- Book info

- Sample

- Media

- Author updates

- Lists

Synopsis

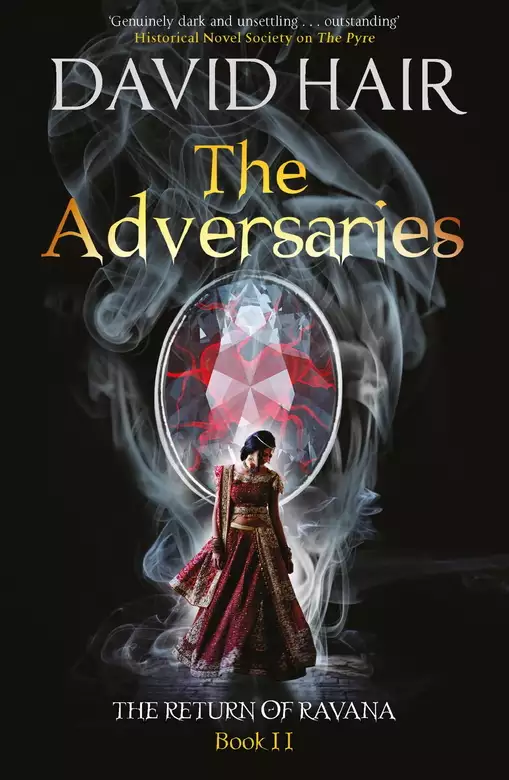

From the floodlit TV studios of Mumbai to the glittering Rajput courts, Vikram, Amanjit, Deepika and Ras must battle the sorcerer-king Ravindra: his power is growing, and so is his evil reach . . . The second in award-winning author David Hair's series The Return of Ravana. Mumbai, 2010 : Everyone's talking about Swayamvara Live!, the TV reality show recreating the ages-old custom where young men compete for the hand of a noble bride. In this case, the bride is Bollywood stunner Sunita Ashoka, who is pledged to marry the man who wins the on-screen contest. For Vikram Khandavani, it's a chance to draw out his nemesis Ravindra, the reincarnated sorcerer-king - but he's taking a deadly gamble. Delhi, 1175 : King Prithviraj Chauhan is about to storm the swayamvara of the beautiful Sanyogita - but he's not the only one fixated on the bride-to-be: Ravindra-Raj is coming too, and he's riding at the side of a fierce invader. Only Chand Bardai, in another life known as Aram Dhoop, the Poet of Mandore, stands between Ravindra and all the thrones of India. 'David Hair hasn't just broken the mould. He's completely shattered it' - Bibliosanctum on The Pyre

Release date: December 1, 2016

Publisher: Jo Fletcher Books

Print pages: 384

* BingeBooks earns revenue from qualifying purchases as an Amazon Associate as well as from other retail partners.

Reader buzz

Author updates

The Adversaries

David Hair

Fire, burning underwater, consuming flesh that is neither immortal nor wholly mortal.

Ravindra jerked back to consciousness to find the body he inhabited being consumed by a slow, intense tongue of flame, even though he was immersed in the underground stream. The water, frigid and slow, couldn’t numb the agony nor quench the fire smouldering in his flesh. In the pitch-black tunnel of water that tumbled him deeper into the darkness, the only visible thing was that growing ring of crimson.

He wrenched the arrow from his flesh, howling soundlessly, and as the last bubble of air left his lungs, they filled with water, a suffocating flood. At last the shaft burned out and was washed from his hand, but the fires in his flesh continued to burn, the pain so excruciating that he almost allowed himself to sink to the bottom and lie there until the disintegrating flesh shook his soul free. Then he remembered this body was just a cloak, one of dozens he’d worn over the centuries.

But to lose it meant weeks or months, maybe even years as a disembodied spirit, before he could find the right body and insinuate himself into his unwitting new host, and time was suddenly precious.

My Enemy is alive! Our thousand-year-old war has begun again and there can be no rest! He kicked out until his flailing feet found purchase on the stony riverbed and he pushed off, half swimming, half walking, tugged along by the currents of the underground stream. Finally, his head broke the surface. His clothing was burned away and his skin was seared black, this body charred past usefulness. His sword was gone and his five queens dissipated; they wouldn’t be able to re-form for months. He was utterly alone, and not even sure if there was any way out of this hidden warren beneath the Mehrangarh Fortress in Jodhpur.

But I am not dead yet . . . and what is death to me, anyway?

However deep his physical pain went, humiliation burned him deeper. Never before had his Enemy defeated him: Ravindra had always watched Aram Dhoop die, and not just the poet, but those others so intimately part of their centuries-old tale. Shastri! Darya! How many times had he killed them? How many more times would he have to destroy the three of them before he finally reincarnated as a god?

‘Aram Dhoop: I am not finished!’ he screamed at the blackness, the echoes mocking him, throbbing in the confined space. No one heard. Unbelievably, his enemies had got the better of him – this time. In all their many encounters, more than a dozen previous incarnations through the centuries, only once had the souls of Aram Dhoop and Madan Shastri come even close to defeating him. But this new encounter felt different: the girl Darya was here too, but this time, even the ghost of Padma was lurking. Everything was aligning: so many old faces returning, souls he had all but forgotten.

This life is to be the one! he told himself. This is the final life, the one that will unravel all the tangled skeins of those desperate days in ancient Mandore.

That thought goaded him, lending him energy and purpose, and he swam forward until the tunnel of water opened into a chamber of stone with a pocket of air below the surface – in the darkness he could just make out a small rocky bank ahead. In past lives he’d explored these caverns, but intriguingly, this was not a place he’d ever been before. Then his foot brushed against something that wasn’t stone. He reached down and gripped a stick . . . no, not a stick, a bone.

His head emerged from the water and he held up the bone, whispering a word to kindle in his other hand a faint purple-blue light that lit the chamber, making the roof a few feet above glisten. Even using this sliver of power threatened to rip his consciousness away – he quickly examined the bone, then looked around; more were scattered all about the chamber, washed up amidst other debris. There were cracks in the walls here, and the air was moving. In a surge of hope he rose from the stream.

As soon as it left the water, his shoulder burst into flame and he howled in agony and fury. Rage filled him, and shame, that Aram Dhoop could have lit this fire in his sacred flesh. He felt the touch of fear too: in this life, Aram had mastered the Agniyastra, the fire-arrow – how was that possible? And what else had he remembered?

He staggered and fell to his knees amidst the pile of bones. He knew at once that these must be the remains of Senapati Madan Shastri and Queen Darya. He rummaged among the bones, smashing these disintegrating sticks into pieces – until something moved, glittering, within the pile of detritus. He reached in and grasped a smoky crystal about the size of a baby’s fist and a thrill of recognition ameliorated the shattering pain for a second. It was a heart-stone, the one he himself had given to Darya back in old Mandore: a crystal that was intimately tied to her very being. He’d been searching for it through so many lives, and never before found it. His hand was shaking as he gripped it, his mind trying to reach past the pain to the possibilities . . .

This discovery could turn everything in his favour; he could use it to bring down his enemies – as he always had and always would – but this time he might finally unlock the clues and find a way to right everything that had gone wrong a thousand years ago.

Clutching the gem, he crawled back to the water and let the icy flow abate the burning of his body. There had to be a way out . . .

*

Almost six months later, as darkness fell over Rajasthan, a black Mercedes purred to a stop in the car park beneath the Mehrangarh Fortress. The lights of Jodhpur glittered below; the civic buildings and clock-tower glowed in the night. Traffic bustled, bells tolled, horns honked and birds squalled, the racket softened by distance. Two hard-faced men emerged from the front seats and peered about warily, then one opened the back door of the limousine and a tall, dark-skinned man got out.

He was an impressive figure, with curling black hair that fell past his collar and a flowing moustache. His Armani jacket was impeccably cut to conceal the handgun in a shoulder holster. Narrowed eyes pierced the gloom; he nodded curtly to the bodyguards and strode away across the steep, uneven terrain beneath the towering walls of the fortress. The bodyguards knew better than to follow him. His name was Shiv Bakli, though the Mumbai underworld knew him better as ‘The Cobra’.

Shiv Bakli now called himself a different name, an older one: Ravindra.

It took Ravindra several minutes to find the place: a tiny crevice in the slope barely large enough for a child to crawl through. He shuddered, remembering the superhuman effort it had taken to break out, pushing through with his shoulder ablaze and only minutes to live, and his hurried efforts to conceal his treasure before that body disintegrated into ash.

From within the crevice, he felt a cold regard: a snake had found the hole and made a home. He saluted it silently and walked a few paces down the slope. A dark smear on the rocks, barely discernible in the darkness, was all that remained of his previous body. He crouched beside a rock of distinctive shape and heaved it over, as he had that night.

He reached in a hand and felt something pulsing gently. He pulled it out and held it once again: the heart-stone of Queen Darya, a gleaming smoky crystal. He couldn’t resist sending a chill message of hatred and malice through it.

I am coming, little queen. There is nowhere you can hide.

*

Hundreds of miles away, in the kitchen in a block of apartments in Delhi, Deepika Choudhary felt a sudden debilitating tremor rip through her. The plates she was carrying crashed to the floor and she collapsed amidst the shards.

*

In his tiny Mumbai student dormitory, Vikram Khandavani heard his mobile ring as he stepped out of the shower. He wrapped a towel around his waist, examined the name and number on the display and answered. ‘Hey, Amanjit!’

‘Hey.’ Amanjit’s voice was taut with stress. ‘Vik, Dee’s in hospital.’

Vikram sank onto his bed, his legs going weak. ‘What?’

Amanjit hurriedly explained how his fiancée had collapsed in the kitchen. ‘Her folks have taken her to see the doctors. I’m minding the house, ’cos I’ve got to go to work shortly – they’ve called me already; she’s not in danger.’ He paused and then, his voice low, asked, ‘You don’t think it’s all beginning again, do you?’

‘Yeah. I think maybe it is.’ Vikram rubbed at his face tiredly. ‘Perhaps I shouldn’t go on this telly swayamvara thing after all?’

The line fell silent for a few seconds, then Amanjit said, ‘No, you should do it. If you’re right and this is tied to the Ramayana – and we know there’s a big swayamvara in that! – then we’ve got to see it through. We don’t have a choice, anyway – it’s all going to happen whatever we do. You’ve got to do it, Vik!’

The newspapers and television had been full of nothing else for months: Sunita Ashoka, Bollywood dream-queen, had decided to offer her hand in marriage to the winner of a game show based on the old-fashioned idea of the swayamvara: a contest between potential bridegrooms, like when the demi-god Rama won his bride Sita.

After what had happened in March, when they’d worked out their lives appeared to be echoing the old Vedic epic, Vikram had been especially wary of – and drawn to – such coincidences, so last week he’d joined millions of other young Indian men and sent off his application. Now he sighed. ‘Yeah, I know – I do think Sunita is important. I’m thinking she might be the reincarnation of one of Ravindra’s six queens – Padma, maybe. But what if it brings Ravindra down on us? We’re not ready!’

‘Then it’s on us to be ready, bhai,’ Amanjit said. ‘And don’t forget, Rama wins in the Ramayana! So all we have to do is follow the story and we’ll win too – I’m sure of it!’

‘I’ve told you before, I’m not Rama – and let’s not forget that in every other life I remember, Ravindra has won. In every one of them!’

‘Yeah, but how many have involved a swayamvara?’ Something chimed in the background and Amanjit cursed. ‘Damn, that’s the doorbell; gotta go. Think about it, Vik: in how many other lives have you been involved in a swayamvara?’ But he didn’t wait for an answer. ‘Bye!’

‘Yeah, bye. Love to Deepika. Bye!’ Vikram lay back, his wet body soaking the sheet, his mind far away, thinking about another time and another place, and how that swayamvara had turned out in the end . . .

Vishwamitra’s Gurukul, Rajputana, 1161

The bow sang, an arrow swished through the chamber, struck a wall and snapped before clattering to the floor. The young man in the centre of the shadowy chamber cursed, but the ancient man beside the door merely sighed. ‘Again, my prince,’ he said, in a dusty voice.

The archer bowed his head, nocked another arrow by touch – he had a cloth tied about his eyes – and half-drew the bow. The old man signalled to the only other person in the chamber, a small figure who padded from behind a pillar, hammer in hand. Dusty shafts of light pierced the gloom and refracted off the gongs hanging at the four points of the compass, each at a different height. At the signal from the old man, the small youth with the hammer reached out and chimed the northern gong, then darted behind the pillar. The arrows were round-tipped, but still dangerous at close range.

The archer’s arms flexed as he turned, drew and fired in one fluid motion. The arrow slammed into the gong, denting it as it chimed. The archer whooped joyously, wrenching off the blindfold. ‘A hit!’ he shouted, beaming expectantly. ‘I got it!’

The ancient one bowed. ‘You did indeed, my prince. A fine shot. Each day you strike the target more often.’

‘That was amazing, Prithvi,’ the youth with the gong-hammer exclaimed. ‘You’ll be the greatest known archer in the world.’ He was a skinny boy with a serious face and big, luminous eyes. His clothes, the prince’s hand-me-downs, were worn and ill-fitting, and his hardened hands were chapped and callused.

The young prince smiled triumphantly and his eyes strayed to the door where the light was growing fainter by the second. ‘The sun is going down, Guru-ji – and I’m starving! May I go?’

‘You may, my prince. You’ve worked hard today. But remember, you’re expected by the swordmaster at dawn tomorrow. No drinking tonight! No sore heads.’

Prithvi laughed. He was a big-boned youth with an open face, the beginnings of a moustache already showing on his upper lip. ‘Don’t worry about the drink, Guru-ji. I can handle it! Come on, Chand!’ he added to the smaller boy. ‘I’ll race you to our rooms!’

‘I’m afraid not,’ the guru said. ‘Chand must remain a while longer. I oversee his learning too, and unlike you, his progress is not so swift.’

The prince frowned at being thwarted, then leaned the bow and quiver against a pillar, draping the blindfold over them. ‘I’ll get us some food, Chand. Don’t be too long!’ He turned back to the guru. ‘I don’t know why you drill him so hard on weapons, Guru-ji. He’s only a poet.’

‘That’s for me to decide, my prince,’ the guru replied evenly. ‘Now run along.’

Once the slap of Prithvi’s sandals had faded into the distance, the guru turned to the smaller boy. ‘So, Chand, are you ready? Prepare!’

The slim youth draped the quiver about his shoulder, took up the bow, then allowed the old teacher to tie his blindfold. ‘Need I walk you into position?’ the old man asked.

Chand shook his head as he turned and strode unhesitatingly to the middle of the chamber. He nocked an arrow and went completely still. The old man paced about the room, once, twice, thrice, and then tapped the eastern gong. He didn’t bother to step behind a pillar.

Chand whirled towards the east. His lips fluttered as he released and the arrow ignited as it flew. It struck the gong and burst like a ball of fire, blackening the metal. A heartbeat later his second arrow flew towards the silent southern gong, hung a foot lower than the eastern one. It struck dead centre and remained stuck there, burning. The third sheared off one of the chains holding the western target so that it swung and struck a pillar with a crash. Despite that distraction, the fourth flew true, punching a fist-sized hole through the northern gong before exploding against the stone wall behind.

‘You’ve ruined another one,’ the guru remarked, eyeing the northern gong. ‘They don’t come free, you know,’ he added.

Chand pulled off his blindfold and glared at the western gong, hanging by the single chain. ‘I missed one again,’ he muttered. ‘I always miss one of the four.’

‘I’ve never heard of anyone like you, Chand. You are the finest master of shabd bhedi baan vidya I’ve ever taught. When it comes to the art of shooting blind you are kin to Rama, I swear. Perfection will come.’

‘Yes, Master, it will,’ Chand replied. ‘But I still don’t know why you won’t let me show my real ability. Why should Prithvi have all the praise when I am the more skilled?’

‘Because he is a prince, Chand. If you are to be his friend, then you may not exceed him in any matter, least of all one that is important to him. He tolerates you bettering him at poetry because he values it little. The arts of war are too dear to him. If you wish for his friendship, then you must not ever be seen to exceed him in such skills.’

‘But it just feeds his ego, Guru-ji – surely a prince should also know humility?’

‘In a perfect world, yes, but this world is imperfect. Princes become rajas, and rajas must be the acknowledged betters of their rivals, especially in battle. These are troubled times, Chand. The Rajput kings are always at war, and now the Mohammedans are flexing their muscles in the northwest. There will come a time when they will look this way and then we will need a great king, a true maharaja, to lead us against them. We will need Prithvi to be strong and unclouded by doubts.’

‘But how can I help him when he doesn’t know what I’m capable of?’

‘By using your skills in secret, and being his loyal friend. Let him be the greatest known archer in the world – you will be the greatest unknown one. The hidden weapon is oft times more dangerous than the visible one.’ The guru cupped the boy’s chin and lifted his face. ‘Are you his loyal friend, Chand?’

‘Of course, Guru-ji. I am loyal to Prithvi for ever.’

He answered with such fervour that the ancient teacher could not help but smile. ‘Then put aside your complaint. You will gain enough recognition, I’m sure. Let the whole world know that the friendship of Chand Rathod of Kannauj and Prithvi Chauhan of Ajmer is as strong a bond as that between Rama and Lakshmana and people will remember your names for ever: surely that is fame enough?’

*

The ashram was called Gurukul, and the princes and courtiers of the Chauhamanas, greatest of the royal dynasties of the Rajput tribes, had been coming here for generations to learn at the feet of its legendary teachers. All the vital skills of the warrior-prince were taught here: war and weapons, the equally deadly ways of politics, and the skills of art and literature. Prince Prithvi Chauhan was the third and youngest son of Someshwar Chauhan, lord of the Chauhamanas clan, King of Ajmer and Dilli. No successor had yet been named, but Prithvi was already seen as the prince with the greatest promise. His prowess could secure his succession – and in this world where kin fought tooth and claw for thrones, a lack thereof could cost him his life. Though he was only twelve, he was big for his age and could not only out-wrestle and out-fence all the other young men in the ashram, he was also acknowledged as the greatest archer of them all.

All except for – though he didn’t know it – his best friend Chand.

Chand was a distant cousin, the poor son of a poor branch of the Rathod family, of the rival Gahadavalas clan. Chand was barely eligible to attend the Gurukul, and then only as a scholar – he was far too small to be a warrior. But Prithvi, perhaps because there was no rivalry between them, had befriended the skinny boy and protected him, and they were soon spending all their free time together. Prithvi was generous, and though quick-tempered and impetuous, he was swift to forgive and forget. They learned together, laughed together, minded each other’s backs against jealous rivals and false friends, and forged a bond even closer than brothers, for in the courts of Rajputana, brothers were often deadly rivals. And it was never forgotten that Prithvi led and Chand followed.

They had been together at the Gurukul for six years; their time there was coming to an end.

On his last night, Chand was taken to the temple at the heart of the Gurukul. It wasn’t a grand place made of white marble and glittering gold, nor did it bustle with worshippers like the temples in the town below the ashram. It was very, very old, and in truth, rather dingy, the smell of decay never quite masked by the incense.

Watching Guru-ji walk away, Chand found himself filled with trepidation. His final test, if that was what it was, was to keep vigil all night and experience what visions and dreams might come. The previous night had been Prithvi’s turn – he’d claimed to have seen a vision of himself as maharaja, but afterwards he’d confessed to Chand that he’d fallen asleep and had no such dream at all. He’d been amused by the whole thing.

Nothing supernatural would dare happen to Prithvi, Chand thought, but I’ve always had strange dreams . . . He wasn’t nervous because he was afraid of visions, though: what he feared was the morning, when he and Prithvi would go to Ajmer. The warband had arrived that week to escort the prince home to his father’s court – and Chand was to learn at the feet of Jindas, the court poet. Guru-ji had warned them of courtly intrigues that would test their friendship to the limits and they’d sworn loyalty to each other, over and again, a multitude of oaths and promises. But he was still afraid.

He began his vigil sitting cross-legged in front of the shrine in the circular inner sanctum, which was barely ten yards across. There were three idols, which had been painted with ochre so often the features could barely be discerned. Shiva was on Chand’s left: god of death and rebirth, lord of dance, a guide for one who searched. To Chand’s right was the image of Vishnu, the law-bringer, protector and warrior, mankind’s champion. ‘All men find their balance between these two,’ Guru-ji had told them, ‘between the extremes of passion and calm. Seek your own balancing point, venerate both and live in harmony.’ Prithvi always tended towards Shiva, so Guru-ji made him spend more time meditating upon Vishnu. Chand, drawn to Vishnu, was commanded to think often on Shiva.

Before him, halfway between the two male gods, was Durga, the female force: she who rides the tiger, who tends, protects and intercedes, she who bears and nurtures the child. ‘She divides them, but she also draws them together,’ Guru-ji had told them. ‘Do not underestimate the women of the court. They have it in them to make you whole – or to rip you apart.’

Chand didn’t really understand that; he hadn’t seen a woman since he came here as a child. He shivered slightly at the fierce expression on Durga’s face.

Prithvi liked to make jokes about girls these days. He would be married soon, no doubt, to some princess of Rajputana. Chand too would be given a bride when he went to court, which wasn’t something he was looking forward to.

The early hours of his vigil were measured in the slow crawl of moonlight across the walls and floor of the shrine. The full moon was riding towards its zenith; soon it would light where he waited. That was the time when the visions would come, Guru-ji had said, if they came at all. As he waited, breathing in the faint residue of incense and the damp coldness of the night air, feeling the chill creep into his skin, an ache in his back and joints made him feel like an old man. His breath steamed and he closed his eyes. Far away in the valley, birds squabbled, disturbed in their perches by some night thing. A bell tinkled, cattle lowed and went quiet. He drifted.

Something exhaled in his face. He jerked awake, and found himself still in the temple, cross-legged in the moonlight, alone.

Not alone.

A young woman sat opposite him, her hair tangled, her eyes tawny and wild. Her clothes were ragged and she smelled – no, she stank – of sweat and musk. Her irises were shaped like crescent moons and her nails were long. Her frigid breath sent a chill through him.

He could see the statue of Durga through her body.

He stopped breathing as she reached out, slowly, inexorably, and touched the middle of his forehead. ‘Wake up, Chand Rathod.’ Her voice was like a snake’s. He jerked backwards and sprawled on his back, twitching, utterly terrified. Then she was upon him, her body pressing his down with the weight of an avalanche. He opened his mouth to scream but nothing came. Her hands gripped his temples and icy knives stabbed into his head. The ground was falling away as images flooded his mind. He spun, her eyes boring into his, filling his sight, until they were all and everything—

The visions began, but they weren’t visions at all . . . they were memories . . .

. . . of him, reciting poems to a dreadful king, trembling, knowing one slip would mean his end . . . a tall, muscular captain clasping his shoulder . . . a young woman in a torn gown with a bow in her hands . . . a queen screaming as flames engulfed her while a lush beauty standing beside her laughed in glee as she too burned. Then darkness . . .

. . . as a peasant, Bhagwan, scrabbling for life in a dreadfully poor village, watching as a troop of mercenaries ride through, shoving captives before them. Their leader turns and glares at him with his one eye, and a whip snakes out. He howls in pain . . .

. . . which becomes a mourning cry as he is another man, chanting the death-prayers of a girl who was meant to have been his wife, though she died before he ever met her. He reaches out to her dead face curiously . . .

. . . and she opens her eyes, only it isn’t her, it’s a tangle-haired madwoman who follows him through the streets of a city, calling a name that isn’t his, yet is. When he turns to confront her she’s gone, and thugs with cudgels and knives close in. A blade flashes . . . He gasps, clutching his chest . . .

There was worse, and over and over again, and throughout it all, one face presided: one set of eyes, one being. His Enemy.

Ravindra.

The next morning Chand wondered why he had been so scared of such mundane things as court intrigues and petty politics, when there was so much more in the world to fear.

*

Guru-ji woke him as sunlight crept across the shrine. ‘Chand – Chand, wake up!’ Then more gently, ‘You’re safe, now. You’re safe.’

Chand ignored his old master. He knew that he would never be safe again.

‘They were visions of past lives,’ he told Guru-ji later. He was lying on a low bed and the old man was squatting at his side, his lined face drawn with worry. Chand’s vision had left him feverish and ill; he’d been lying there for two hours now, still shaking, semi-delirious. His bedclothes were damp and stinking of sweat, his own, and that of the ghostly woman from his visions – he could not purge her animal reek from his nostrils, no matter how he tried.

‘How can you know that, Chand? Perhaps they were just delusions, brought on by exhaustion and cold? They probably meant nothing.’ The old man didn’t sound certain. Chand had never heard uncertainty in Guru-ji’s voice before.

‘Past lives,’ he repeated. ‘I know this.’

‘Then who is this “Ravindra”? I don’t know the name.’

‘He was a king, in Mandore, maybe three hundred years ago . . . and then he was a mercenary captain who flayed me to death sixty years later. And a century later, a thug who beat and mutilated me. He is my Enemy. In my last life, he rode me down on a battlefield. I escaped him in Mandore, but he has destroyed me in my three subsequent lives and he is out there somewhere, waiting for me again. I know this.’ He gripped his teacher’s arm. ‘He can’t die!’

Guru-ji’s face held none of the comprehension that Chand desperately wanted to see. He thinks I’m raving . . .

‘I’m worried for you, Chand,’ the teacher said. ‘Perhaps you shouldn’t travel today. Go to Ajmer when you’re feeling better – perhaps we can explore these visions of yours? Your friendship with Prithvi will survive a small parting, but in your present state, you may not survive the road.’

‘No! I must be with him – I have to protect him!’

‘You’re in no fit shape to protect anyone, my friend. I’m sure all these soldiers the king has sent will be enough, if the prince needs any protection at all.’

‘But you don’t understand, Ravindra is also Prithvi’s Enemy – he has slain him as well, in other lives! I have to be with him, to protect him!’

‘You’re sick, Chand. You’re not yourself right now.’

‘I am going with them,’ Chand insisted, his voice strangely resonant and mature. ‘We’re bonded together, through debts that transcend the grave.’ The ancient teacher could only stare as Chand rose on shaky legs. ‘Our lives are at stake, Guru-ji – all of our lives – and I have to be with him, or it will all happen again.. . .

We hope you are enjoying the book so far. To continue reading...