- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

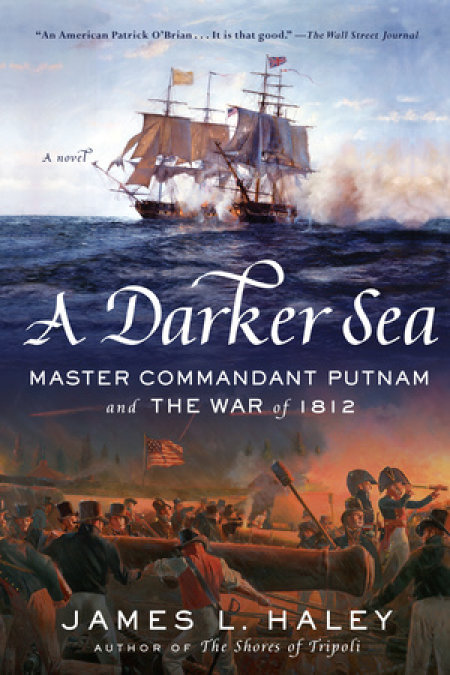

The second installment of the gripping naval saga by award-winning historian James L. Haley, featuring Commander Bliven Putnam, chronicling the build up to the biggest military conflict between the United States and Britain after the Revolution—the War of 1812.

At the opening of the War of 1812, the British control the most powerful navy on earth, and Americans are again victims of piracy. Bliven Putnam, late of the Battle of Tripoli, is dispatched to Charleston to outfit and take command of a new 20-gun brig, the USS Tempest. Later, aboard the Constitution, he sails into the furious early fighting of the war.

Prowling the South Atlantic in the Tempest, Bliven takes prizes and disrupts British merchant shipping, until he is overhauled, overmatched, and disastrously defeated by the frigate HMS Java. Its captain proves to be Lord Arthur Kington, whom Bliven had so disastrously met in Naples. On board he also finds his old friend Sam Bandy, one of the Java's pressed American seamen kidnapped into British service. Their whispered plans to foment a mutiny among the captives may see them hang, when the Constitution looms over the horizon for one of the most famous battles of the War of 1812 in a gripping, high-wire conclusion. With exquisite detail and guns-blazing action, A Darker Sea illuminates an unforgettable period in American history.

Release date: November 14, 2017

Publisher: G.P. Putnam's Sons

Print pages: 400

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

A Darker Sea

James L. Haley

Copyright © 2017 James L. Haley

Prologue: The Hound in Blue

In his cabin at the stern of the brig Althea, Sam Bandy dressed as he sipped the morning’s first cup of coffee, rich and full-bodied, from Martinique. Sped into Charleston on a fast French ship with a dry hold, it tasted of neither mold nor bilge water. He was lucky to have gotten it in, avoiding the picket of British cruisers who, in the never-ending mayhem of the Napoleonic wars, sought to sweep all French trade from the seas. It might well have ended in the private larder of an English frigate captain. Now he had brought a quarter-ton of it to Boston, tucked into his hold along with the cotton and rice that one expected to be exported from South Carolina.

Yes, the life of a merchant mariner suited him, and it endlessly amused him. If one wanted a bottle of rum in Charleston, the cane was grown in the West Indies, where it was rendered into sugar and its essential byproduct, molasses. Thence they were taken by ship and, passing almost within sight of Charleston, delivered all the way to Boston, or Newport. There the scores of Yankee distilleries manufactured the rum, which then had to be loaded and taken back south to Charleston, which was halfway back to the Caribbean. And money was made at each exchange.

Sam ascended the ladder topside, coffee in hand, snugging his hat upon his head—a blue felt Bremen flat cap that a German sailor had offered him in trade for his American Navy bicorn. Sam had surprised the German with how readily he accepted the exchange, for in truth he felt no sentimental attachment to it at all. There were several considerations that impelled him to separate from the Navy. The death of his father during the Barbary War and the disinterest of his brothers placed the responsibility for their Abbeville plantation on his shoulders. And the Navy’s penchant for furloughing junior officers for months at a time, and then recalling them without regard for the seasonal imperatives of planting or harvesting, he could not accommodate. Most important, on his voyage home from the Mediterranean on the Wasp, he had brought the daughter of the American former consul to Naples, and she had become his wife. Naturally he wished to provide her and their growing family the gracious life he had known, and shipping provided them a measure of comfort even beyond that of their neighbors.

And this would be a profitable trip. Their South Carolina cotton for the Yankee mills had brought him eighteen cents per pound and paid for the trip, leaving the rice, some indigo, and the Martinique coffee as pure profit. Topside, he observed his first officer, Simon Simpson, directing stevedores down into his hold. Simpson was astonishingly tall and brawny, dishfaced, with wild black hair; he knew his trade but was not overly bright, but then, apart from captains, what men who became merchant sailors were?

Their lack of schedule suited Sam; they had tied up halfway out the Long Wharf, selling until his hold was empty, and his taking on new cargo could not have passed more conveniently. As he reflected, Boston’s famous Paul Revere was in his mid-seventies, but still innovating, still trying his hand at new business. His late venture into foundry was a rousing success, and Simpson lined the bottom of Althea’s hold with cast-iron window weights, fireplace accoutrements—andirons, pokers—and stove backs. Nothing could have provided better ballast, and atop these he loaded barrels of salt fish, all securely tied down. This left room for fine desks and bookcases from the celebrated Mr. Gould. Upon Sam’s own speculation, apart from that of his co-owners of the ship, he visited Mr. Fisk’s shop and bought a quantity of his delicate fancy card tables and side chairs, for which he expected the ladies of Charleston to profit him most handsome. Fisk’s lyre-backed chairs were in the style of Hepplewhite of London, and when Sam visited Fisk and Son to make the purchase, it caught his ear that more than one patron expressed his pleasure that Fisk’s fine workmanship has soured the market for Hepplewhite itself, so disgruntled had people become with the British interference with their trade.

The Long Wharf, with its glimpse of Faneuil Hall at its head, the taverns he had frequented in their nights here, the dockside commotion, the frequent squeals of seagulls, the salt air beyond his West Indies coffee, all left him deeply happy, but he was ready to go home. “Mr. Simpson!” he called out.

Simpson left his station at the hatch and joined him by the wheel. “Good morning, Captain.”

“Good morning, Mr. Simpson. The tide begins to run in three hours. Can we be ready by then?”

“No question of it, we are almost finished.”

“Excellent. Now, if you please, divert two of those Fisk chairs to my cabin. There you will find on my desk a package, addressed to the Putnam family in Litchfield, Connecticut. Take it to the post office and dispatch it. The Port Authority is right close by there. Arrange a pilot for us, come back, check the stores, and prepare to get under way.”

Ah, the Putnams. Sam did not miss the Navy, but he missed Bliven Putnam. Their midshipman’s schooling together on the Enterprise, their learning the handling of sabres together, their fighting Barbary corsairs together, even their fumbling attempts to bridge the cultural gap between Connecticut and South Carolina, and their punishment together at the masthead of the President mandated by Commodore James Barron for their having fought each other all had bonded them in a way that would have been imperishable even had Barron not compelled them to swear their friendship to each other. Sam could not absent himself from the ship for a week, which would gain him only a day’s visit to Litchfield, but he could send Bliven a sack of this rich coffee.

By ten Simpson had returned, and Sam hoisted the flags, signaling his imminent departure. With crew counted and hatch secured, Sam cast off, moving ever so slowly under a single jib and topsail into the harbor. The wind was from the northwest, which could not have served them better.

At the end of the wharf the pilot boat appeared, a small, sleek, low-waisted schooner, which hoisted Althea’s name in signal flags. Sam answered and fell in behind her gratefully. In Boston’s shallow bay the tides ran swiftly; once, he visited the other side of the city when the tide fell just to see the sight of Back Bay emptying out as fast as a man could walk; such flats were no place to get trapped. But this pilot very clearly knew what he was doing; the schooner was under a full set, and Sam had to loose his courses to keep up. They passed through the channel between Long and Deer Islands, and could see Lovell Island off their starboard bow. At this point the pilot came about, wishing Althea fair sailing; Sam signaled his thanks and steered east-southeast for the northern curl of Cape Cod. If the wind held, they should round the cape and be halfway down that seemingly interminable spit of sand when dark fell. He would be safe on a southerly course and well clear of Nantucket by morning, when he could set a new course, if the wind permitted, west-southwest for Long Island.

If it were not for the knowledge of going home, Sam would not relish the southward voyage. South by west was the most direct course to Cape Hatteras, but that would place him in the very teeth of the irresistible, opposing push of the Gulf Current. More distant in miles but infinitely faster it was to steer closer inshore along the mid-Atlantic and follow the eddying cold-water currents that would aid him.

Their seventh day out, Sam awoke to the accustomed clatter of the cook setting the tray of his breakfast on his desk. He did not mind, for every morning it reminded him of the glorious luxury of not being in the Navy, that every morning there were eggs and bacon and toasted bread for breakfast. On this voyage he did rather feel obligated to share his Martinique coffee with the crew, but it was a small cost to see the men feeling favored, and thus working with a more congenial will.

He dressed and glanced at a chart on the table, estimating in rough how far they must have come during the night. Topside at the wheel he saw his tall, wire-haired first mate, keeping a firm grip on the wheel in a stout wind from their starboard quarter. “Good morning, Mr. Simpson.”

“Good morning, Captain.”

Sam regarded the wind and the set of sails. “Steer east-sou’east until noon, then make due south.”

“Very good, sir, east-sou’east she comes.” Simple Simpson eased the helm a few points to port.

There was no need to explain why. Their southerly course had brought them almost to the outer banks of North Carolina. Now it was necessary to stand out far enough to avoid those coastal shoals whose locations changed with every storm, shallows that had brought numberless crews to grief, yet not stand so far out as to meet the strongest opposition of the Gulf Current, which here compressed as it rounded the Hatteras Cape and was here at its swiftest. If they made that mistake they could labor all day with their sails bellied full out and end the day not five miles farther on than when they started. It was a delicate calculation, but they would know if they went too far, for old sailors had many times told Sam, and he had himself once discovered the truth of it, that the inner edge of the warm Gulf Current was so sharp and sudden that in crossing it, water brought up from the bow and the stern might be twenty degrees different in temperature.

At the same moment in the sea cabin of His Majesty’s sloop-of-war Hound, twenty-two guns, Captain Lord Arthur Kington in his dressing gown poured himself a glass of Madeira. Two weeks out of Halifax, bound for Bermuda, but empty-handed. They had not raised a single French sail to engage, nor even an American merchant to board and harvest some pressed men. For days now they had been plowing through the drifting mess of the Sargasso Sea, no doubt snagging strands of the olive-brown weeds that would hang on their barnacles and slow them down.

How in bloody hell could he have fallen from command of a seventy-four- to a twenty-two-gun sloop? For six years he had sailed in purgatory like the Flying Dutchman, each morning asking and answering the same question of himself, unable to break the cycle of it. It was difficult to comprehend how that incident in Naples had precipitated such a consequence. In attempting the apprehension of a deserter from a dockside tavern he and everyone else knew he was carrying out Crown policy. His fault, apparently, lay in attending a diplomatic reception while his press gang was assaulted and bested by a clot of drunken American sailors. No captain of a seventy-four would be seen in the company of his press gang; the notion was absurd, and he the son of a duke. What did they expect of him? Apparently, that his press gang prey only upon victims foreign or domestic, beyond the protective circle of their shipmates. It was his lieutenant on the Hector who had acted imprudently, but in the long-established calculus of the Royal Navy, he as captain should have foreseen such a circumstance and ordered his lieutenant to greater caution. That junior officer had not suffered for the act, he had later been raised from the Hector’s third officer to second, but it was Kington himself who, in response to the diplomatic stink that the Americans had fomented, had to be punished. And yet he wondered if there were not more to it, whether some key bureaucrat in the Admiralty had simply conceived a dislike for him.

At least the Admiralty had broken him in command only and not in rank, an admission that they needed his service as one who would willingly overhaul vessels on the high seas and take off what men were needed to crew His Majesty’s ships. The need was bottomless, for desertions were constant, and Napoleon simply would not be crushed. Kington’s conclusion was that his value to the Navy lay in impressing men in ways that could not be readily discovered, and in six years at this he had come to excel. The Navy needed him but would not acknowledge him; it was a circumstance that left him feeling ill used. Yet, if he did but do his duty, without complaint, and without overmuch using family influence on the Admiralty, he would work his way back up to his former station. This was certain, for even now a new frigate was waiting for him in Bermuda to take command once he brought in the Hound with a merchant prize or two, and some well-broken American sailors.

Thus he served, secure in the knowledge that the Royal Navy needed pressed men more than ever—and more particularly they needed him, for after that affair with the American frigate Chesapeake, their need for impressment was forced into still greater subterfuge. Infinitely more so than Naples, the Leopard–Chesapeake encounter had altered the dynamics of impressment. Doubtless, it had been less than prudent, or at least less than sporting, for Post Captain Humphreys of H.M.S. Leopard to pour broadsides into the unprepared American frigate in peacetime, but it was open and obvious that the Americans had been enlisting British deserters into their crews. The American captain, some fellow named Barron, had been court-martialed and suspended for not fighting his ship to the last, irrespective of the hopelessness of the contest.

Kington screwed up his mouth into a smile. That said much for the American frame of mind, but not their practicality. Barron had had no chance. His guns were unloaded, rolled in, their tompions in place. His decks were piled with stores in preparation for a long cruise; when approached by the Leopard, Barron, knowing they were not at war with Britain, had not beat to quarters. Had he resisted, his crew would have been slaughtered as they limbered up the guns. As it was, the American was lucky to lose only four killed and eighteen, including Barron himself, wounded. Humphreys had seized four men from the Chesapeake, and then, the worst insult of all, refused Barron’s surrender—they were not at war, after all—and left him there on his floating wreck. God help them if they ever encountered Barron again, he would sell his life very dearly indeed.

Of the four men Humphreys had seized, one was a Canadian, whom he hanged. They did have some color of justification for taking Canadians, to whom the Americans presumed to grant naturalized citizenship. How dare they? His Majesty’s government of course refused to recognize American naturalization. They were naval pretenders even as they were still pretenders as a nation, and no great attention need be paid them except for taking likely-looking seamen.

Now Kington knew that his exile was at an end; a new command awaited him in Bermuda, but he had concluded that he could not enter empty-handed, and he had turned to the northwest, crossing and riding the Gulf Current into the waters of the American coastal trade. Even as he was thinking they must sight a vessel on this day, he cocked his head at the faint cry above the deck overhead, of deck, sail ho. He straightened his dressing gown and seated himself at his desk, waiting for the rap at his door, which came only a moment later. “Enter,” he said quietly.

“Beg pardon, m’lord.” A lieutenant stood at attention and made his respects. “The lookout has sighted a ship bearing to the southwest.”

Kington affected not to look up from the papers on his desk. “What do you make of her?”

“An American merchantman, m’lord, a large brig, low in the water, heading south.”

“Very well. Make all sail to overtake her. I will come up.”

“Very good, m’lord.” The lieutenant made his respects again and departed.

Kington pulled a pair of brilliant white silk stockings up his calves, and then donned equally white knee breeches, which he fastened at the waist and knees. The talk was that the Royal Navy was going to change at any time to trousers for officers, as well as the enlisted men, who already wore them. He hated the notion. Trousers—inelegant, egalitarian, shapeless—suitable for the common sailors but certainly not for officers. After regarding his shiny white calves in the mirror, he buckled his sword about his waist and selected a coat from his wardrobe, the blue frock, undress but bearing the dual epaulettes that signified a captain of more than three years’ experience. It was hard to bear how many years, since Naples, but his circumstances would improve soon enough. He took up his glass and ascended the ladder to the quarterdeck.

The courses blocked his view down the deck, and he slung an arm through the mizzen’s starboard ratlines, leaned out and focused the American in his glass. Yes, it was a large brig, low and slow; they were gaining on him rapidly and he could not but have seen him. This should be a good day.

“What is your pleasure, m’lord? Shall you hail him?”

“Beat to quarters, Mr. Evans, ready your starboard bow chaser. At six hundred yards put a shot through his rigging. That will hail him well enough.”

“Beat to quarters!” Evans barked to the bosun, and an instant later the ship leapt to life in response to the drum’s tattoo. Both officers knew this was probably unnecessary when their quarry was an apparently unarmed merchant vessel, but both knew equally that an overawing display of firepower was the surest guarantor of a passive reception.

Aboard the Althea, Sam Bandy had been alerted to the approach of the British sloop and followed her through his glass, noting the deployment of starboard studding sails to increase her speed. He was studying her even as he saw the flash and smoke of her bow chaser; its booming report reached him almost simultaneously with the singing of a ball through his rigging. He started and shot his gaze upward at a loud pop, and beheld a rip in the main topsail, one edge flapping in the wind. He turned his head to the right, waiting for and then seeing the small splash a hundred yards out or more. Unarmed and laden too heavily to run, he had no choice but to furl his sails and wait for what fate should bring.

“She is bringing in her sails, m’lord,” said Evans. “It looks as if she means no resistance.”

“Good,” said Kington. “Have the bosun swing out the cutter. You and I will go over with ten Marines for escort.”

At the cutter’s approach, Sam had a rope boarding ladder lowered. Eight Marines came smartly up in coats of brilliant scarlet, flanking the ladder, then two officers in blue frocks, and two more Marines.

Bandy faced them, arms akimbo, several paces in front of his curious and apprehensive crew.

“I am Captain Lord Arthur Kington, of His Majesty’s sloop-of-war Hound. Are you the master of this vessel?”

“I am Samuel Bandy, captain of the brig Althea.” Sam squared his shoulders against him. “By what right do you stop an American ship in international waters?” he demanded.

“By the authority of Orders in Council of His Majesty’s government,” he said highly. “We are at war with France, and we are charged to stop ships, search for deserters, and seize ships which are carrying contraband bound for French ports. What is your cargo?”

“Your orders are of no effect upon American ships.”

“Mr. . . . Bandy, my broadside gives me all the authority I need. I ask you again, what is your cargo?”

“Salt fish, and kitchenware, and furniture.”

“Where bound?”

“We are seven days out of Boston, bound for Charleston.”

“I see. I require to see your manifest, and after that to inspect your hold. Take us down to your cabin.”

Sam clattered down the ladder to his small cabin, followed by the two officers and behind them two of the Marines. From a shelf he pulled the log book and extracted the three pages of manifest, detailing his cargo to the last item.

He handed the papers over to Kington, who rattled the sheets as he barely glanced at them before folding them back along their existing creases and tucking them into his coat pocket. “Well, I say, you are a lively-looking fellow,” said Kington.

Sam squinted and shook his head. “What?”

“We are searching for a Canadian deserter who bears the singularly appropriate name of Lively. Do you claim that the name means nothing to you?”

Sam was truculent. “Of course it means nothing to me. Why should it?”

“Because”—Kington looked Sam down and up and down again—“he stands about five feet nine inches, weight thirteen stone, very fair complected, reddish to blond hair.” He looked more closely. “Blue eyes. Did you really believe we would never discover you?”

“Damn your eyes, I am Samuel Bandy of South Carolina, captain and part owner of this vessel!”

Kington crossed his arms doubtfully. “Well, your accent is plausible. Still, that can be affected. Let me see your protection.”

“God damn it, I am the captain! I don’t carry proof of my citizenship!”

Kington tossed his head lightly. “Well, then.”

“Wait, I have my master’s license. Wait.” This was a document that he never expected that he would have to produce. He knew it was in a pouch of papers in his sea chest, and he dropped to his knees and flung open its lid.

“Hold!” barked Kington. The Marines who flanked him lowered their muskets at him. “Move very slowly.”

“Bastard,” muttered Sam. He rose again, unfolding his master’s license and handing it to Kington, who glanced about the cabin.

“The light in here is very poor.” He ambled over to the stern windows and opened one, sitting on its sill and leaning partly outside. “Now, let us see.” He mumbled the lines as he read them. “Oh, dear!” He opened his fingers and the paper fluttered down to the rolling sea.

Sam swelled up but checked himself as the Marines took a half-step forward en garde.

Kington tapped his index finger against his chin. “Perhaps you are who you say you are, but perhaps not. You answer the wanted man’s description too closely to dismiss the matter. Prudence dictates I shall bring you to Bermuda for more certain identification.”

“Wait a minute, I know you!” Sam shook his head. “From where do I know you?”

Kington looked at him with his haughty expectation.

Sam’s finger shot out at him. “Naples! After the war, the Barbary War, the American consulate, you had an altercation with Commodore Preble.”

“Indeed? I cannot say that I remember you at all. I do remember one particularly impudent lieutenant, but it was not you. Mr. Evans?”

“M’lord?”

“We will select a prize crew to take this vessel to Bermuda. Poll the American crewmen. Those who carry protections and wish to go home we will put ashore when we reach Bermuda and they can catch a ship home as best they can. Naturally, any who wish to volunteer into His Majesty’s service will be welcome to enlist.” The two officers chuckled. Once carried to Bermuda, it could take months for some neutral ship to carry them home again.

“You’re just a damned pirate,” spat Sam. He knew that Kington would have no trouble finding enlistments among his crew. In the American merchant service, as in the Navy, a fair portion of his sailors went to sea to escape their problems on land. Among the men were surely some whose fortunes had sunk so low—wanted by the law, or in the shadow of debtors’ prison—that a foreign ship seemed as viable an escape as walking into the Western wilderness, with the advantage that there were no bears or Indians. Given that they had no way home from Bermuda, it was tantamount to impressment just the same.

Kington smirked. “Damn fine chairs. Hepplewhite, by the make?”

“Fisk of Boston, damn you, and so stamped on the back of each.” He swept an arm out grandly. “But please, have them. They will show very fine in a pirate’s cabin.”

“That remark,” said Kington quietly, “will cost you six lashes, as the lightest of warnings. Provoke me further and you will regret it in proportion. Now, will you come quietly, or must we bind you? Before you answer, let me warn you that if you give me your parole to submit and then resist, I will surely hang you. I have no scruple about it.”

“No, I have no doubt of that.” He inclined his head toward a pine wardrobe. “Am I allowed to keep my clothes?”

“Certainly not. You will be fitted out in His Majesty’s uniform for an able seaman.” He glanced down. “You may keep your shoes, however. Shoes are in short supply.”

“What of my clothes?”

“We will keep them safe. If your story proves out, they will be returned to you.”

“Well, they are too large for you, at any rate. But perhaps your tailor can take them in for you.”

“Six more lashes, and I urge you, do not build up a large account.”

The swell on this morning was easy, as two Marines descended the boarding ladder to their cutter. Kington scanned about Althea’s deck and remembered that he had not inspected the hold. Ah, well. He had the manifest, and in this circumstance judged that sufficient. He had the ship; the nature of the cargo they could ascertain at leisure.

“Mr. Evans.”

“Yes, m’lord?”

“Inspect the crew for their protections. I will send the cutter back with a prize crew. Those who wish to enlist with us send back across with the boat. With luck, it will be an even exchange and we will both have a full complement. Then you will follow me to Bermuda.”

“Very good, m’lord.” He made his respects as Kington and the remaining Marines descended to the cutter.

As they approached the sloop, Sam saw that she had turned a bit in the current, and he could make out the name hound freshly painted under her stern windows. Given his captivity, Sam debated whether he should open a conversation with this captain, try to reach at least a minimal respect between them, and weighed that against his visceral disgust with him, his almost visual desire to see him swinging on a noose.

“She is a handsome enough vessel,” he ventured. “Twenty-two, by the look of her?”

Kington regarded him with some surprise. “You have a practiced eye, Mr. Lively. You have estimated her exactly.”

“At fourteen I was a midshipman in the Enterprise, twelve, and then a lieutenant in the Constitution, forty-four,” he stated quietly. “Some of that time we were in company with the John Adams, twenty-four, and your ship seems only the slightest degree smaller. And if you please, Captain, my name is Samuel Bandy, as you will discover upon a full investigation of the matter.”

Kington perceived exactly what Sam was doing. “We shall see. On my ship, I am addressed as ‘my lord,’ and you will oblige me by adopting the custom.”

Sam felt as though his jaw would break if he did so, but he swallowed his gorge and said, “Whatever you say, my lord.” Those two words, from the mouth of any American, sounded ridiculous.

As soon as they tied up, Kington scaled the boarding ladder first, and Sam followed, finding the captain already engaged with his second officer, a smallish, auburn-haired man with freckles, named Crawford. Once the Marines were up, a well-armed prize crew descended and pulled away. It took half an hour to make the exchange on the Althea, and the cutter returned with Evans and five of Sam’s crew who had determined to throw in with the English.

As soon as they came alongside, lines went tumbling down from the davits that curled out overhead. Crewmen made them fast to the eyebolts on the cutter’s bow and stern, and as soon as the last of the men stood on deck the cutter came up after them by jerks. Sam marked which of his men had turned coat and determined not to speak to them, even as he admitted to himself that they were not entirely beyond his sympathy. As the cutter was made secure in the davits Sam heard the orders barked and saw the yards braced up as they tacked and settled on a course east-nor’east, under full sail, close hauled but not straining, running full-and-by. Kington may be a miserable wretch, he thought, but he knew how to use the wind. Sam peered astern and saw his Althea following suit. At least, he thought, they were on their way to somewhere.

“Well, Lively.” It was Kington’s voice, and Sam turned to

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...