on. May I beg an introduction to your protégé, Duchess?’

With effort, Georgiana set her face into a pleasing expression while the introductions were made. After all, Sir Ambrose was a rich man and therefore it was worth her time to encourage him to donate to Monica House.

Her composure almost faltered when the baronet planted a raspy kiss on her gloved hand.

‘Stroll with me, my dear,’ Sir Ambrose said, speaking in a deep voice he must imagine was alluring. He tucked her hand into the crook of his elbow and manoeuvred her away from Fanny. ‘I don’t mind admitting I’m already quite in your thrall. I didn’t know Amesbury had a daughter until last week when Lady Frampton told me. Everyone’s talking of it, many not so kindly, but it doesn’t matter to me if you were born on the wrong side of the sheets. A duke’s daughter is a duke’s daughter, and I expect your papa intends to do well by you, eh?’

Still hoping for a donation, Georgiana formed her lips into what she hoped resembled a genuine smile. ‘My father is extremely good to me, sir,’ she said sweetly. The truth was, the fortune her father had bestowed upon her four years earlier was long spent on renovations to Monica House and other charitable deeds, but neither the duke nor the duchess knew that. ‘I am so truly blessed that I try to give a little back by running a charity house for women and children. Perhaps you might like to sponsor—’

The baronet pressed close, his sour breath on Georgiana’s cheek. ‘A bit of do-gooding is well enough for a lady, but a gentleman has bigger concerns, doesn’t he? I hear your mother was Anna Marinetti, La Grande Bellezza. Saw her perform countless times. By God, what a voice. What a figure, what a face. There never was anything more exquisite. You resemble her, you know. Haven’t got her shape, more’s the pity, but you’re still a handsome thing. Besides, you might yet put some meat on your bones. And you’re more of an age for me than most debutantes, eh?’

At six-and-twenty, Georgiana was old for a debutante, but that didn’t mean she was ‘of an age’ for an ancient lecher like Sir Ambrose.

If the baronet didn’t wish to donate to Monica House, Georgiana was done with his company. ‘Excuse me, Sir Ambrose,’ she said as prettily as she could muster. ‘But I must beg to return to the duchess.’

Sir Ambrose’s expression darkened, his bushy brows drawing together. ‘Don’t be so dismissive, my girl. There won’t be many as tolerant of your birth and as willing to make you an honourable offer as I am.’

Georgiana repressed a retort, for she couldn’t afford to give offence. ‘I do not intend to be dismissive, sir. I merely wish to be at the duchess’s side, as is right and proper for a debutante.’ Without giving him a chance to protest more, she curtsied and then darted to Fanny, who stood blinking innocently under a tree some distance away. ‘That was a cruel trick, ma’am,’ she hissed against the duchess’s plumed hat.

Fanny drew her lips into a circle. ‘You didn’t like Sir Ambrose?’ As Georgiana glared her response, the duchess shook her head, as if in disbelief. ‘I can’t think why, dearest. He’s rich and likely to die soon.’

Georgiana couldn’t help but smile. ‘Ah, now I know you’re only teasing.’

Fanny’s blue eyes twinkled. ‘About dreadful Sir Ambrose, yes. But I am quite serious about your finding a husband, so show me who you do like.’ With that pronouncement, the duchess swept her closed parasol towards Rotten Row, as if it were a fairy wand able to grant Georgiana her pick of husbands.

Exasperated, Georgiana followed the arc of the parasol over the promenading crowds as she readied her argument against marriage, for the thousandth time. ‘Ma’am, my work at Monica House consumes me …’

The rest of her words withered away as her attention was captured by a man approaching from the west with determined strides, his hands shoved deep into his pockets, a pipe dangling from his lips and a lanky black wolfhound at his side.

Georgiana drew herself up, raising on her tiptoes as she studied him, for he was none other than John Tyrold, one of the wealthiest men in Britain, and at the very top of Georgiana’s list of people to approach about Monica House. An introduction to Tyrold could change everything if she played her cards well; he was rich enough to reverse Monica House’s troubles by tossing out his pocket change. It was unimaginably good fortune to spot him on her first day out with Fanny, especially since he was famously a recluse.

‘Him?’ Fanny asked, having evidently followed Georgiana’s gaze. ‘Good Lord, child! Do you know who that is?’

Georgiana dropped down from her tiptoes, grinning. ‘I live at a charity house, not under a rock! All of London knows the legendary “King Midas” Tyrold on sight.’

It was said that everything Tyrold invested in multiplied its value manyfold, so that the man was hounded by every venturer and capitalist in the kingdom. It was also said that Tyrold was eccentric, brusque and unapproachable. That despite possessing the wealth of a king, he’d skin a flint if he could.

He certainly seemed to wear the evidence of his parsimony with apparent pride; as always, the same shabby brown hat shaded his stubble-darkened face, his olive-green frock coat was years out of fashion, and he must be the only gentleman under seventy in London who still sported long hair tied back into a queue, as if he were too cheap to visit a barber. Even his pipe was terribly outmoded, for the fashionable set had long preferred snuff.

‘Georgiana, you won’t succeed,’ Fanny cautioned. ‘Everyone has tried to catch Tyrold for years; he’s considered the prize of

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...

A Debutante's Desire

Felicity George

Copyright © 2026 All Rights Reserved